Friday Feb 20, 2026

Friday Feb 20, 2026

Tuesday, 10 September 2024 00:21 - - {{hitsCtrl.values.hits}}

By Pathfinder Foundation

Introduction

This policy brief is aimed at outlining key areas of reforms for a new Government. Whatever the emerging political aspirations of the crisis-battered Sri Lankan society, the new Government that will be elected at the forthcoming presidential and parliamentary elections is bound to face a series of policy challenges. The continuity of economic recovery from the crisis should be ensured, and the possibility of another crisis should be avoided. A clear vision to set the economy on a sustainable growth path is required.

The policy options of old-fashioned tax cuts, politically motivated Government jobs, salary hikes, and free hand-out deliveries have now ended because the Government’s fiscal discipline is a priority. Only higher economic advancement based on production and productivity growth would pave the way for the people of Sri Lanka to acquire high living standards and realise their future aspirations of living in a developed country.

The policy challenges of a new Government are not about an ideological debate and discussion. Instead, they are about a pragmatic and robust reform agenda to build an enabling environment for economic recovery and sustained economic growth.

Economic crisis: Genesis

People’s ‘two-fold’ distress

Sri Lankans are now aware of the harsh reality of an economic crisis they had never experienced during the past 75 years. People suffer from the crisis in two ways: (a) they have faced the adverse effects of sudden economic collapse, such as domestic supply shortages, inflationary consequences, economic contraction, and income and job losses, and (b) they must bear the enduring burden of immediate policy responses to the crisis, such as direct and indirect tax increases, fuel and electricity price hikes, freezing nominal wages, and Government expenditure cuts. The cumulative effect of all these is that people’s living standards have deteriorated sharply while their poverty and vulnerability levels increased rapidly.

It’s a ‘man-made’ crisis

The crisis built up slowly over time, but the resultant collapse was sudden. It is a big question why a country, which had admirable economic and welfare standards throughout its post-independent history, has now fallen into an economic crisis of proportions and has been reduced to a ‘hand-to-mouth’ status of existence. It is argued that policy blunders by Sri Lankan policymakers over a long period created a fertile ground for its economy to be vulnerable to external shocks. “COVID-19 (external shock) was just the trigger, not the cause, of the crisis”. The policy reform process of the country, which evolved through 1977 and 1989, did not move forward after the late 1990s. Instead, the policy environment that emerged since the turn of the century was characterised by production with non-tradable and anti-export biases. The policy reform program that was previously implemented was reversed in the early 2000s.

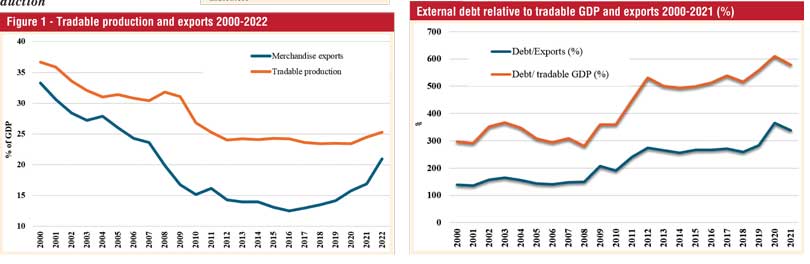

The non-tradable bias of production

Part of the production activities are categorised as ‘non-tradable’, i.e., those that can be only bought and consumed where they are produced; hence, they are primarily directed towards catering to the local market. Since the early 2000s, the contribution of tradable production to GDP growth has been declining (Figure 1). Sri Lanka’s GDP growth was increasingly dependent on non-tradable production sectors such as construction, infrastructure projects, power and energy, utilities, transport, telecommunication, finance, public administration, defence, education, and health. Compared with these non-tradable sectors, the growth of ‘tradable sectors’ such as agriculture and manufacturing has been limited.

A closer examination of public investment reveals that the Government has played a major role in the expansion of the non-tradable sector. This policy of public investment to promote and expand the non-tradable sector, largely borrowing from external sources, has increased the budget deficit, external deficit and overall public debt. Furthermore, a study by the World Bank points to the fact that growth performance during the post-war period (2009-2014) has been mainly led by the non-tradable sectors within which construction, transport, domestic trade, banking, and insurance and real estate contributed to 50% of the total growth.

