Monday Feb 23, 2026

Monday Feb 23, 2026

Monday, 8 November 2021 00:00 - - {{hitsCtrl.values.hits}}

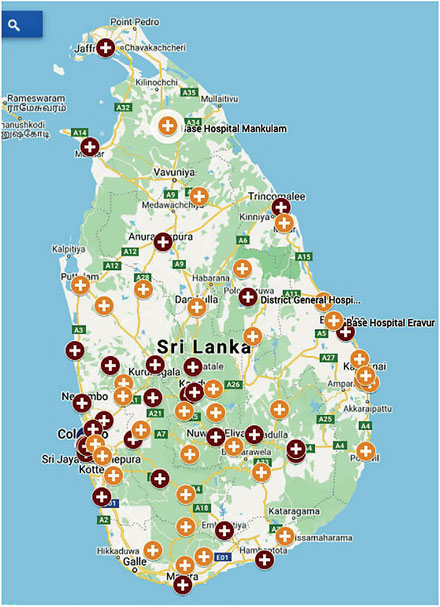

Geographical coverage of Group 1

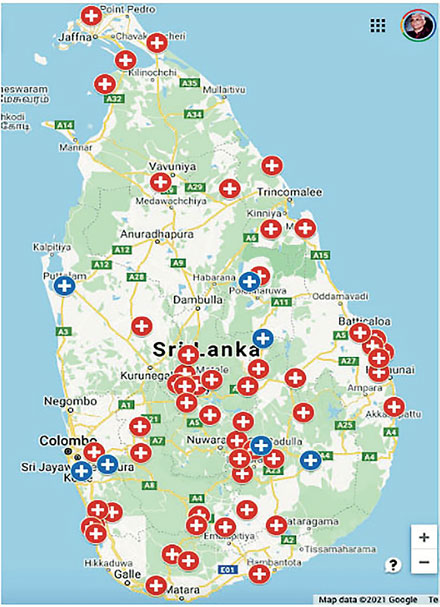

Geographical coverage of Group 2

|

| Segregation bins for waste |

|

| Waste clearing

|

A recent photograph showing used cotton swabs strewn all over the grounds of a COVID-19 vaccination centre in Colombo was shared widely on social media. This is just an example of the lack of awareness and total disregard for health and hygiene even despite the dire warnings of a global infectious pandemic. If this is the scene at a vaccination centre, imagine the situation in a healthcare facility where syringes and other harmful contaminants are being improperly disposed of?

Hospitals, in general, have poor records when it come to the proper disposal of healthcare waste. Over the years, there have been alleged accusations of these wastes being dumped in open landfills, or polluting environs while the COVID-19 pandemic has added to the burden of most hospitals and healthcare facilities Hospitals are overcrowded, understaffed and completely outdone by the highly contagious pandemic, leaving little respite for adjustment and preparation especially in the disposal of infectious medical waste and its adverse risk of contamination associated with waste management to waste cleaners, health workers, patients and the community in general.

COVID-19 generates a different type of healthcare waste, including biohazard waste materials, and its mismanagement could cause serious “knock-on” effects on human health and surrounding environs. Therefore, the safe handling and final disposal of such waste is a fundamental step in the fight against the pandemic and the entire sustainability cycle.

The effective management of biomedical and healthcare waste requires appropriate identification, separation, collection, storage, transportation, treatment and disposal as well as a sound data management system and comprehensive training of health personnel. Although this medical waste generation and its consequences are important for planning and policy development, there is a lack and limitation of the national data availability and its accuracy in Sri Lanka.

Rapid assessment

With this in mind, a rapid assessment of the prevailing healthcare waste management systems in Sri Lanka was conducted to evaluate the type and amount of healthcare waste generated in the country, the current management practices, gaps from an environmental and social safeguard point of view, and recommendations to improve healthcare waste management in Sri Lanka.

