Saturday Feb 21, 2026

Saturday Feb 21, 2026

Friday, 15 June 2018 00:00 - - {{hitsCtrl.values.hits}}

By Marwaan Macan-Markar, Asia regional correspondent

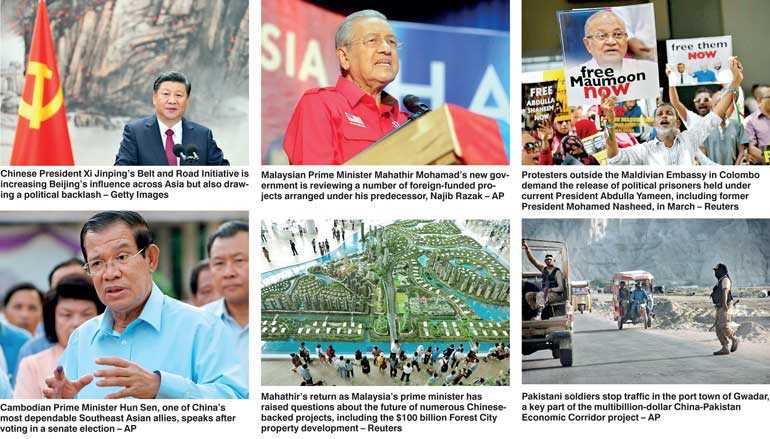

Kuala Lumpur/Colombo (asia.nikkei.com): As he campaigned ahead of last month’s Malaysian general election, Mahathir Mohamad, the veteran politician, deftly tapped into resentment of Chinese investments in his country to build support. It is an increasingly familiar strategy across Asia: From Cambodia to Pakistan to the Maldives, all of which are headed for national elections this year, opposition forces are using Chinese-funded ventures to draw blood from incumbent governments.

For Mahathir, the investments were an easy target. The nonagenarian, now back for his second stint as prime minster after leading the opposition alliance to a shock victory, had plenty of opportunities to play the China card.

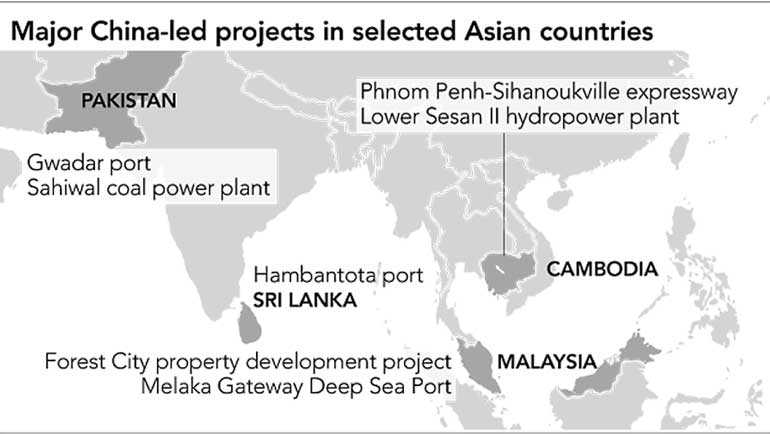

In Kuantan, the largest city on Peninsular Malaysia’s eastern coast, he lamented China’s expanding economic footprint. In his sights was the first joint Malaysia-China industrial park, located in the city, where Chinese contractors are also building a stretch of a $ 14 billion, 668km rail link.

“This is part of our country that has been handed over to foreigners,” Mahathir said at a rally, before a crowd of about 20,000. “If we have more industrial parks like this ... we will have less land of our own in Malaysia, our lands will be owned by foreigners.”

Much like the leader Mahathir defeated, Najib Razak, Cambodian Prime Minister Hun Sen and Maldivian President Abdulla Yameen are taking flak for their embrace of heavy Chinese investment and increasingly autocratic tendencies.

From Paris, where he has exiled himself, Cambodia’s hounded opposition leader Sam Rainsy took umbrage at China’s dominating economic presence. “What Hun Sen is doing is in order for China to help protect his power,” the former president of the Cambodia National Rescue Party, the main opposition group that was dissolved with a controversial court ruling, told a gathering of supporters in April. “Chinese are allowed to freely enter Cambodia, to take land, islands, beaches and mines.”

That speech, posted on Rainsy’s Facebook page, has resonated among the opposition ranks in Cambodia.

Opposition figures in the Maldives are just as bitter. With talk of a presidential election in the air – the first round is likely to be held in September – they blast Chinese “rip-off infrastructure projects” in their rallying cries against Yameen. The three largest Chinese-funded projects in the country are worth $ 1.5 billion, which is “more than 40% of the Maldivian GDP (gross domestic product),” according to Gateway House, an Indian international affairs think tank.

“Many of these Chinese megaprojects are merely licenses for President Yameen and his cronies to steal hundreds of millions of dollars,” Ahmed Naseem, a former Maldivian foreign minister, told the Nikkei Asian Review. “The Chinese look the other way to this theft, because they want the Maldives to borrow [and fall into debt], enabling China to demand land in compensation.”

In much larger Pakistan, where the geopolitical stakes are higher, leaders of the opposition Pakistan People’s Party have their work cut out for them in the run-up to parliamentary elections in July. The ambitious China-Pakistan Economic Corridor, where Beijing plans to invest more than $60 billion, is in their crosshairs. The blueprint includes roads, railways, power plants and multipurpose pipelines for oil and gas, along with the development of Gwadar port.

The incumbent government is promoting the corridor for two reasons: the depth of Pakistan’s ties with China, and the chance to become a pillar of Beijing’s Belt and Road Initiative. But according to Taj Haider, a senior PPP leader, the program is sure to be a focus on the campaign trail.