The other side: anti-export bias

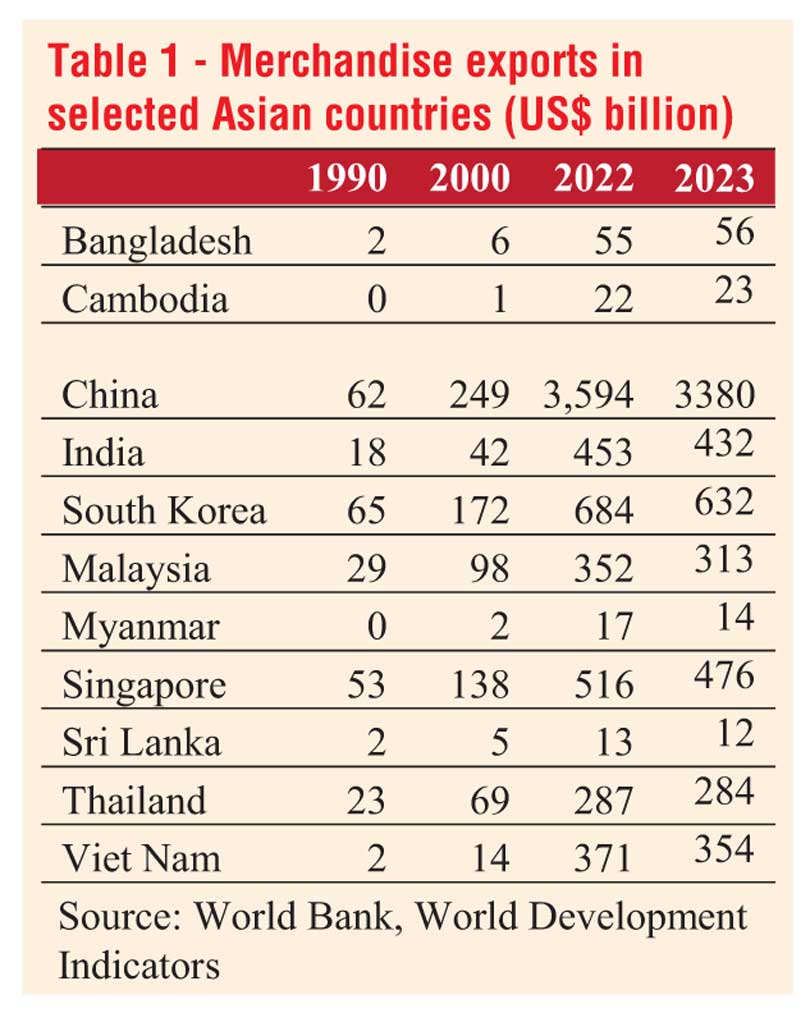

It is amazing to see that, despite being a ‘liberalised’ economy for over 45 years, Sri Lanka has been able to generate only $ 12 billion worth of merchandise exports as of 2023. Sri Lanka experienced a rapid expansion in manufactured exports and a change in its export mix during the initial period of trade liberalisation. However, the country failed to maintain that export growth momentum during the latter period of trade liberalisation after the 1990s. From a comparative perspective, it is indisputable that Sri Lanka’s export growth has lagged behind many of its peer countries in the region, including those neighbouring countries that initiated trade liberalisation much later than Sri Lanka (Table 1). The slowdown in export growth momentum in Sri Lanka beginning in the early 2000s can be attributed mainly to the policy bias against exports – an inevitable outcome of increased protectionism and non-tradable bias in production.

Two episodes of performance

The growth performance of Asian countries is depicted in two episodes, one based on ‘trade expansion’ and the other on ‘fiscal expansion’. In some countries, increased exports have become the main growth driver. Adopting such policies has enabled them to achieve enhanced trade performance and sound management of the government budget. This has been the story of successful export-oriented economies in East and Southeast Asian countries. In contrast, increased government spending has become the growth driver in some other countries, making their growth dependent more on fiscal expansion than trade expansion. Growth has become unsustainable, on the one hand, because it requires repeated increases in Government spending, largely through credit financing. On the other hand, growth became increasingly biased towards ‘non-tradable’ sector expansion, but not emanating from export growth. The need for continuous increases in government spending caused a widening budget deficit and growing public debt. The increased bias towards the non-tradable sector and anti-export bias policies led to a widening trade deficit.

