Monday Feb 23, 2026

Monday Feb 23, 2026

Saturday, 4 June 2022 00:00 - - {{hitsCtrl.values.hits}}

By Helani Galpaya

The need for cash transfer to ease the inflationary burden faced by Sri Lankans has never been higher. While the monthly amounts paid by the Government are paltry, it will at least provide minor relief to those who need it the most. Therefore, it is welcome news that the World Bank has repurposed previously committed funds to pay for cash transfers.

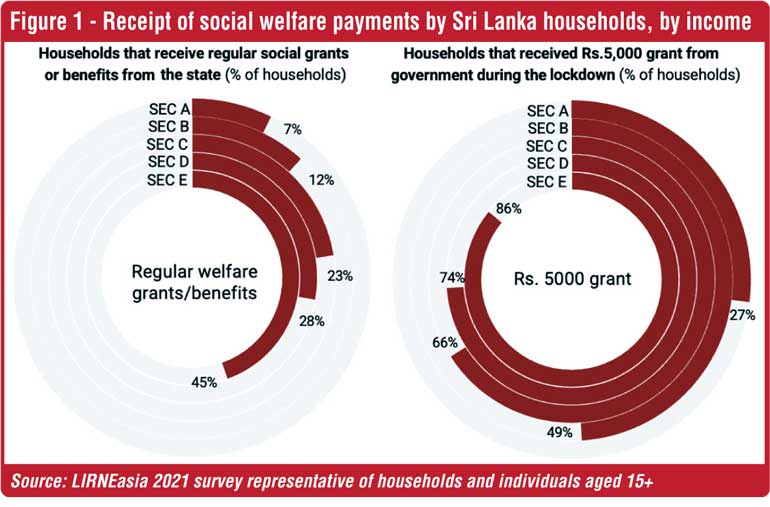

It appears that families or individuals who are already recipient will be getting these payments funded by the World Bank. But what has been long known and has been confirmed again in 2021 research by LIRNEasia is that many poorest families that should get payments don’t receive them, while some families who are not poor get payments that are meant to be based on low income. As shown in the graph on the left, high- and middle-income families (in Socio Economic Classification or SEC A, B and C) receive payments while many poorest families (in SEC D and E) don’t. This targeting problem is worse when we look at data related to the payment of Rs. 5,000 made during COVID lockdowns.

Another parallel funding stream from the World Bank promises to improve the payment system by bringing together multiple databases, linking payments to the proposed digital ID number, and conducting surveys to identify poor better. However, the current method (and the 2019 proposals to update the 2002 Welfare Benefits Act) of identifying poor households is based on finding a set of easy-to-measure variables (such as asset ownership and education level) because there is close correlation between such ownership and actual income. This method of proxy means testing (PMT) works in the long run because asset ownership tends to be reflective of income levels over time. It is easier than trying to identify actual income or expenditure in a country with high informal income and low tax records/base.

However, PMT is exactly what it is – a proxy for real income. It is possible that people have high asset wealth, but very low or no income due to job losses (think tourism sector). PMT is a measure of past wealth, as reflected in ownership of a house, fishing boat, etc. and not of current income. The measurement depends on a survey that documents household level variables. These surveys are not cheap and have to be done quite frequently in order to not miss those who fall below the specified poverty line (or move out of it) in between surveys. While a method for people to self-register as ‘newly poor’ can be implemented, it’s unlikely people will de-register when they move above the poverty threshold.

Research from other countries clearly demonstrates that new forms of data can be used to understand and predict income at household and individual level. The digital data trace left when people use their mobile phones is one such data stream. In combination with survey data, Google night lights and other data such as call detail records from telecom operators are better proxy for income. It’s cheaper to continually analyse how people’s income change once initial systems are set up and therefore doesn’t suffer from the problem of infrequent and expensive surveys as a data source. It is less distortionary than going to houses to identify household assets which could incentivise underconsumption of assets. It’s an equitable data source, with 97% of households having access to mobile phones.

Recipients would have to agree to reveal their mobile number, mechanisms to preserve their privacy (such as implementing data minimisation policies and technical approaches such as federating learning, having independent data analytics team that doesn’t share data with government) would need to be implemented, and gaps in individual mobile phone access (such as a roughly 10% gap in male vs. female access to phones, and the 3% of households without access to a phone as of 2021) would need to be looked into. But the resulting targeting would be better.

Better targeting would lead to better utilisation of funds by using the money for those who need it the most and enabling some people from the long waiting list of Samurdhi to become beneficiaries. More importantly, transferring their payments to banks and then enabling them to cash out their payments at the network of mobile top-up locations and bank ATMs would mean people travel far less distance to access their cash. The existing mobile cash out locations and participating bank ATM networks would enable households in the poorest income decile to access cash by travelling an average of 5.1 km compared to the 8.3 km that travel on average today to a Samurdhi bank. It’s important to get cash relief to Sri Lankans now. But equally important to reform our cash out and targeting mechanisms using new data, new technology and new thinking.