The objective of the debt standstill was to create some space for Sri Lanka to commence negotiations for restructuring debt in a manner that would enable debt service to resume in the future

The Finance Ministry in a statement said it has observed that there is a perception in society that the prevailing economic stabilisation in Sri Lanka is entirely due to external debt not being serviced, and that once debt service resumes, economic instability will return. It is also unfortunate to note that this same narrative is being used to trivialise and undermine the necessity for the critical macroeconomic reforms that are in fact the actual drivers of economic stabilisation. In this context the Finance Ministry via this statement addresses some of these misperceptions and explains the correct position in this regard to the public.

Is it correct that Sri Lanka does not service any of its foreign debt following the announcement of the debt standstill in April 2022?

It is incorrect to say that all foreign debt is not being repaid. The temporary moratorium on selected external debt service that was announced in April 2022 applied to external commercial debt and official bilateral debt. The Government continued to service multilateral debt as is the practice under the prevailing sovereign debt restructuring architecture.

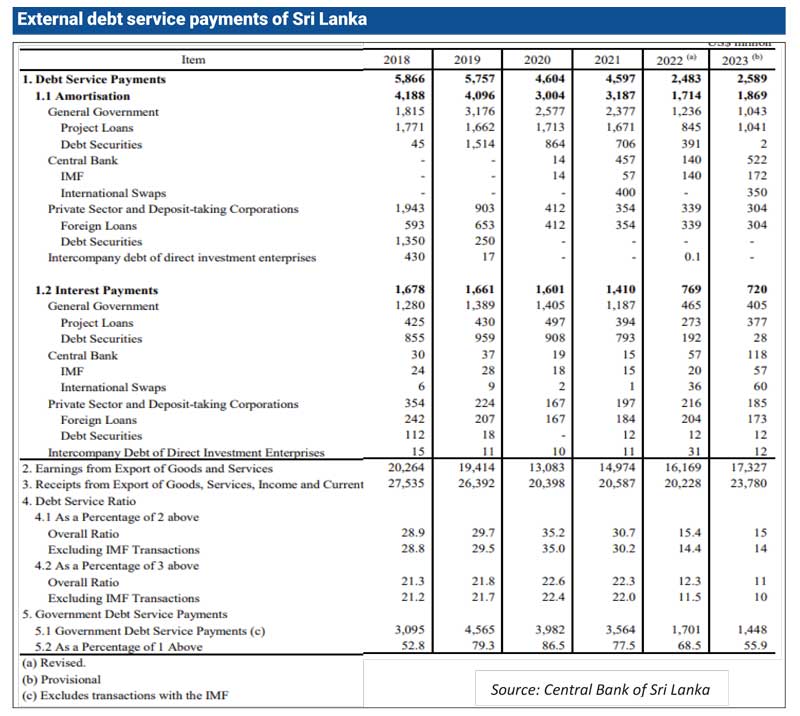

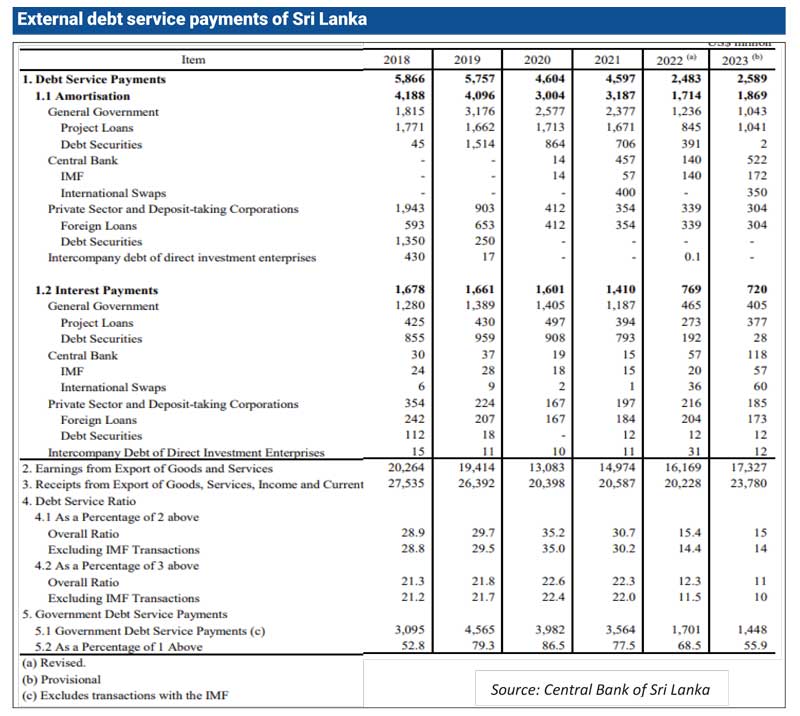

Accordingly, the Government continually serviced multilateral debt even after the April 2022 moratorium on selected external debt service. Considering the impact of debt service of the overall economy (including Central Bank, State banks, and private sector) on the balance of payments, in 2022 (including January to April) and 2023, Sri Lanka has made debt service payments of $ 2,483 million and $ 2,589 million, respectively as indicated in the given table. This amounts to approximately half of the usual debt service payments that Sri Lanka has made in a typical year prior to the announcement of debt standstill in April 2022.

What is the debt standstill and why was it announced?

The interim policy on servicing Sri Lanka’s external debt was announced on 12 April 20221. This entailed a temporary moratorium on servicing selected external debt, which included commercial and bilateral external debt denominated in foreign currency and governed by foreign country law2. Such a moratorium was required since Sri Lanka’s foreign exchange reserves had continually declined to the point that by early April 2022 usable reserves were at near zero levels.

