Saturday Feb 21, 2026

Saturday Feb 21, 2026

Tuesday, 21 November 2017 00:00 - - {{hitsCtrl.values.hits}}

By Dr. P. Nandalal Weerasinghe, Senior Deputy Governor, Central Bank of Sri Lanka

While monetary aggregate targeting remained the framework for the conduct of monetary policy in Sri Lanka, the exchange rate regime also underwent a gradual evolution. The managed floating exchange rate system broadly remained a crawling band arrangement as the margin associated with the foreign exchange transactions was increased from time to time.

The degree of Central Bank intervention in the foreign exchange market varied over time with balance of payments developments and the view of the Central Bank on the direction of the exchange rate.

Under this monetary targeting framework with a crawling exchange rate, achieving price stability proved challenging, as successive governments continued to run high fiscal deficits even after the completion of the accelerated Mahaweli scheme to finance large scale housing and road development programmes. In addition, the three decades of ethnic conflict required successive governments to spend more money on defense expenditure. In order to maintain competitiveness of the rupee, the Central Bank had to let the currency depreciate to, at least partly, compensate for the inflation differential between Sri Lanka and its trading partners under the crawling peg system. Even though this arrangement helped to alleviate the adverse impact on exports to some extent, higher domestic demand created through excessive fiscal deficits led to large current account deficits in the balance of payments, making it difficult to maintain the crawling peg without a sharp depreciation.

By the year 2000, Sri Lanka experienced a significant decline in its official international reserves, as a result of the considerable increase in expenditure on imports. The increased demand for foreign exchange placed tremendous pressure on the exchange rate. Within the managed floating exchange rate regime, this naturally resulted in increased pressure on international reserves. In order to defend the managed float, the Central Bank raised its policy interest rates to unprecedented levels, which later proved not only to be an unsuccessful exercise but also a costly experiment, which largely contributed to the only negative annual real GDP growth rate of the country’s history of -1.5 per cent in 2001.

This prompted the Central Bank to revisit its exchange rate policy. On 23rd of January 2001, the Central Bank took the major step of allowing the commercial banks to determine the exchange rate depending on the supply and demand of foreign exchange in the domestic foreign exchange market. With this move, the Central Bank refrained from announcing daily buying and selling rates of foreign exchange, thus allowing freer foreign exchange transactions. The change in the exchange rate regime resulted in an overshooting effect with the rupee depreciating by Rs. 13 from Rs. 98 per US dollar within the first three days, but a relatively quick stabilisation of the exchange rate followed.

As the use of monetary policy to defend the foreign exchange rate was no longer necessary under the floating exchange rate regime, the Central Bank of Sri Lanka was able to conduct monetary policy with an increased focus on achieving the bank’s objective of price stability. However, maintenance of price stability came under heavy pressure under this regime whenever aggregate demand was excessive as a result of expansionary fiscal policies.

Therefore, at times of such excessive domestic demand through fiscal dominance, the Central Bank of Sri Lanka intervened in the foreign exchange market to defend the exchange rate from depreciation.

Although this was done with the good intention of maintaining macroeconomic stability in difficult times, experience repeatedly showed that managing the exchange rate extensively was always associated with a substantial loss of limited international reserves followed by a large depreciation. The most recent of such events were in 2011/2012 and 2015. During the 2011/2012 episode, the Central Bank supplied $ 4.2 billion to the market on a net basis, while the Central Bank supplied $ 3.2 billion to the market on a net basis during the year 2015. In spite of these considerable losses of reserves, the rupee depreciated against the US dollar by 13.5% by the end of the 2011/2012 episode and by 9.0% during 2015.

Since then, the Central Bank has explicitly announced that international reserves will not be used to defend an overvalued exchange rate. Instead, the Central Bank intervention in the foreign exchange market will aim to buildup international reserves. So far during 2017, the Central Bank has been able to purchase over $ 1.3 billion from the market on a net basis for this purpose, and improved market confidence is shown by the limited depreciation of the currency this year.

Returning to the previous discussion, it was clear by late 1990s and early 2000s that a serious rethink of central banking in Sri Lanka was necessary. In addition to the increasingly popular view within international central banking and academic circles that price stability must be the overriding objective of a central bank, financial innovations, including the development of electronic payments and fund transfer systems, also prompted the Central Bank to upgrade its view on financial system stability.