The rapid assessment from October 2020 to March 2021, undertaken by United Nations Development Programme (UNDP) in Sri Lanka on behalf of the Ministry of Health, was conducted at 40 healthcare facilities across the country with the view to make sound conclusions and recommendations for a practical way forward.

Healthcare facilities were divided into three groups; Group 1 included State sector large scale hospitals above base hospitals, Group 2 comprised State sector small scale hospitals below divisional hospitals, and in Group 3 were private healthcare facilities. Meanwhile, taking into consideration the current situation where in-person data collection was not possible, online data collection methods were used for this purpose.

According to the data collected, the estimated total infectious and sharp wastes (a form of biomedical waste that could puncture skin) generated from Group 1 and 2 is 25.38 tons per day, out of which about 94% is generated in healthcare facilities in Group 1. These include 31% of radioactive waste, and 91% of laboratory chemical waste. Group 2 reported only 24% of these wastes. Both groups reported 80.3% and 65.7% respectively for pharmaceutical waste.

An area of priority for waste management is segregation of components into reusable and non-usable, and hazardous and non-hazardous materials. The waste categories used in segregation show that, in general, infectious wastes and sharps have higher emphasis in segregation at healthcare facilities in both Group 1 and Group 2, along with plastic, glass and general waste types. Meanwhile, biodegradable waste has received relatively lower attention in segregation programmes. A few facilities in both categories have indicated the absence of segregation, which needs to be attended to urgently due to potential health and environmental hazards.

Incineration issues

Incineration is used to destroy most hazardous healthcare wastes and is still widely used. However, the findings revealed the lack of proper maintenance and operation of incinerators, especially the emission levels released from the stack. Whilst many of these incinerators are serviced by staff with a lack of knowledge on these processes at the said healthcare facility, lack of funds and spare parts adds to the poor management of incinerators.

With regard to hazardous waste treatment, it is evident that Group 1 performs better than Group 2 with only seven of the 73 healthcare facilities found to burn their clinical wastes in open pits. According to the responses, the amount of clinical wastes disposed through open burning is about 106 tons per year. Another 1,274 tons of clinical wastes is annually treated using Metamizers, a hybrid autoclave system that is a clean, efficient and environmentally friendly alternative to common medical waste disposal methods like incineration. If autoclaved waste in Metamizers is properly disposed of in sanitary landfilling, it should result in minimum impact to the environment. However, it was evident during the observation visits that some of the healthcare facilities do not have access to proper facilities for the disposal of residue wastes from Metamizers.

The findings also reveals that approximately 3,015 tons of waste is sent to a third-party private company for incineration annually by Group 1.

This emphasises the importance of having good, centralised incinerators that receive waste from several healthcare facilities so that they can be operated continuously. If all the waste is incinerated in such facilities, the total release of dioxin/furans drops to 1.300 g TEQ. Out of the total waste generated from Group 2, approximately 55% is openly burnt, and another 16% is incinerated. A total of 13.36 g of TEQ Dioxin and Furan is estimated to emit from Group 2 annually. Even though Group 2 generates about 6% of clinical waste from Government healthcare facilities, the improper disposal of these waste results in approximately 40% of the total emission of dioxins and furans, a toxic chemical found in very small amounts in the environment, from government healthcare facilities. This is indicative of the importance of proper disposal of clinical waste from small healthcare facilities.

Managing mercury

Meanwhile, the Ministry of Health has taken steps to phase out mercury-containing measuring devices. The findings revealed a total of 179 kg of mercury is released to the air annually during the burning and incineration of clinical wastes from Group 1. The estimated mercury emission from Group 2 is 10 kg/y.

According to US-EPA, the index for reporting air quality, the maximum permissible daily intake is 0.1 -g/kg of body weight. Therefore, the permissible maximum yearly intake of mercury for an average person weighing 70 kg is 2.3g. Considering the persistent nature of mercury, though as not severe as dioxin and furan emission, the health and environmental impact of mercury emission from healthcare waste management is considerable.

