Monday Feb 23, 2026

Monday Feb 23, 2026

Friday, 16 November 2018 00:00 - - {{hitsCtrl.values.hits}}

Tax evasion – in all sizes, shapes, and forms – is a reality that exists in Sri Lanka. It has been cited as one of the many reasons for the declining tax-to-GDP ratio that the country has experienced since the 1990s. The Central Bank has called for “close monitoring of high end transactions to fight widespread tax evasion that has led to a fall in direct tax revenue” in its Annual Report for 2017.

Although tax evasion by individuals and corporates has been recognised as a burning issue, especially in the context of Sri Lanka trying to increase its direct tax take, there is little empirical work on tax evasion for policymakers to make evidence-based decisions when setting tax rates. This is mostly due to limitations in the data.

However, a starting point for measuring tax evasion is to consider ‘border tax evasion’, since export and import data is well recorded for the country, and can act as a source of measuring evasion that could be taking place at its border.

Underreporting and mislabelling of imports

Two types of import tax evasion could be taking place in Sri Lanka: underreporting of imports and mislabelling of imports. By using the discrepancy between double declarations of the same trade flow (for example: Sri Lanka’s import of good X from China, as reported in Sri Lanka’s books, and China’s export of good X to Sri Lanka, as reported in China’s books is a double declaration of the same trade flow), it can be discerned whether underreporting and/or mislabelling of imports might be taking place at the border.

Underreporting refers to under invoicing the true value/quantity of an import in order to evade taxes. Mislabelling refers to falsely labelling an import as a ‘similar’ import of a lower-taxed variety. As a hypothetical example, chickens and turkeys are similar goods which are different varieties of ‘poultry’ and they may have different tax rates. There might be an incentive to mislabel a chicken as a turkey, if a turkey has a much lower tax rate slapped on it.

Presence of border tax evasion: Are we calling chickens, turkeys?

A recent study on ‘Tax Rates and Tax Evasion: An Empirical Investigation of Border Tax Evasion in Sri Lanka’ examined border tax evasion under the above mentioned framework. The study found that evasion of both varieties – underreporting and mislabelling – took place at Sri Lanka’s border, for imports from the country’s top seven import partners, in 2014.

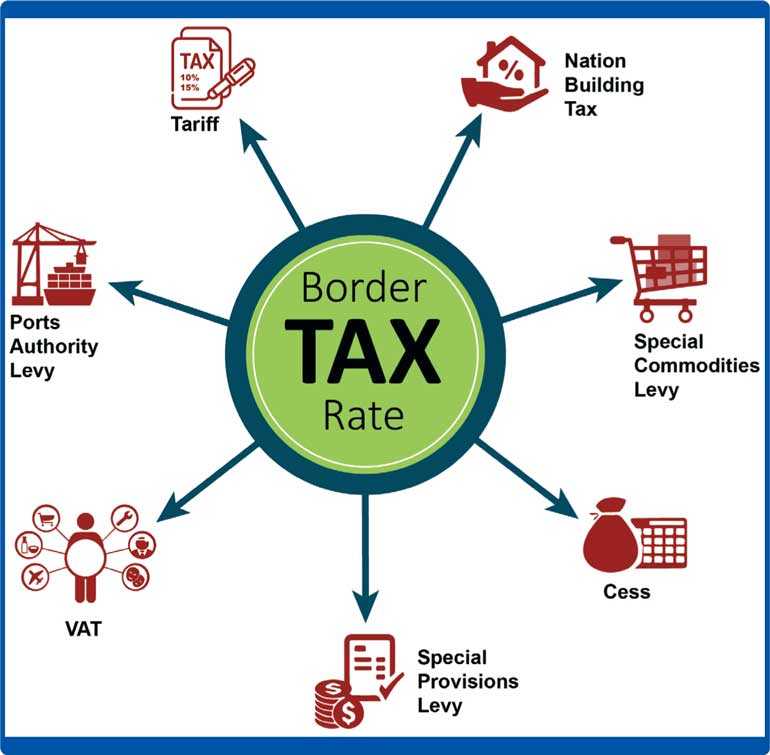

The results take into consideration the evasion of the full import tax schedule, since Sri Lanka has a gamut of taxes slapped on imports, apart from the general/preferential tariff rate – VAT, Ports Authority Levy (PAL), Nation Building Tax (NBT), Special Commodities Levy (SCL), Cess, and Special Provisions Levy (SPL).

The study found that with every percentage point increase in the border tax rate, evasion would increase by 1.7%. This positive relationship between tax rates and tax evasion implies that underreporting of imports might be taking place. Further, with every percentage point increase in the minimum tax rate among a group of similar products (such as say, poultry) evasion was found to decrease by 2.1%.