These factors, as well as many others which are beyond the purview of this speech, prompted the Central Bank of Sri Lanka Modernisation Project, resulting in legislative, procedural and operational changes in relation to central banking in Sri Lanka.

With regard to legislative changes, the amendments to the Monetary Law Act (MLA) in 2002 were the most important. Accordingly, the multiple objectives of the original MLA, which included stabilisation and development objectives as well as maintaining domestic and external value of the rupee, were streamlined to define the core objectives of the Central Bank as maintaining economic and price stability and financial system stability.

By this time, the Central Bank had gradually moved away from direct controls to market based tools of monetary policy, a process which started with the adoption of open economy policies since 1977. The significant advancement in monetary policy operations during this period was the introduction of the Repurchase rate and the Reverse Repurchase rate of the Central Bank.

The Central Bank introduced its repurchase facility in 1993 to mop up overnight excess liquidity from the market, while introducing the reverse repurchase facility in 1995 to inject overnight liquidity to the market. These two rates served as the floor and the ceiling for movements of the interbank call money market rate.

This policy interest rate corridor was used from early 2000s to signal changes in the monetary policy stance of the Central Bank. Today this policy corridor is called the Standing Rate Corridor with the floor and the ceiling rates being known, respectively, as the Standing Deposit Facility Rate (SDFR) and the Standing Lending Facility Rate (SLFR) of the Central Bank of Sri Lanka. Open market operations are conducted in a more active auction based framework with overnight, short-term and long-term operations to maintain market liquidity and thereby market interest rates in line with the announced monetary policy stance of the Central Bank.

The key operational changes to the conduct of monetary policy included the establishment of the Monetary Policy Committee (MPC) of the Central Bank in 2001 to strengthen monetary policy analysis and to improve the transparency of the decision making process. The Central Bank also began issuing regular press releases on monetary policy decisions to the public, based on an advance release calendar.

This press release was often followed by a press conference chaired by the Governor and accompanied by the senior officials of the Central Bank. The Central Bank also introduced a Monetary Policy Consultative Committee (MPCC) comprising academics, professionals and private sector representatives, enabling the Central Bank to obtain views of the private sector to be used in the monetary policy formulation process. In addition, the Central Bank started to enunciate its monetary and financial policies for a medium-term horizon though a Road Map, which was unveiled at the beginning of each year.

In spite of these modifications to the framework of conducting monetary policy over time, Sri Lanka continued to suffer from double digit inflation until 2009 as a combined outcome of high Budget deficits and loose fiscal policy, reactive rather than proactive monetary policy, frequent domestic supply disruptions and international commodity price shocks.

In June 2008, inflation increased to 28.2%, the highest level of inflation since 1980s. In order to manage this situation within the monetary targeting framework, the Central Bank used strict quantitative monetary targets with increased policy interest rates while also imposing restrictions on access to the Central Bank reverse repurchase facility. In a display of validity of monetary targeting, the Central Bank was able to bring down inflation from the peak to near zero levels within a 12-month period. It was the sharpest disinflation the country has experienced in the history of Sri Lanka, but it must also be noted that the weak global commodity prices also contributed to this decline to some extent.

Nevertheless, the intent of the Central Bank to maintain inflation at mid-single digit levels, which was made clear through action as well as through communication, enabled the Central Bank to change the mindset of the people that Sri Lanka is typically an economy with double digit inflation. The change in the mindset was visible in improving inflation expectations.

Since February 2009, inflation has remained in single digits, and 105 consecutive months of single digit inflation is considered an achievement in the recent history of Central Banking in Sri Lanka.

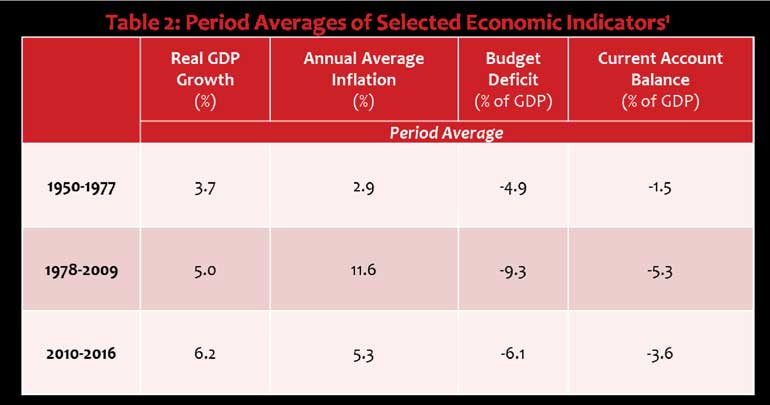

However, Sri Lanka’s achievement of single digit inflation for 105 consecutive months had little to do with monetary aggregate targeting. From July 2009 to September 2017, the year-on-year broad money growth was, on average, 17.1%. Year-on-year inflation during the same period averaged 5.2%.

