Tuesday Feb 24, 2026

Tuesday Feb 24, 2026

Tuesday, 15 May 2018 00:00 - - {{hitsCtrl.values.hits}}

The high cost of securing employment abroad is a barrier to cross-border labour mobility for low-skilled workers in developing countries. Migration cost is distributed among many stakeholders in the migration value chain (VC). This Policy Insight highlights the main findings of the study ‘Cost of Low-Skilled Migration to Saudi Arabia, South Korea and Malaysia: Value Chain Analysis – Sri Lanka’. The study utilises VC framework to map the migration process and cost for low-skilled workers from Sri Lanka (LKA) to Saudi Arabia (SAU), South Korea (KOR), and Malaysia (MAS), with a view towards identifying leverage points in the chain for policy intervention to reduce migration costs.

These three corridors are selected due to their unique importance in the LKA migration scenario. SAU is the leading destination for low skilled migrant workers from LKA and recruitment to SAU from LKA is governed by private-to-private arrangements between recruitment agents in the two countries. In comparison, KOR is a leading non-Middle Eastern destination of Sri Lankan workers, where the entire recruitment process is carried out by governments, involving bilateral agreements, and bypassing private recruiters. The choice of MAS is based on the growing opportunities in that country for Sri Lankan workers and the evolving recruitment networks in the corridor.

For SAU, the scope of the study is limited to female domestic workers (FDW), because they account for nearly half of Sri Lankan workers heading for SAU. For MAS and KOR, the study focuses on low-skilled workers in the manufacturing sector, given the significance of these occupations for Sri Lankan migrant workers in these countries. The study adopts a qualitative methodology and collected data through Key Informant Interviews and Focus Group Discussions in Sri Lanka.

Findings

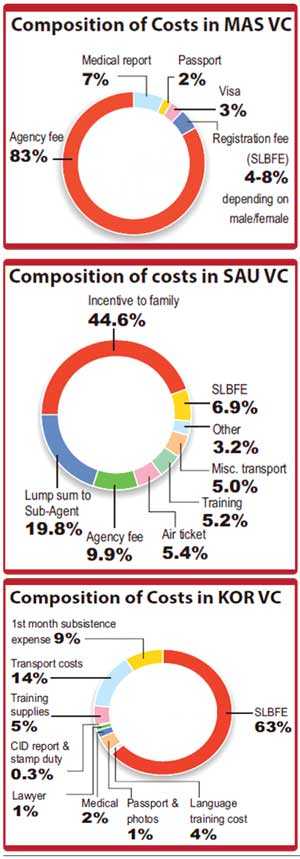

SAU VC

By mapping the VC to SAU, the study identifies employers, recruitment agents in SAU and LKA, Sri Lanka Bureau of Foreign Employment (SLBFE), sub-agents, and migrants as the key players, while Saudi Arabian Embassy in LKA, Sri Lankan Embassy in SAU, financial institutions, medical centres, Grama Sevaka (GS) officers, District Officers (DOs) and migrants’ families are other players. The analysis of the VC finds that migration to SAU is a private-to-private recruitment arrangement. The total cost of approximately $4,750 (Rs. 500,000) is financed by the employer in SAU and the migrants do not bear any upfront cost. This cost consists of incentives to the migrant’s family, commissions to agents and sub-agents, administrative and regulatory fees to SLBFE, and cost of fulfilling the documentary requirements/ amassing credentials.

When lump sum payments to the migrant’s family and sub-agent are excluded, the subtotal is $902 (Rs. 129,882), out of which 47% goes as payments to the SLBFE. The contract period of a housemaid in SAU is generally 2 years, and they receive a monthly salary of about $243 (SAR 1,000). In the SAU VC, when involved, the most powerful player is the sub- agent, who is an informal entity operating at grass root level to mediate between the licensed agent and the prospective migrant in LKA. The sub-agent also assists the potential migrant to navigate the migration process. The bargaining power of sub-agents allows them to shop around different agencies and demand higher commissions for his services, while they are also criticised for engaging in malpractices leading to exploitative and abusive situations of migrants.

KOR VC

Under the Employment Permit System (EPS), the government-to-government labour migration arrangement between LKA and KOR is a relatively streamlined process with fewer key players, namely, HRD (a public recruitment agency within the Ministry of Employment and Labour [MOEL] which supports foreign workforce employment under the EPS system), SLBFE, and migrants. Other players include immigration authorities in the two countries, Korean Embassy in LKA, financial institutions, medical centres, language training instructors, Criminal Investigation Division (CID), lawyers, and migrant’s family. The more streamlined process contributes to keep recruitment costs low at approximately $1,389 (Rs. 200,000). Here the entire recruitment and migration cost is borne by the migrant and 63% is paid out to the SLBFE. However, due to the involvement of Korean language training requirements, the wait time to migrate to KOR is longer than that of SAU, while a work contract to KOR is three years and the monthly salary ranges from $694 - 868 (Rs. 100,000-125,000).

MAS VC

The VC for the recruitment of low-skilled manufacturing workers to MAS consists of key players such as employers, recruitment agents in LKA, KDN (Kementerian Dalam Negeri) - the Ministry of Home Affairs in MAS, SLBFE, and migrants. Recruitment agents in LKA play a significant mediation role between employees and employers, and have close links with the final employers in MAS. Other players in the VC include immigration authorities in the two countries, the Malaysian Embassy in LKA, and medical centres in LKA. Unlike in the case of the SAU VC, the involvement of sub-agents in LKA and recruitment agents in MAS is not extensive in the recruitment process.

The migrant’s cost of securing employment in MAS is approximately $1,041 (Rs. 150,000). Moreover, due to the agents’ significant involvement in the recruitment process and its related preparatory work, here the agent bears an additional cost of nearly $3,472 (Rs. 500,000) for ground work in preparation for recruitment. Given that these costs are applicable to recruiting a batch of migrant workers, the per-migrant cost declines when large numbers are migrants are recruited through the given agent. The contract period for a low-skilled worker to MAS is generally three years and the monthly wage is in the range of $206- 275 (MYR 900-MYR 1,200).

Policy Recommendations

To lower migration cost, the study suggests the following:

This Policy Insight is based on findings from a study on ‘Cost of Low-Skilled Migration to Saudi Arabia, South Korea and Malaysia: Value Chain Analysis – Sri Lanka’ by Bilesha Weeraratne, Janaka Wijayasiri and Suwendrani Jayaratne. Contact [email protected] or [email protected] for more information.