Hence, this negative relationship implies that lower the tax rate on similar varieties, higher are the occurrences of mislabelling higher-taxed varieties as lower-taxed varieties. Relating to the previous example of ‘poultry’ – if chickens are the higher-taxed variety and turkeys are the lower-taxed variety, there is an incentive to mislabel chickens as turkeys.

Furthermore, the study found that much of the identified evasion is taking place for goods imported from China. This can be attributed to the type of goods in Sri Lanka’s import basket from China, relative to the other import partners considered.

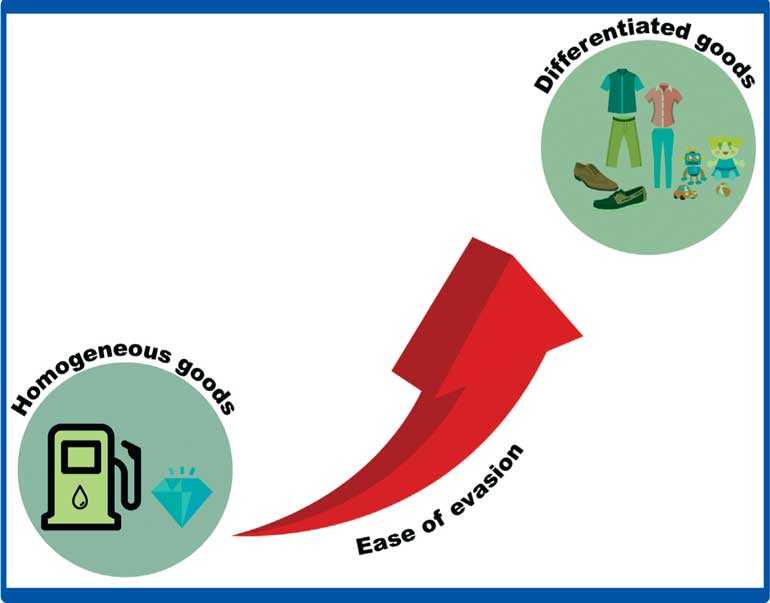

More ‘differentiated goods’ are imported from China, rather than ‘homogeneous’ goods. Homogeneous goods are those that have a well-known reference price (e.g. petroleum, diamonds) and are therefore more difficult to evade. Differentiated goods on the other hand, do not have reference prices (e.g. clothes, shoes) and are therefore easier to evade. Hence, the study revealed that the extent of evasion differs with the ease of evasion, which in turn depends on the nature of the product being imported.

Policy implications

From the policy perspective of a country trying to increase its tax take, the presence of border tax evasion is not good news for Sri Lanka. Although the Government is focusing on restructuring the tax system towards more direct means of taxation, higher revenue generation from existing levels of border taxation is still possible, if no evasion took place.

It is possible that evasion at the border is driven by frequently changing border tax policy, which allows for more opportunities to evade taxes. Tax reforms are subject to frequent amendments – for instance, several changes took place during the research period between 2014 and 2016, including a hike in VAT rates, several changes to the PAL, NBT, and frequent amendments to SCL and SPL for given products. These changes are not effectively documented, and lead to confusion among importers and customs officials alike, or provide more opportunity for officials to be discretionary.

For instance, a case study of regulatory procedures found that decisions on granting certain import tax exemptions in Sri Lanka are subject to undue official discretion. Verbal directives are given by officials on eligibility for an exemption, rather than following a documented and consistent process. This type of regulatory inefficiency leaves plenty of room for tax evasion to take place. In addition, Sri Lanka’s border tax schedule is complex, with combinations of up to eight different taxes being applied on imports. This complexity undoubtedly adds to inefficiency and confusion at the border, which might provide more opportunities for evasion.

Therefore, simplifying and streamlining the border tax schedule by eliminating para-tariffs, minimising ad hoc changes to tax code, and having all revisions to the tax code well documented by approval granting agencies, is the need of the hour. Efforts which are currently underway to establish a National Single Window for trade might help to reduce space for evasion at the border, through paperless trade facilitation.

(The blog is based on the study ‘Tax Rates and Tax Evasion: An Empirical Investigation of Border Tax Evasion in Sri Lanka,’ published in the South Asia Journal of Economics, Volume 19 Issue 2, September 2018, available at: http://journals.sagepub.com/doi/abs/10.1177/1391561418794690)

[Harini Weerasekera is a Research Officer at the Institute of Policy Studies of Sri Lanka (IPS). To talk to the author, email [email protected]. To view this article online and to share your comments, visit the IPS Blog ‘Talking Economics’ - http://www.ips.lk/talkingeconomics/]