Based on the earlier discussed Fisher’s Quantity Theory of Money, the gap between these two figures, that is 11.9%, must reflect average real economic growth during this period. However, real economic growth averaged only 6.0% during this period. If the argument is reversed, there is a gap of 11.1% between broad money growth and real economic growth.

According to the Quantity Theory, this should reflect average inflation during the period, which was not the case. Even if some allowance is made for changes in velocity of money or money demand due to possible behavioral changes and financial sector development, the growth of money vs. the real growth of the economy and inflation cannot be explained for this period.

This was sufficient evidence that the strong and reliable relationship between the goal of price stability and the nominal anchor of money growth, which was essential for the success of the monetary aggregate targeting framework, has significantly weakened over time.

This phenomenon was not limited to Sri Lanka, but was observed over time in many other economies as well. With the ending of monetary aggregate targeting in Canada in as early as 1982, Gerald Bouey, Bank of Canada Governor at the time famously stated “we did not abandon monetary aggregates. Monetary aggregates abandoned us.” Even the recent experience with quantitative easing in many advanced economies yet again proved that the tremendous expansion of central bank balance sheets that these countries undertook was insufficient to raise either growth or inflation.

Earlier it was argued that Sri Lanka’s achievement of single-digitinflation for 105 consecutive months had little to do with monetary aggregate targeting. Instead, it was a result of the Central Bank’s ability to anchor inflation expectations, by repeatedly emphasising its utmost desire to maintain inflation at mid-single digit levels. The behaviour of the Central Bank during the 2008-2009 episode of disinflation would have raised credibility of monetary policy.

Improved communication also would have played a key role in this achievement. It must be noted that the neighbouring economies struggled with double digit inflation during some parts of the same period. For example, India was unable to tame inflation until 2014. One might argue that international commodity prices were in our favour. However, this was not always true, as global crude oil prices remained, on average, above $ 100 per barrel during the period from February 2011 to September 2014.

Therefore, without a formal announcement, the Central Bank of Sri Lanka, similar to many other central banks in the world, has moved to a monetary policy framework governed by expectations and credibility, rather than by monetary aggregates or exchange rates.

In the global economy, such a monetary policy framework that emphasised the role of expectations and credibility existed, and it was known as “inflation targeting” that I briefly referred to at the beginning.

