Tuesday Feb 17, 2026

Tuesday Feb 17, 2026

Saturday, 23 May 2020 00:01 - - {{hitsCtrl.values.hits}}

Violence against women tends to increase especially during times of crisis. Self or household isolation has become our new normal amidst the COVID-19 pandemic. The consequential economic turmoil and strict measures to counteract the spread of the virus have left countless people increasingly dependent on public services and authorities to fulfil their most basic needs. This increased dependency on authorities to provide essential services could find more women, especially those in conflict affected areas to be particularly isolated and thus more vulnerable to sexual bribery.

In the article published on 24 January, Centre for Equality and Justice (CEJ) Founder and Executive Director Shyamala Gomez and Senior Project Coordinator Ando Anthappan shared an overview of sexual bribery in Sri Lanka. This week, we follow up on the issue and discuss its impact and how you can help yourself or another victim survivor to navigate this issue. Following are excerpts:

Q: In the first interview published you defined what sexual bribery was. Could you give us a brief recap of what it is and why this issue is rarely discussed?

A: Sexual bribery can be described as an ‘improper benefit’ that is sexual in nature, demanded from a person in a position of power in exchange for a service or a favour.

In 2015, a woman activist we were working with informed us about bribery of a sexual nature taking place in war affected areas. There was a lack of terminology to describe the issue, making it a vague concept for many. We called it ‘sexual bribery’ and began researching and documenting these cases.

An example of these types of cases would be when 33-year-old Ambiga*; a single working mother and Samurdhi beneficiary met with the Grama Niladhari to enquire as to why she hadn’t received the allowance she was entitled to; she didn’t expect what came next. “He asked me if I would give him something special”. Without her daily income to support her three small children and dependency on the allowance to buy the daily essentials, Ambiga found herself in a helpless position.

Q: Why is it that most cases of sexual bribery go unreported?

A: Sexual bribery occurs for several reasons. As we mentioned in the first interview, we work with women affected by war and poverty. Unlike their urban and cosmopolitan counterparts, they might not take action due to the desperate circumstances they are faced with, especially during times of crises where the availability of essential items are tightly controlled as a protective measure. They may come from conservative backgrounds which inhibit their social interactions. Thus, such situations leave them feeling embarrassed or ashamed, resulting in them denying themselves the public services that they need and are entitled to.

In times of crisis, there could be instances where some officials take advantage of the economic and other restrictions that accompany the controlled supply of essential services. There could be instances where they might misuse their powers to satisfy personal gratifications at the expense of a woman’s dependence on their office to provide the essential goods and services she needs.

Q: What is the resulting impact such an incident leaves on a victim survivor?

A: Most situations take place over a period of time during which the alleged offender builds a relationship of trust with the target of his advances. When a sudden attack takes place then, it causes guilt, shock and confusion on the part of the victim survivor. This is intensified especially because the offender is at times someone from their community/background. “I had thought that he would be respectful to the abaya that I wear” is what Sherooza* from Puttalam told us with regard to her attacker who was a member of her own community.

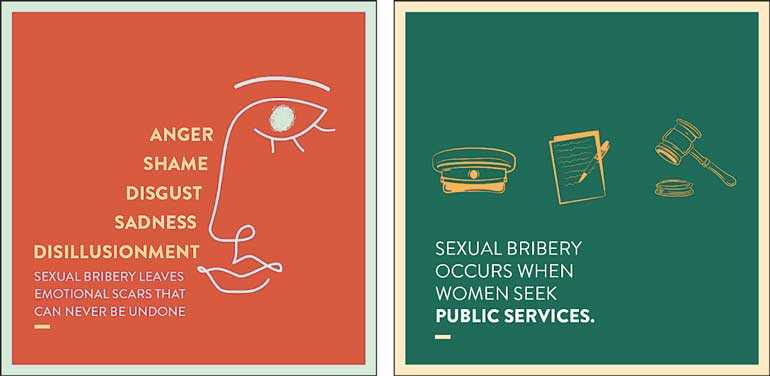

Incidents are not necessarily limited to physical harassment. They can be verbal, taking the form of persistent texts or WhatsApp messages with demands of a sexual nature, phone calls or requests to meet the perpetrator alone in order to obtain the essential goods or services required. Such incidents are followed by feelings of disgust, shame, sadness, anger and disillusionment. In some cases the mental and emotional turmoil translates into physiological and psychological stress.

