Saturday Feb 07, 2026

Saturday Feb 07, 2026

Friday, 5 July 2019 00:01 - - {{hitsCtrl.values.hits}}

By Shanika Sriyananda

She had no option left but to flee her village to escape them, those who started storming into her house to collect due instalments of the loan she had taken some months ago. Scared and ashamed, she sought refuge at her elder sister’s house, located a fair distance from her village in Mullaitivu, until she could collect some money to repay a portion of the debt, including the accumulated interest of several months.

Kandasami Sivamma (name changed), 57, became entrapped in debt after she had obtained credit from a microfinance company to send her son abroad, through an agent who was smuggling people to Australia. Their dreams were shattered when he was arrested and sent back home, just a few weeks after his departure from the northern shores.

When she delayed paying the loan instalments and interest for several months, the debt collectors started coming home, but she had no means of paying the loan. Without proper employment, her son, who promised to repay the loan and the interest once he was settled in Australia, is also struggling to repay the loan. In debt up to her eyeballs, there is no more gold jewellery left to pawn as she lost all of it to a pawn shop nearby a few years ago. Sick with a heart ailment, Sivamma’s husband’s meagre earnings are not enough to pay even the monthly instalment of the loan.

Sivamma is not alone when it comes to paying back microfinance debt. Several women from three districts – Monaragala, Batticaloa and Mullaitivu – were interviewed for a research on microfinance debt, which found that women were trapped in debt and facing several issues at home and in their villages while suffering psychologically.

Microfinance, according to the Central Bank of Sri Lanka, is defined as ‘the provision of financial services to low-income people’. This system, which has a long history in Sri Lanka, was introduced as an effective concept to empower rural women by giving them loans to start livelihood projects to overcome poverty.

However, due to the absence of background checks and monitoring, borrowers have inadvertently led women to borrow money for reasons other than income generation activities. In many instances, they have obtained loans for consumption purposes. This practice has also resulted in an inability to repay the loans, less savings and assets and discontent within the family and community.

The research highlighted the impact on the family, including children, due to microfinance practices. Children of these families wanted their mothers to stop obtaining loans in fear of MFI officers coming to their houses without prior notice to collect the interest, serious arguments between debt collectors and parents, and other women in the community ill-treating their mothers due to inability to repay the loans. One female borrower from Monaragala had said that when she was planning to apply for a loan, her nine-year-old son pleaded with her not to apply as she and her husband had conflicts over paying previous loan instalments

Women compelled to borrow

It was found that women are compelled to borrow to finance health emergencies, funerals, coming-of-age ceremonies and weddings through microcredit facilities.

Two female borrowers, in Monaragala and Mullaitivu, said that they took loans to meet the health expenses of their husbands.

“When my husband was sick, the hospital here could not help so he was sent to the Badulla hospital. We had a lot of money problems. We had to go to Badulla every day, so for these expenses I took a loan of Rs. 40,000,” the female borrower in Monaragala said.

“I borrowed many loans because my husband is suffering from kidney disease and I have spent Rs. 700,000 for his treatment,” the female in Mullaitivu, who took several loans, said.

Another female in Monaragala, who has used the microfinance facility to take many loans, said that some women in her area receive loans for cultivation purposes but she obtained loans to meet other household expenses.

“When we spend loans for other things, again we take another loan. When my mother died, I took Rs. 100,000 each from two institutes. I told them it was for cultivation. Because the officer could not give the money immediately, I borrowed from a lender in the village until the loan came through. For my daughter’s concert, we had to pay Rs. 10,000. I have to meet the expenses of my three children. When my husband met with an accident, I borrowed about Rs. 200,000 and for my mother’s almsgiving, I borrowed Rs. 150,000. I am now in debt to nearly Rs. 700,000,” she said.

Most women and their families engage in agriculture and have little or no access to formal employment opportunities that would offer them stable income sources.

Socio-economic issues

The research titled ‘Debt at My Doorstep: Microfinance Practices and Effects on Women in Sri Lanka’ carried out by the Centre for Poverty Analysis (CEPA), which is an independent Sri Lankan think-tank promoting a better understanding of poverty-related development issues, authored by Chandima Arambepola and Kulasabanathan Romeshun, was released recently.

It has found that unregulated and unsupervised microfinance and credit process have attributed to many socio-economic issues among rural women in Sri Lanka.

With the proliferation of Microfinance Institutes (MFIs) in Sri Lanka, CEPA has carried out this research specifically focusing on the practices adopted by the MFIs in micro-lending and their effects on the female borrowers.

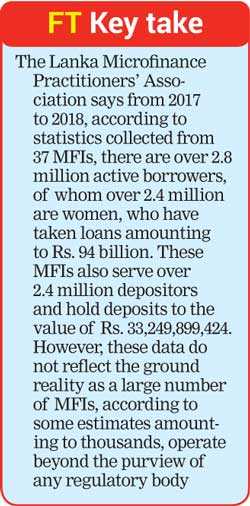

According to the Lanka Microfinance Practitioners’ Association (LMFPA), data gathered from 37 MFIs for from 2017 to 2018 shows that there are over 2.8 million active borrowers, of whom over 2.4 million are women, who have taken loans amounting to Rs. 94 billion. These MFIs also serve over 2.4 million depositors and hold deposits to the value of Rs. 33,249,899,424.

However, these data do not reflect the ground reality as a large number of MFIs, by some estimates amounting to thousands, operate beyond the purview of any regulatory body.

The report states that the expansion of the microfinance sector as a possible lender has simultaneously given rise to concerns about mounting debt and the inability of poor women, specifically those living in the north and east, to repay their credit.