Sri Lanka’s external debt conundrum: earning rupees and paying dollars

Sri Lanka is a classic example of a Government’s attempt to sustain growth in non-tradable sectors with forgone policy reforms towards export promotion. Since 2000, successive governments have placed increased reliance on non-tradable sectors as the major source of economic growth, which has become a key feature of the Sri Lankan economy.

As anticipated, such policies have led to a widening of both the budget deficits and trade deficits. Sri Lanka has persistently faced this ever-growing twin deficit during the last two decades. As foreign borrowings on concessionary terms depleted, Sri Lanka turned to foreign commercial borrowings in 2007 by issuing International Sovereign Bonds (ISBs). From 2007-2019, Sri Lanka borrowed $ 17.6 billion from ISBs. Compared with that, the country attracted only $ 11.3 billion in foreign direct investments (FDIs), which also flowed primarily into the non-tradable sector. Sri Lanka had already reached a point where debt payment obligations were met with further borrowings from domestic and foreign sources.

The issue of foreign debt payments became persistently more critical because rupee incomes generated from investments in the non-tradable sector did not help service the foreign debt obligations in foreign currency. Consequently, successive Governments have been compelled to borrow more to service maturing external debts in addition to recurrent fiscal deficits yearly over a considerable period of time. This untenable situation plunged the country into a vicious circle of large fiscal deficits and unfavourable debt dynamics.

Although the country narrowly escaped possible collapse several times previously, the COVID-19 pandemic and a series of internal policy errors triggered the current economic crisis. Sri Lanka suspended the payment of bilateral and private foreign debt on 12 April 2022, anticipating a debt-restructuring plan and a recovery program through the IMF.

Recovery from crisis

Given the unprecedented economic crisis that Sri Lanka currently faces, the country needs two-tier policy reforms. The first is implementing an immediate set of policy reforms aimed at economic stabilisation, including debt sustainability. These policy reforms are intended to ensure ‘recovery from the crisis’ as per the Extended Fund Facility (EFF) agreement that the Sri Lankan government has entered with the IMF and approved on 20 March 2023. The second set of long-term reforms is required to ensure ‘economic progress beyond recovery’ by pursuing concrete policies addressing “non-tradable sector bias of production” and “anti-export bias” in the economy. However, there are many interrelationships between the two-tier reforms as they could overlap and reinforce each other. Economic stabilisation cannot be sustained without unlocking the country’s growth potential, which should be realised by eliminating the obstacles to export growth and creating a conducive environment for private investment.

Five key pillars of the IMF arrangement

The stated objective of the EFF arrangement with the IMF is to “restore Sri Lanka’s macroeconomic stability and debt sustainability, mitigate the economic impact on the poor and vulnerable, safeguard financial sector stability, and strengthen governance and growth potential”. It is based on five key pillars: (i) revenue-based fiscal consolidation, (ii) restoration of debt sustainability, (iii) price stability and rebuild foreign reserves, (iv) financial sector stability, and (v) structural reforms:

Revenue-based fiscal consolidation with efficient tax administration is required to reduce the budget deficit to manageable levels and to minimise borrowing needs. The government does not have an efficient tax collection system for direct taxes. Consequently, tax revenue has been disproportionately based on indirect taxes. Fiscal consolidation could be supported further by adopting cost-recovery of fuel and electricity prices by ending the country’s energy price subsidies. However, given the crisis’s severe impact on increased poverty and vulnerability, Sri Lanka needs a targeted, time-bound social safety net scheme.

Sri Lanka’s public debt had increased to 128% of GDP by the end of 2022. It is unsustainable because the government cannot meet debt repayment obligations with its current level of tax revenue. As per estimates, public debt must be reduced to 95% of GDP by 2032 to make it sustainable. This target could be achieved through debt restructuring on the one hand and improving the capacity to meet future debt obligations with fiscal consolidation on the other. Additionally, external debt sustainability requires reducing the current debt servicing of 9.4% of GDP in 2022 to an annual ceiling of 4.5% of GDP by improving the foreign exchange earning capacity through export promotion.

