Monday Feb 16, 2026

Monday Feb 16, 2026

Friday, 7 September 2018 00:00 - - {{hitsCtrl.values.hits}}

By Jennifer Langston

By Jennifer Langston

Scientists with the Elephant Listening Project estimate that Africa’s population of forest elephants has dropped from roughly 100,000 animals in 2011 to fewer than 40,000 animals today. But those numbers are largely based on indirect evidence: ivory seizures, signs of poaching and labour-intensive surveys that are too expensive to be done regularly.

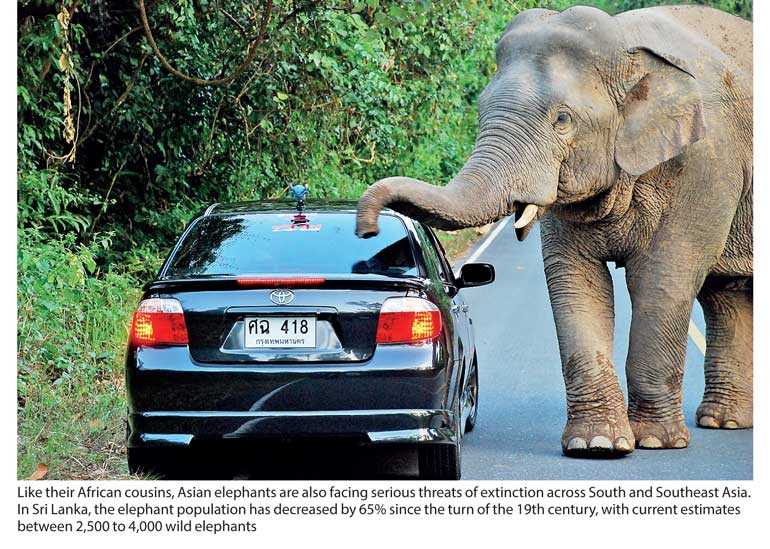

Like their African cousins, Asian elephants are also facing serious threats of extinction across South and Southeast Asia. In Sri Lanka, the elephant population has decreased by 65% since the turn of the 19th century—with current estimates between 2,500 to 4,000 wild elephants1. The problem is compounded by the animal’s preference for crops such as sugar cane, bananas and other fruits frequently grown in the region; and the large blocks of forests being cleared for human settlements and expanding agriculture, instigating the human-elephant conflict.

But conservation groups along with authorities in several countries are working to create a future for elephants in landscapes that are dominated by humans and rapid economic development. They are investing in anti-poaching operations, reducing impacts on elephant populations, preventing further habitat loss and, most importantly, lowering local animosity against elephants. They also have a powerful new tool at their disposal: artificial intelligence.

‘What have you found?’

Deep in the rainforest in a northern corner of the Republic of Congo, some of the most sophisticated monitoring of animal sounds on earth is taking place. Acoustic sensors are collecting large amounts of data around the clock for the Elephant Listening Project.

These sensors capture the soundscape in Nouabalé-Ndoki National Park and adjacent logging areas: chimpanzees, gorillas, forest buffalo, endangered African grey parrots, fruit hitting the ground, blood-sucking insects, chainsaws, engines, human voices, gunshots. But researchers and local land managers who placed them there are listening for one sound in particular — the calls of elusive forest elephants.

Conservation Metrics, a Microsoft AI for Earth grantee based in Santa Cruz, California, uses machine learning to monitor wildlife and evaluate conservation efforts. It is applying its sophisticated algorithms to help the Elephant Listening Project, based at Cornell University’s Lab of Ornithology, distinguish between forest elephant calls and the other sounds in a noisy tropical rainforest.

Researchers use the elephant call data to build more accurate and frequent population estimates, track their movements, provide better security and potentially to identify individual animals, which can’t be easily seen from the air. It’s also the perfect job for AI—looking for these rare patterns in terabytes of data that would take humans years.

It is one of many ways biologists, conservation groups and Microsoft data scientists are enlisting artificial intelligence to prevent the illegal killing of elephants across Africa, stop the global trade in their parts and preserve critical habitat.

But there has been a bottleneck in getting data out of these remote African forests and analysing information quickly, says Peter Wrege, a senior research associate at Cornell who directs the Elephant Listening Project.

“Right now, when we come out of the field with our data, the managers of these protected areas are asking right away, ‘What have you found? Are there fewer elephants? Is there a crisis we need to address immediately?’ And sometimes it takes me months and months before I can give them an answer,” says Wrege. Conservation Metrics began collaborating with the Elephant Listening Project in 2017 to help boost that efficiency. Its machine learning algorithms have been able to identify elephant calls more accurately and will hopefully begin to shortcut the need for human review. But the volume of data from the acoustic monitors is taxing the company’s local servers and computational capacity.

In response, Microsoft’s AI for Earth program has given a two-year grant to Conservation Metrics to build a cloud-based workflow in Microsoft Azure for analysing and processing wildlife metrics. It has also donated Azure computing resources to the Elephant Listening Project to support its data-processing costs for the project.

‘We’ve only

scratched the surface’

Across the continent in East Africa, Jake Wall, a research scientist with Save the Elephants who collaborates with the Mara Elephant Project and other conservation groups, typically has more immediate access to data about the savannah elephants he studies in Kenya and seven other countries. That’s because animals in those populations have been outfitted with GPS tracking collars that transmit location data via satellites and cell networks.

Even with advances in radio collar technology, sensors and imagery collection, a lot of additional work is needed to turn that data into scientific insights or actionable intelligence, says Wall.

“I think we’ve only scratched the surface of what’s possible,” says Wall. “We’re really excited because the expertise that Microsoft and AI for Earth can bring to the table includes skillsets that field biologists don’t typically have.”

Wall has been collaborating with Dan Morris, a Microsoft researcher working with AI for Earth, on a half dozen project ideas. One examines how to use machine learning to identify streaking behaviours — when elephants run fast and in an unusually straight line — that can be a sign of poaching or other threats.

Morris has also been working to apply machine learning algorithms to camera traps, which are remote field cameras that are triggered by motion and photograph anything that crosses their path. But finding an animal of interest can be like looking for a needle in a haystack.

“The potential for machine learning to rapidly accelerate that progress is huge. Right now there is some really solid work being done by computer scientists in this space, and I would guess that we’re less than a year away from having a tool that biologists can actually use,” says Morris.

Wall and Morris are also beginning to work on using AI to distinguish between elephants and other animals like buffalo or giraffes in aerial photography. Knowing when and where elephants are coming into contact with other wildlife — and particularly domesticated animals like cattle — can help rangers minimise conflicts with humans and help scientists better understand disease vectors.

These insights can also inform land-management decisions, such as where to lobby for protected areas and where to locate human infrastructure like roads and pipelines. That’s one of the most significant yet least understood threats to elephant survival, says Wall. With access to the right imagery data, AI tools could help begin to keep tabs on, and draw useful insights into, human encroachment into their habitat.

(The writer is a public information officer and journalist who has covered fast-moving developments in technology, higher education and public policy.)

Footnotes

1“Sri Lankan Elephant.” WWF, World Wildlife Fund, www.worldwildlife.org/species/sri-lankan-elephant.