Wednesday Feb 18, 2026

Wednesday Feb 18, 2026

Tuesday, 19 December 2017 00:21 - - {{hitsCtrl.values.hits}}

Article to mark International Migrants Day on 18 December 2017

By Bilesha Weeraratne

By Bilesha Weeraratne

Despite Sri Lanka’s 2018 Budget proposals presented on 9 November being built around blue-green colours, greenbacks (US dollars in a colour connotation) related to the country’s migrant workers toiling overseas received little or no attention.

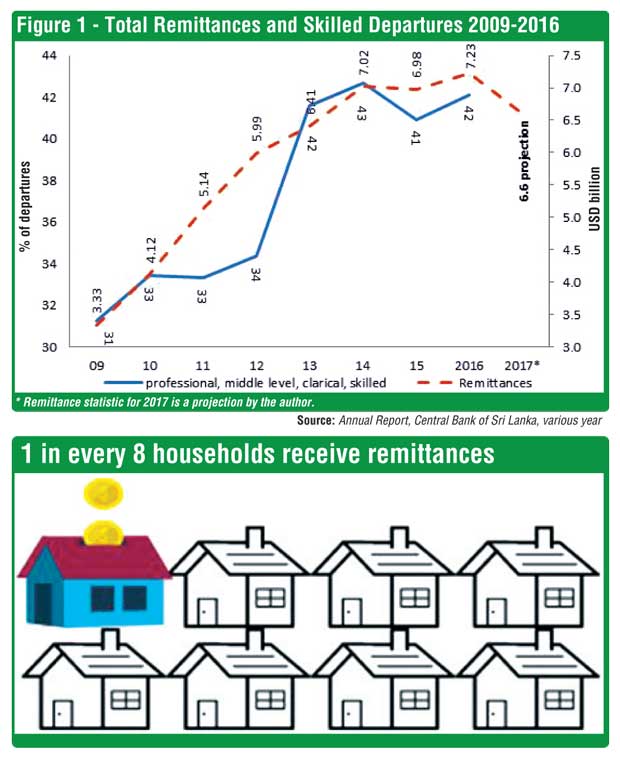

A good portion of Sri Lanka’s foreign exchange earnings are received as migrant remittances; in 2016, a total of 7.2 billion in greenbacks was remitted, which accounted for 8.9% of GDP, surpassing foreign exchange earned by apparel exports or tourism.

Remittances account for 80% of the trade balance, or 4.5 months’ worth of imports. Similarly, almost one in every eight households in Sri Lanka receives remittances, and annually, over 250,000 Sri Lankans leave for foreign employment. Yet, the proposed Blue-Green Budget had no reference to remittances, nor the migrant workers who send them home. Does this mean migration and remittances are not priorities of the Sri Lankan economy? One hopes not.

Previous proposals

Previous budget proposals have included a pension scheme for overseas employees (proposals for 2017), and dedicated immigration/emigration counters at the Bandaranaike International Airport for “Commercially Important Persons” heading to Middle Eastern countries (proposed for 2016), among others.

Indeed, the absence of any reference to migrants and remittances in the 2018 Budget appeared to generate speculation that a tax imposition was imminent on the remittances of migrant workers. The speculation was promptly addressed by the authorities to deny any intention to tax remittances (“No tax on remittances of migrant workers: Thalatha,” by Kalathma Jayawardhane, in Daily Mirror, Saturday 9 December, p. A4).

Vision 2025

To compensate for the absence of migration/remittance focus in the Budget proposals for 2018, Vision 2025 – the medium-term economic policy direction of the Government – notes that “the Government will only promote foreign migration in sectors without domestic labour shortages, and where there is potential for higher earnings and increased remittances”.

Migration and remittances in Sri Lanka today are at crossroads with fluctuations in remittances, and simultaneous changes in the composition of the skills mix of those departing. This signals a need for support and incentives to carve out a sustainable future trajectory for remittances.