Additionally, the health and safety aspects including the occupational health and safety of staff of the healthcare facilities should be considered and it is important to develop and implement a mitigation strategy for the safety of the staff as well as other stakeholders including the general public. This should be followed by comprehensive educational and staff-training initiatives with mandatory certified orientation programmes in the areas of health and safety and its implications on Government and private sector healthcare facilities.

While there is a direct financial cost, the mismanagement of healthcare waste has an even bigger economic cost arising from negative environmental and social impacts.

Recommendations

After considering the assessment conducted within the healthcare sector, several recommendations were made based on the outcomes. Firstly, a well-coordinated and collaborative effort needs to be implemented at all levels of the governance system (Central Government, Provincial Councils and Local authorities) including the Ministries in charge of health and environment, along with environmental regulatory bodies such as central and provincial environmental authorities, facilitating bodies such as Western Province Waste Management Authority, National Solid Waste Management Centre and the Urban Development Authority. These Government agencies must engage a high-powered national level multi-stakeholder steering committee for healthcare waste management.

The strict standardisation of waste collection in colour-coded polythene bags by material and size, types of waste collection bins supplemented with easy-to-understand visuals or instructions, and a collapsible form of waste transport trolleys are a few suggestions from the report. Other recommendations include providing easy-to-use weighing facilities for recording and documenting of waste generated, segregated and treated, standardising proper isolation units for infectious waste, introducing clear guidelines to completely avoid ground and water contamination, and to ensure unauthorised entry to all types of stores. All of the above will finally ensure the phasing out of existing inhouse treatment facilities (within a period of 10 years) with a proper transition programme.

Also recommended is to gradually wean healthcare facilities away from managing inhouse treatment systems by identifying suitable central composting sites and outsourcing operation and maintenance of the facility to a competent third party.

In addition to making statistical analysis and recommendations, the intention of this survey was to develop a database of healthcare waste management enabling the Ministry of Health to make informed decisions in the future. Therefore, it is strongly suggested for the Ministry of Health to reach the balance healthcare facilities and establish a fully-fledged database which could be regularly updated for which purpose.

However, two hospitals, namely the Monaragala District Hospital and the Ashraff Memorial Base Hospital in Kalmunai have been identified as pilot projects due to their ability to develop efficient waste disposal methods and have been cited in the ‘Sustainable Healthcare Waste Management: Transforming Lives and Livelihoods in Sri Lanka’ project supported by the Ministry of Health and UNDP in Sri Lanka. This Report consists of methodology adopted results from the surveys undertaken, current management practices and its gaps, and outcomes from observation visits.

The Report was prepared by a consultant team led by Eng. Gamini Senanayake comprising Prof. Parakrama Karunaratne (Environment Expert), Dr. Cyril De Silva (Medical Expert), Eng. Ranjith Pathmasiri (Energy and Technology Expert) and Michael Cowing (International Consultant), supported by Chathuri Attanayake (Research Assistant) and Madupa Abeywardane (Project Assistant).

The consultant team worked under the guidance of the Technical Working Group headed by Dr. L.T. Gamlath – DDG, Environment, Health, Occupational Health & Food Safety, Ministry of Health until his retirement followed by Dr. V.T.S.K. Siriwardana – Director, Environment, Health, Occupational Health & Food Safety, Ministry of Health, other representatives of the Ministry of Health, Ajith Weerasundara – Director, Waste Management Division, Central Environment Authority, Dr. Buddika Hapuarachchi – Team Leader and Policy Specialist, UNDP, Dr. Virginie Mallawarachchi – National Professional Officer, WHO, Nilusha Patabandi – WASH Specialist, UNICEF under the overall supervision of Dr. Inoka Suraweera – Consultant Community Physician, Environmental and Occupational Health Directorate, Ministry of Health and Dr. Thusitha Sugathapala – University of Moratuwa as the Technical Advisor.