Sujatha, a mother of three* remembers vomiting soon after a distressing appointment with a local government official. Grace, a 27-year-old widow* from Vavuniya stated that she had frequent nightmares of being raped by the man who had asked her for a sexual favour. The act can create a long term disturbance in a victim survivor’s daily life. In one incident, a woman didn’t leave her house for an entire year and had trouble eating.

Offences such as these create a ripple effect. In addition to the physical and psychological trauma is the social stigma that ironically follows the victim survivor, extending the distress and suffering to their families. CEJ’s research, found that those who had made complaints had the support of male family members while those who did not have such support feared the mere exposure of the issue.

It is not uncommon for the harasser to continue their torment or even take revenge on those who report the offence. “When it happened to me, I was unsure as to whether I wanted to report the incident because I feared for the safety of my children,” shared a 30-year-old single mother from Batticaloa. A similar sentiment was shared by another mother from Trincomalee. “Especially when they are girl children, we worry about the shame that would fall on our daughters if the incident becomes public,” she added.

Q: What is the course of action one can take when such a situation arises?

A: In reality, most individuals lack a full understanding of their legal rights and entitlements and feel powerless in situations where a figure of authority preys on this lack of awareness when demanding a sexual favour.

It is important that a woman has somebody to talk to at the initial stage, be it an activist at the grassroots level, a women’s society in the village like Lanka Mahila Samithi or even a trusted friend, relative or neighbour. In a report published by CEJ in 2018 with 10 Muslim women from the Eastern, North Western, and North Central Provinces we found that only three women had lodged complaints – one woman had lodged a complaint with the OIC (Officer in Charge) and the Women’s Desk at the police station, another had lodged a complaint with the OIC, a women’s group and the Human Rights Commission, while a third woman had lodged a complaint with the international donor of the NGO where she worked.

This was also the first time most of them had spoken about it to an outsider. Even then, some women felt embarrassed to reveal all the details of the distressing situations they had faced. It is thus important that they have a familiar or comfortable figure to confide in at the initial stage.

Action against sexual bribery can be taken through the Commission to Investigate Allegations of Bribery or Corruption (CIABOC). Individuals can lodge a complaint either by calling them on their hotline – 1954 or through their website. Although sexual bribery also falls within the mandate of the Human Rights Commission and the Public Service Commission, it is unclear what type of support can be envisaged if a complaint is made to these institutions.

Q: How can someone help a victim survivor of sexual bribery?

A: The reaction of society and community has a significant impact on the abused party. From the beginning, their support or judgment can affect someone’s decision to move forward with a complaint or silence them. “When I told my husband about what happened he ended up beating me because he assumed that I had encouraged the perpetrator,” was what one woman told us. The support of a community, family or even a few trustworthy people has a significant impact on the individual during and once the case is over.

Even a simple gesture such as listening, offering well-informed advice, encouragement and even helping to circumvent the sexual predator’s power can be a tremendous support to anyone who has or is the target of such an act. In a research study on sexual bribery among Female Heads of Households in the Northern Province conducted by CEJ, six out of 25 women shared their stories for the very first time.

“Although we were initially reluctant to do so, we feel relief,” they shared. After this discussion, two of them even wanted to monitor the accused and collect evidence to get him punished. A supportive environment not only nurtures the confidence of the party, but also builds a platform that empowers other women who have undergone sexual bribery to come forward.

If you or someone you know has been subjected to a form of sexual bribery contact the following:

1) For assistance or to lodge a complaint – Commission to Investigate Allegations of Bribery or Corruption (CIABOC)

2) Free counselling services – Sri Lanka Sumithrayo

3) Free legal support – Women in Need

References

*Names have been changed to protect privacy. Based on real events.