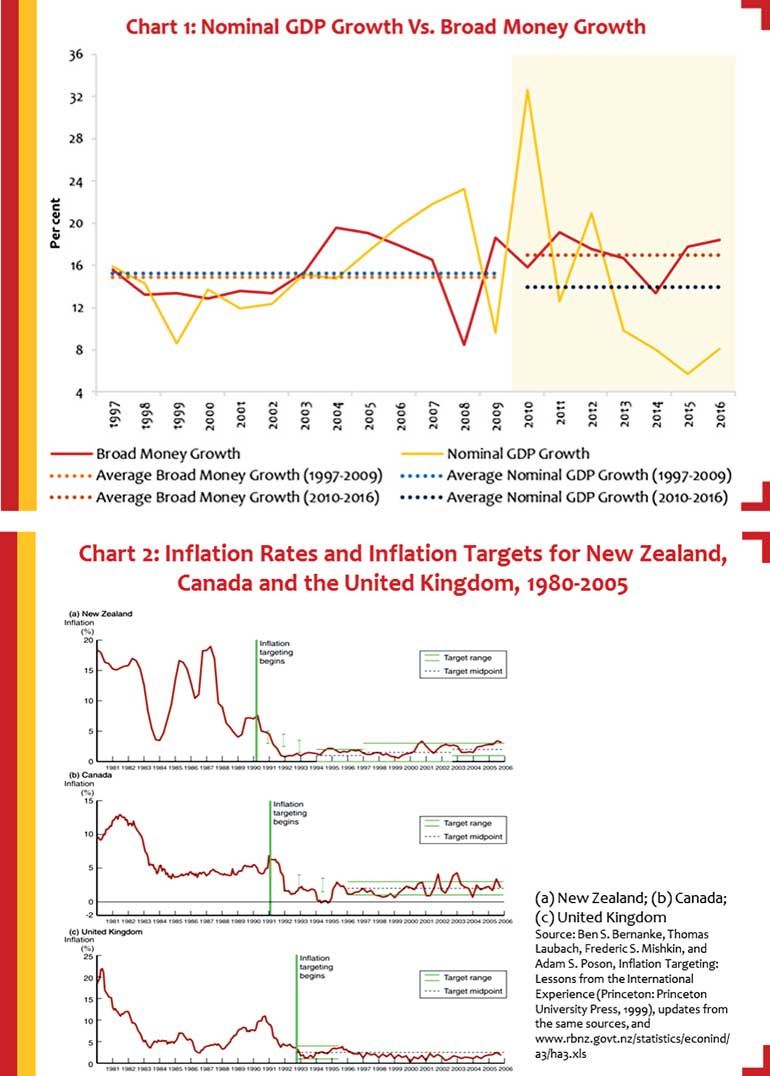

First adopted by New Zealand in 1990, inflation targeting was chosen as the monetary policy framework in Canada, the United Kingdom, Australia, and Sweden in quick succession. Encouraged by the success of inflation targeting, a number of other advanced economies as well as emerging market economies adopted this framework thereafter. These countries used inflation targeting either to bring down inflation from stubbornly high levels or to maintain inflation at low and stable levels on a sustained basis.

Inflation targeting is generally characterised by an announced inflation target; an inflation forecast, which facilitates forward looking monetary policy decision making; and a high degree of transparency and accountability. According to Lars Svensson, the Swedish economist who later served as Deputy Governor of the Riksbank, this policy framework encompasses a trinity of a mandate for price stability, independence, and accountability for the central bank, which enables anchoring of inflation expectations effectively.

In practice, inflation targeting is flexible rather than strict. According to Svensson, flexible inflation targeting means that monetary policy aims at stabilising both inflation around the inflation target and the real economy, whereas strict inflation targeting aims at stabilising inflation only, with little regard to the stability of the real economy.

A strict inflation targeter would be who Mervyn King, the former Governor of Bank of England, called an “inflation nutter”. Most of the central banks do not only aim at stabilising inflation around an inflation target, but also put an effort into stabilising real economic variables. This effort is described by the time horizon in achieving the inflation target, which dampens the adverse impact of policies on the real economy. Therefore, an important feature of flexible inflation targeting is that the inflation rate will be on average at target, but perhaps not every month.

A key advantage of inflation targeting is that it is easier for the general public to relate to. Since inflation is well understood by the public, the inflation forecast will serve as an ideal anchor and, with improved communication, will help bridge the information gap between the central bank and the public. Reference to such a straightforward target, rather than to an elusive monetary target, will ensure increased transparency and accountability while enabling the public to understand policy shortcomings.

Global experience has also shown that in adopting inflation targeting, a country needs to fulfill several prerequisites, particularly in terms of the legal and institutional framework. These include central bank independence and strong mandate for price stability, strong fiscal position with freedom from fiscal dominance, a flexible exchange rate regime, a well-developed financial system, a sound technical infrastructure for inflation forecasting, and transparent policies to build accountability and credibility of the central bank.

In particular, with regard to fiscal dominance, other countries had developed mechanisms to stop monetary financing of fiscal deficits, particularly through subscribing to government securities auctions and the provision of interest free funds to the government through an advance account as observed in Sri Lanka. Instead, other central banks would purchase government securities from the secondary market to influence monetary conditions as and when necessary.

(To be continued tomorrow)

[Footnote: I would like to note that the views expressed in this oration are my own as an economist and do not necessarily reflect the views of the Central Bank of Sri Lanka. I also would like to acknowledge the technical support received in preparing the oration from Dr. Chandranath Amarasekara and his team at the Economic Research Department of the Central Bank of Sri Lanka.]

Click here to read Part I

Click here to read Part III