“Contestants for the parliament need to understand the full scale of this project,” Haider told Nikkei. He expects the PPP election campaign to press the government for “full information” on the corridor, launched five years ago.

This rising political tide across Asia has put Chinese diplomats on notice, said a veteran foreign ministry official of a South Asian country. He said it reflects growing anxiety among local populations about Chinese infrastructure projects steamrolling through their countries, with little discussion about the environmental and social costs.

More and more, he noted, the projects are being questioned in the mainstream media and on social networks.

For Chinese diplomats accustomed to a certain way of doing things, the sea change poses a real challenge. “The Beijing political and foreign policy establishment, by tradition, tends to focus exclusively on the official line of authority and inherently neglects to recognise that actual power resides with people,” said Patrick Mendis, a Chinese international affairs scholar at Harvard University.

This stems from the mindset that accompanies China’s one-party system, he added. China does not have a “clear answer to deal with the sort of messiness in democratic governance.”

Already, China has faced two setbacks stemming from Asian elections. The latest example is Malaysia, where Najib’s government was seen as a reliable partner worth propping up with large infusions of Chinese cash. Investments included the $100 billion Forest City property development, the $ 14 billion East Coast Rail Line, the $ 10 billion Melaka port project and the $ 900 million Kuantan port expansion, among others.

Now some of these plans are up in the air, with Mahathir calling for a review of foreign-funded infrastructure projects. This is in keeping with a campaign promise his Pakatan Harapan (Alliance of Hope) coalition made before vanquishing Najib.

The Chinese received an earlier lesson in Sri Lanka in January 2015. They had cultivated then-President Mahinda Rajapaksa – another leader with autocratic leanings – only to see him suffer a shock defeat at the presidential polls. By then, China had poured billions of dollars into Sri Lanka for infrastructure projects ranging from a deep-sea port, an airport and highways to an artificial island on the coast of Colombo, the capital.

On the eve of that game-changing poll, executives tied to Chinese infrastructure projects openly canvassed for Rajapaksa at evening receptions for the captains of commerce and finance, a commercial banking source revealed.

Three of the projects, including the $ 1.5 billion Hambantota port, were located in Rajapaksa’s fiefdom in the southern district of Hambantota. During the campaign, the opposition targeted Rajapaksa for agreeing to Chinese-funded endeavours paid for with commercial loans that drove Sri Lanka’s beleaguered economy deeper into foreign debt.

That debt meant China’s setback in Sri Lanka was only temporary. Having inherited at least $ 8 billion in obligations to China, the new government was forced to kowtow to Beijing. According to an international development expert, this led to Sri Lanka in effect forfeiting its sovereignty over the Hambantota port for the next century.

The government handed a Chinese company a 99-year lease in exchange for $ 1.12 billion to put toward debt repayment. Such a twist appears unlikely in Cambodia. Hun Sen, in power for the last 33 years, is muscling his way toward a win at the polls on 29 July. The 65-year-old leader, whom the Chinese have cultivated as their most dependable ally in mainland Southeast Asia, is not shy about his connections with Beijing.

“Some people questioned why there are so many Chinese?” he said in a speech marking the launch of a Chinese-funded road project in May. “There are numerous [Chinese] investment projects, so how could there be no Chinese?”

Cambodia is no Chinese underling, he argued, insisting the countries “maintain a status of equal partnership and footing.”

The partnership is built on Belt and Road projects earmarked for Cambodia, including new hydropower facilities, road improvements, upgrades to the deep-water port in Sihanoukville and telecom network enhancements, among others. Chinese loans and investments in Cambodia stood at $ 5 billion at the end of 2017. Billions more are on the way after Chinese Prime Minister Li Keqiang signed 19 agreements for additional infrastructure projects early this year.

Not surprisingly, China’s rapid march through terrain once dominated by Western governments and pro-Western financial institutions, like the World Bank, has triggered a flurry of critical reports. They warn that China’s economic inroads into Asia amount to “debtbook diplomacy” or, worse, predatory lending.

Reports by the US State Department and the Center for Global Development, a Washington think tank, have named countries like Cambodia, the Maldives, Pakistan and Sri Lanka as being ripe for Chinese interference in domestic politics due to ballooning infrastructure debt.

Still, China appears undaunted. It is rapidly adjusting to the political heat, one Southeast Asian diplomat said.

“Their diplomacy has become more sophisticated and multi-layered,” he told Nikkei. “They are starting to engage with as wide a segment of stakeholders as possible, including the political opposition, media and civil society in some countries.”

The charm offensive includes flying opposition leaders, journalists and civil activists to Beijing and other cities to build trust, the diplomat added.

In tightly contested polls, though, China is also showing its determination to use “sharp power,” as Mendis described it, to help political allies. He said Chinese political and business leaders are realising that “the realities of political campaigns in democracies would demand money to gain power,” and are reaching into their deep pockets.

“The Chinese are strategically and brilliantly exercising their ‘sharp power’ in these political processes to advance their national and economic interests,” Mendis said.

The upcoming elections in Pakistan, Cambodia and the Maldives may serve to measure China’s success in that regard. And as Chinese diplomats in these countries step out to tout the job-creation power of the multibillion-dollar investments, there is little doubt that Beijing’s money remains on the incumbents.

(C.K. Tan in Kuala Lumpur and Farhan Bokhari in Islamabad contributed to this report.)

(Source: https://asia.nikkei.com/Spotlight/Asia-Insight/China-emerges-as-wild-card-in-elections-across-Asia)