Fluctuating remittances

Until 2014, remittances experienced a steady growth, with the five year annual average growth rate standing at 13.7%. This upward trend reversed in 2015, with a 0.5% decline to $ 6.98 billion. Coincidentally, in the same year, the share of skilled workers surpassed other skills groups. This change in momentum in remittance receipt was followed by a smaller than before growth of 3.5% in 2016 to reach $ 7.2 billion – just above the 2014 amount of $ 7.02 billion.

Against this backdrop, 2017 is also expected to record a decline in remittances and an increase in skilled migration. As a result, a decline in remittances to about $ 6.5-6.7 billion can be projected, based on available monthly remittance data. When such fluctuations occur to the amount of remittances received, while the share of skilled workers is rising, it is uncertain if the policy focus of attaining the twin objectives of higher earnings and increased remittances identified in Vision 2025 is achievable. Moreover, focusing only on the ‘promotion of foreign migration’ in sectors with potential for higher earnings and increased remittances appears to bank on the assumption that those with potential for higher earning and remittances will in fact remit to Sri Lanka.

Earnings vs. remittances

The occupational categories and associated benefits of better skilled workers from Sri Lanka indicate that they would earn higher salaries than lower skilled workers or housemaids. But compared to lower skilled migrants, skilled workers are more likely to migrate as families, leaving fewer ties in the home country. This may causes Sri Lanka’s receipt of remittances to decline in the face of growing skilled and professional migration. In the absence of a clear understanding of the dynamics between remittances and changes in skills composition of departures, incentive schemes to boost growth in remittances would be beneficial. Hence, the 2018 Budget would have been the ideal platform to pave the way towards the remittances vision identified in Vision 2025.

Value and frequency of remittances

Value and frequency of remittances

One of the compelling issues in migration and remittances that could have been addressed via the Blue-Green Budget is the promotion of remittances by better skilled migrants. Two critical areas to target in terms of remittances by skilled migrants are the value of each remittance transaction and the regularity/frequency of remittances.

Possible proposals to enhance the value of remittances include payment of bonus interest for accounts that receive monthly remittances in excess of a specified amount, and payment of bonus interest for accounts that receive an annual total remittance in excess of a specified amount. Viable incentives to promote regular remittances include special higher interest rates for savings/foreign currency accounts that receive regular remittances, and special lower interest rates on loans (housing/student/etc.) for households receiving regular remittances.

Informal remittances

Apart from the documented remittances, a significant portion of remittances to Sri Lanka are believed to be channelled via informal channels. The Foundation for Development Cooperation (2007) estimates that informal remittances account for about 50% of all remittances to Sri Lanka, while a Gallop Study (2013) found that about 84% of their sample of migrants originating from Sri Lanka have used informal channels of remitting.

Often these informal channels operate via networks in sending and receiving countries, where a broker in Sri Lanka delivers money from his cash reserve or account at the request of his counterpart at the destination country. The speed, coverage, and flexibility of these transactions contribute to the popularity of informal remittances. However, from an economic point of view, one downside of informal remittances is that the relevant amounts of greenbacks never reach Sri Lanka. Hence, the diversion of informal remittances to the formal channel would increase the flow of greenbacks to Sri Lanka.

Some efforts the Budget proposals could have aimed at are channelling greater investment into remittance technology, minimising restrictions on foreign currency accounts (subject to changes introduced in the new Foreign Exchange Act of 2017), providing incentives to the banking sector to expand geographic coverage, promoting flexibility of remittance products, incentives to micro-finance institutions to engage in the remittance transfer process, and incentives to minimise cost of remittances via formal channels.

Finally, having not made it to the Blue-Green Budget, perhaps the above proposals to increase greenbacks could at least find their way into the near term economic policy direction of the Government, identified as Vision 2020, through the interim budgets that will follow.

[Bilesha Weeraratne is a Research Fellow at the Institute of Policy Studies of Sri Lanka (IPS). To share your comments with the author, please write to [email protected]. For more articles, visit our blog http://www.ips.lk/talkingeconomics/.]