Sri Lanka needs a “multi-pronged strategy” to restore price stability, as average inflation was 46.6% in 2022. Hyperinflation has wiped out the people’s real income, causing a sharp increase in poverty and vulnerability. It is also necessary to build up foreign reserves, which had dropped below $ 2 billion by the end of 2022, equivalent to just one month’s imports. The usable forex reserve by the middle of April 2022 was negligible. While maintaining a flexible exchange rate, Sri Lanka should improve its ability to purchase essential goods abroad.

The financial sector’s stability must be strengthened to eliminate the stress on the banking sector and maintain a healthy monetary policy discipline. The economic crisis has adversely affected the financial sector’s stability. The Central Bank must do away with its “bad habit” of printing money to meet the expenditure needs of the government as well while ensuring its independence. This policy has already been adopted, but the country must continue to adhere to it.

Finally, the country needs to undertake structural reforms to unlock its growth potential and to address corruption vulnerabilities. As a medium-term program, growth is essential to enhance income generation and job creation, address the crisis’s impact on the nation, and support fiscal consolidation with enhanced tax revenue for the Government. At the same time, Sri Lanka’s growth potential has been blocked by its corruption vulnerability, which has been growing but ignored for a long time.

Economic turnaround

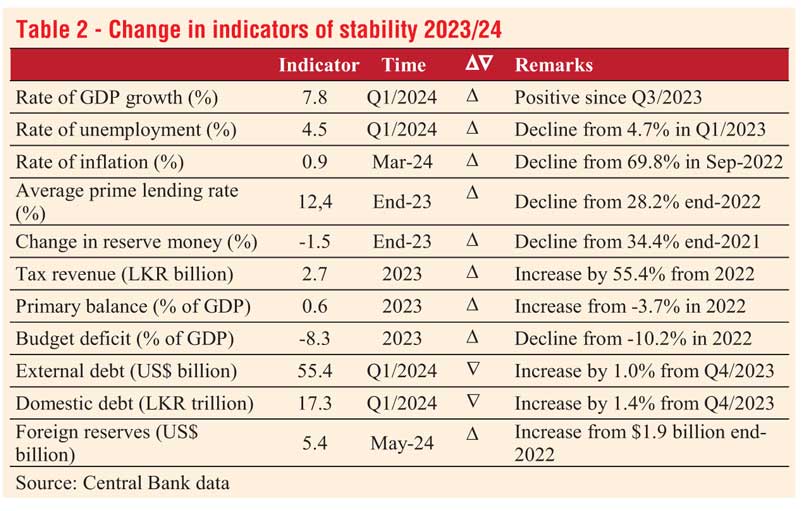

During the past two years (2022-2023), with IMF assistance, the Government has adopted reforms and implemented a series of new policy measures aimed mainly at restoring macroeconomic stability. Although there have been implementation weaknesses and structural rigidities, Sri Lanka has made remarkable improvements, as acknowledged by the IMF, which continues to recognise this in its biannual assessments. Sri Lanka has been able to turn around its crisis-ridden economy within a relatively short period – as short as two years, and to stop potential deterioration from falling into a much deeper crisis (Table 2).

Improvement in stability, remarkable

Economic contraction during five consecutive quarters ended in the third quarter of 2023 when the real GDP growth rate turned negative to positive. The rate of inflation started to fall after its highest rate of 68.9%, reported in September 2022, reaching a single-digit level in mid-2023. Accordingly, the interest rates that rose steeply to around 30% in 2022 have also come down to around 8.25- 9.25% in the second half of 2024. This is based on the Standing Deposit Facility Rate (SDFR) and the Standing Lending Facility Rate (SLFR) announced by the Central Bank of Sri Lanka. Fiscal consolidation improved with increased tax revenue by more than 55% in 2023. The Government budget reported a positive primary balance of 0.6% of GDP and a reduction in the fiscal deficit. At the same time, the Central Bank has continued building up its official foreign reserves, which increased to over $ 5 billion by May 2024. Although external and domestic debt has increased moderately by around 1% during the first quarter of 2024, there has been a remarkable slowdown in public debt accumulation.

To be contd.