Saturday Feb 21, 2026

Saturday Feb 21, 2026

Wednesday, 5 December 2018 00:00 - - {{hitsCtrl.values.hits}}

The objectives of food and nutrition security in Sri Lanka are yet to be achieved, and there is a gap in polices and strategies focussed on achieving food security. While the problem of food insecurity is increasingly agricultural, current food security policies lack an explicitly agricultural focus, leaving food systems with no mandate to address food insecurity.

Among the most significant reasons for increasing food insecurity and malnutrition is climate change. Climate change without adaptation can potentially affect farm livelihood and all aspects of food security, including food access, utilisation, and price stability. It is evident that both long-term, gradual changes, such as rising temperature and erratic rainfall patterns, as well as extreme climate conditions such as severe droughts and floods, are taking place in Sri Lanka’s climate. These changes threaten agricultural production, make those who are dependent on agriculture more vulnerable, and exacerbate the risks of food security.

While agriculture in Sri Lanka has evolved in close harmony with the prevailing climatic conditions of the country, it has been made evident during recent decades that the traditional farming experiences and accumulated knowledge on weather patterns have become less useful in the process of agricultural decision making. The climate in the country has undergone a change to such an extent that the expected rainfall does not come at the correct time of the growing season, thus putting farmers in extreme difficulty.

Climate change impact on food security

Domestic food availability in Sri Lanka is dependent on local production and imports of food crops, livestock products and fish. Domestic agriculture provides more than 85% of the food requirement. Sri Lanka is nearly self-sufficient in rice, the staple diet item of Sri Lankans. The local production of other main food sources – that include vegetables, root crops, and fruits – exceed 75% of total availability.

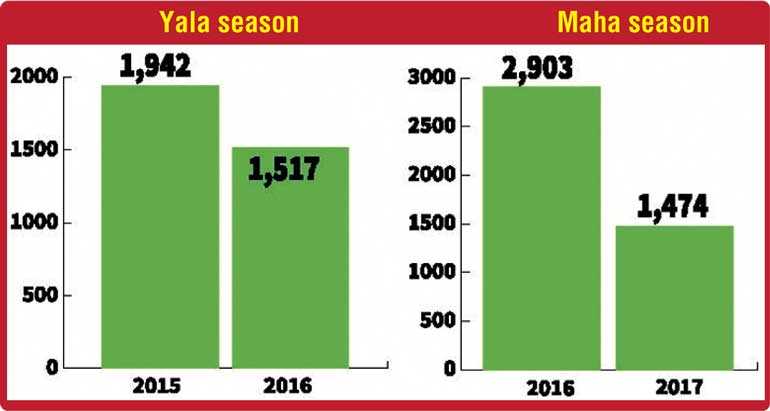

Gradual changes in climatic conditions have already affected the production of domestic crops, including Sri Lanka’s staple food rice, and extreme climate events threaten to worsen this. At the beginning of 2016, Sri Lanka faced the worst drought in 40 years, severely affecting the agricultural production in the country. This situation was further exacerbated by severe floods in mid-2017 in the south-western parts of Sri Lanka. The impact of continuing dry spells and severe floods was disastrous for the country’s food production.

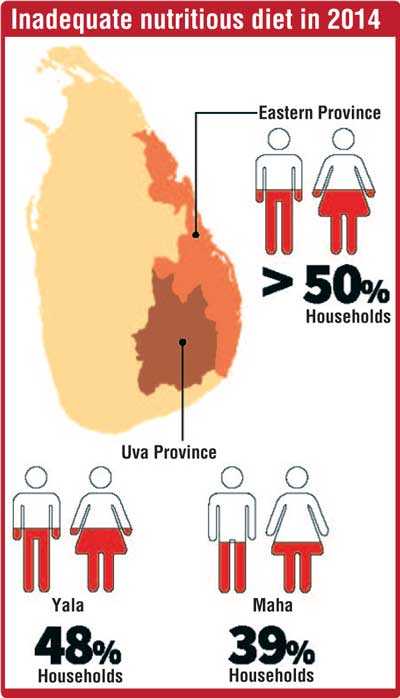

Diminished agriculture production and income as well as higher food prices due to climate change have affected the access to food by households. Research have found that more than 50% of households in the Eastern Province of Sri Lanka could not afford an adequately nutritious diet in 2014, while this has gone up to 48% in the Uva Province. Also, the Food Price Index (FPI) has increased by a staggering 22% from 104.3 in 2014 to 127.5 in 2017, compared to a 10% increase in the Non Food Price Index (NFPI) during the same period.

Stability and climate resilience

Whether the country is producing enough food for its future is a serious challenge due to the constantly rising national requirement, owing to population growth and the growth of real per capita income. Climate change affects both the food supply stability and food consumption stability. The least resilient groups are the poor households in the north, tea estates and south-eastern parts of the country due to frequent storms and cyclones, very limited livelihood diversity and high sensitivity of their income source to climate variability respectively. Thus, improving climate resilience for farmers to manage the shocks with no long-lasting adverse effects is very important to achieve the stability aspect of food security.

Way forward

Climate-smart agriculture (CSA) is an approach that transforms agricultural systems to effectively support farming livelihoods and ensure food security in the current context. CSA can prevent the worst impacts of climate change on farm livelihoods, and help make people less vulnerable to food insecurity and poverty. CSA highlights that climate threats can be reduced by increasing the adaptive capacity of farmers, as well as by increasing the resilience and efficiency of resource use in agricultural production systems.

While reducing the agriculture sector’s contribution to climate change is less of a priority for Sri Lanka, more importantly, farming communities need to adjust their livelihood patterns to sustainably increase their production and income. This demonstrates that the solutions for climate risks and food insecurity can be derived from making agriculture climate smart.

Sri Lanka is off to a good start when it comes to making agriculture climate smart. The Government has developed a National Adaptation Plan to help adapt to climate change. The National Agriculture Policy, undertaken by the Ministry of Agriculture includes climate change adaptation as a main priority. While different CSA strategies including developing tolerant varieties, promoting water efficient farming methods, and adjusting cropping calendars according to climate forecasts have been proposed, Sri Lanka is still behind in terms of developing systems for timely issuing and communication of climate related information to farmers.

Moreover, even though resilience is embedded in traditional knowledge, none of the policy responses to climate change support and enhance indigenous resilience. Therefore, CSA practices should be tailored to the specific characteristics of the local farming systems and local socio-economic conditions, and require a well-articulated information management system coupled with improved small holder access to finances, resources and markets.

(This Policy Insight is based on a chapter written by IPS Research Fellow, Manoj Thibbotuwawa.)