The report states that lack of monitoring, commitment of MFIs loan officers to have follow-up visits and the availability of some livelihood activities that can be used as means to access loans have created a situation that makes women more indebted to MFIs as they take multiple loans, not for livelihood activities but to meet other expenses.

Microfinance loans for consumption

“They give the loan for livelihood development, but we use the loan for other purposes. I showed tailoring and cattle rearing as reasons for getting the loan,” said a female from Batticaloa, while another from Monaragala said that she took the loan saying it was for cattle rearing.

“I showed someone else’s cattle as my own since I don’t have my own. That is how people borrow. We show different means to borrow money,” she said.

“Where women do borrow for a livelihood opportunity, it is also to support the spouse’s livelihood rather than one’s own. But on a few occasions where women seek financing for a livelihood of their choice, rarely do they embark on pursuing new livelihood options. The women engage in small-scale enterprises, mostly to do with cultivation or running small retail shops in the community,” CEPA’s Senior Researcher Chandima Arambepola said.

She said that women in Mullaitivu, a former war-torn area in the north, get loans to help their husbands and sons to migrate, and have to shoulder the responsibility of repaying the debt, as the earnings of their husbands and sons as low-skilled workers is not sufficient to pay the loan instalments.

“Although such instances can be seen as a form of investment, especially because of the anticipated higher financial returns through wages earned in a foreign currency, not all migration trajectories are successful. When men return prematurely, due to different reasons, women are saddled with loans to pay off in the absence of the promised foreign remittances,” she explained.

The research has also found that none of the women who obtained loans from MFIs have established their businesses or expanded their existing business outside their community or village.

“The multiple reasons cited by women for borrowing microcredit helps raise a pertinent question: to what degree are the lenders aware of the multiple reasons behind women’s borrowing habits? Women work within the system by providing ‘proof’ of some livelihood option to satisfy the documentation that the MFI requires, but how is it that such unchecked lending can take place within a small local community?” the report states.Arambepola said that micro-credit-induced indebtedness was not the focus of the study but when they were looking at the issues related to livelihood and the community mediation boards, indebtedness came up as an issue as a result of microfinance.

Strong nexus between indebtedness pushing women

“When I was doing my research on women migrating as domestic workers to Middle Eastern countries, we saw a strong nexus between indebtedness pushing women, which was not very apparent before, to migrating to pay their debts that have been happened as a result of micro-credit,” she said, spelling out some of the issues that women are facing when obtaining and repaying MFIs’ loans.

Meanwhile, women losing their saving habits, facing family issues and losing unity among other women in their villages top the list of issues that they are confronted with due to microfinance practices implemented to empower the rural female population.

Highly indebted with multiple microfinance loans, women are increasingly under threat of losing easily-liquefiable assets, mainly gold jewellery, to settle loans. “I pawned jewellery at the banks and the Chetty shop for school fees and loan purposes. I couldn’t get it back,” a woman in Mullaitivu was quoted saying in the research.Arambepola said that tensions had been created between Government officials like Grama Niladharis (GN) and the officials of the District Secretariat (DS) as the immediate mediators of their respective villages, when they attempted to resolve issues related to micro lending.

“They are becoming equally frustrated because they have no control when women come to them with their problems, ranging from the presence of male officials to debt-related suicides.

“They are becoming equally frustrated because they have no control when women come to them with their problems, ranging from the presence of male officials to debt-related suicides.

The GNs and DS level field officers tried to discourage people from taking loans from private MFIs by setting up offices in communities, but it was not successful. This has led to more tension between the prospective borrowers and the GNs and DS officers,” she said.

It was found that women are compelled to borrow to finance health emergencies, funerals, coming-of-age ceremonies and weddings through microcredit facilities. “They give the loan for livelihood development, but we use the loan for other purposes. I showed tailoring and cattle rearing as reasons for getting the loan,” said a female from Batticaloa, while another from Monaragala said that she took the loan saying it was for cattle rearing. “I showed someone else’s cattle as my own since I don’t have my own. That is how people borrow. We show different means to borrow money,” she said

Children victims of microfinance

The research also highlighted the impact on the family, including children, due to microfinance practices. Children of these families wanted their mothers to stop obtaining loans in fear of MFI officers coming to their houses without prior notice to collect the interest, serious arguments between debt collectors and parents, and other women in the community ill-treating their mothers due to inability to repay the loans.One female borrower from Monaragala had said that when she was planning to apply for a loan, her nine-year-old son pleaded with her not to apply as she and her husband had conflicts over paying previous loan instalments.

Sanasa Development Bank Chairperson Samadani Kiriwandeniya said that it was unfortunate for Sri Lanka to talk about indebtedness among women in 2019 as Sri Lanka had lost the opportunity to learn from the mistakes of microfinance process and micro-credit from the Bangladesh experience since 1996.“Until 2011, according to several reports, we had an effective microfinance package to address rural indebtedness. However, due to a single system of microfinance, which was brought from elsewhere without considering some of the solid systems available in the country, we ended up with high indebtedness in the peripheries,” she said, adding that due to that alien system, certain elements in the economy were profiting from the vulnerability of a large population in Sri Lanka, especially women.Development Facilitators Ltd. Consultant Anura Atapattu, explaining how regulations on microfinance could contribute to indebtedness among women, stressed on the need for regulating all lending institutions and establishing a micro-credit regulatory framework.Despite the many socio-economic issues they face as a result of being trapped in debt, these women say that they will continue to obtain loans from MFIs, mainly to overcome their day-to-day issues and not to invest in livelihood projects. In the backdrop of their desperation, it is imperative for the Government to step in and regulate and strengthen the microfinance sector to make it more effective to empower rural women instead of trapping them in inescapable debt.

Pix by Shehan Gunasekara