“By the 11th of April, usable foreign currency reserves had dwindled to USD 24 million. The following week after the new year holidays, there was a debt service payment of USD 182 million on the 18th of April. The Central Bank also had short term commitments to pay for fuel, coal, and other essential imports amounting to over USD 500 million. Foreign currency debt repayments for the rest of the year 2022 amounted to USD 4.3 billion3.”

The objective of the debt standstill was to create some space for Sri Lanka to commence negotiations for restructuring debt in a manner that would enable debt service to resume in the future.

Therefore, there is a very important distinction between a temporary moratorium on external debt accompanied by a credible reform and debt restructuring plan, and simply halting debt service payments without a subsequent reform and restructuring roadmap. The former creates a path to stability and sustainability, whereas the latter would drive a country into deeper instability and eventual socio-economic collapse.

Is the prevailing economic stability simply because some external debt is not being serviced?

It is important to emphasise that simply not paying debt is not going to resolve the fundamental drivers of economic instability. Sri Lanka’s economic vulnerabilities and eventual deep economic crisis was due to a fundamental issue of solvency and not simply a liquidity crisis. A liquidity crisis can be addressed through additional external inflows (such as currency swaps/credit lines) or limiting external outflows (such as an external debt moratorium). This is a key misdiagnosis of Sri Lanka’s economic challenges. In order to solve a solvency crisis, it requires comprehensive macroeconomic reforms to address structural weaknesses in fiscal, monetary, exchange management, and debt management policy, which are the root causes of macroeconomic weakness which led to a sovereign debt crisis and related balance of payments crisis.

The failure to address these long neglected macroeconomic reforms would promptly be recognised by market actors who would immediately assign a very high risk to any transactions with Sri Lankan entities such as opening Letters of Credit. This would naturally preclude a return to normalcy of external inflows and outflows in the absence of macroeconomic reforms and a credible debt restructuring process.

From April 2022, Sri Lanka stopped paying selected external debt, but that did not instantly lead to the crisis being resolved by May 2022. In fact, the worst of the shortages were between May and August 2022. The foreign exchange crisis got worse until the country was able to demonstrate a clear and credible reform path, which was signalled by the Staff Level Agreement with the International Monetary Fund (IMF) in September 2022.

Subsequent to a debt moratorium, stability arises due to the confidence that is established by the reform measures taken by a government to address underlying solvency issues. Sri Lankan banks are today able to open Letters of Credit and engage in international trade finance even with a default sovereign credit rating because the global economic community believes that Sri Lanka’s current economic reform path will bring the country to a position of strength such that their counter-party payments will be honoured in the future. The value of Sri Lanka’s agreement with the IMF is that it is the key signal of that confidence to the global economy.

Similarly, a disruption to the IMF supported reform programme would generate an adverse signal that can easily unwind confidence in the economy and lead to a vicious cycle.

It is evident that the economic situation at present remains very delicate and there is no room for policy errors. Hence, careful management of the macro-fiscal operations is essential for Sri Lanka to preserve hard earned gains in managing the economy, create fiscal and external buffers in order to avoid falling into a similar crisis to that experienced in 2022, which had far reaching socio-economic consequences.

Is the debt standstill and the process of debt restructuring a case of “kicking the can down the road”?

Over several decades, Sri Lanka has accumulated a large of volume of public debt4. Repaying such debt in absolute terms requires either;

i) Generating a large annual budget surplus that can be used to settle debt on a net basis each year

ii) Divesting state assets converting this into cash that is used to settle past liabilities

The first option would incur a significant effort on the part of domestic taxpayers to generate revenue that exceeds total Government expenditure creating a surplus to settle debt. A budget surplus has been achieved only twice in Sri Lanka’s post-independence history (1954 and 1955). Even a primary budget surplus, where revenue exceeds expenditure excluding interest, has only been achieved on six occasions since independence. Sri Lanka has also not been successful in several recent attempts of divesting state enterprises and assets.

Accordingly, the pragmatic approach to addressing the country’s debt burden is to restructure debt in a manner that;

i) Creates time and space for the country to rebuild its fiscal and external buffers through capital grace periods

ii) Reduces the cash outflows through lower interest or coupon rates such that the restructured cash outflows are more easily accommodated with the foreign exchange inflows generated by the country

iii) Extends maturity of debt that gives time for the country to grow its economy such that the capacity to repay capital obligations is enhanced

iv) Reduces the magnitude of debt through nominal haircuts on outstanding capital.

A debt restructuring process entails a combination of the above mechanisms depending on the nature of different creditors, which results in material debt relief to the debtor country.

Finance Ministry....

Will economic stability be disrupted when there is an increase in post-restructuring debt service?

Sri Lanka has already concluded debt restructuring agreements with the official sectors5 and is in advanced stages of negotiations with external commercial creditors6. These agreements are expected to provide Sri Lanka with significant debt relief, and create the space required for the country to resume debt service obligations in a manner that does not disrupt economic stability in the future as well.

However, it is essential that Sri Lanka uses this time and space to diligently rebuild its fiscal and external buffers. If the country fails to do so, then a return to instability is possible. The IMF supported reform program is predicated on Sri Lanka reaching a Government revenue to GDP ratio of 15% by end 2025 and gross official external reserves are expected to reach $ 15 billion by 2028 (six months import coverage).

However, these buffers do not build themselves. It requires significant fiscal and monetary policy reform, which has to a great extent been front loaded in the IMF supported reform programme and has been supported by critical legal and institutional reforms, such as the Central Bank of Sri Lanka Act, Public Financial Management Act, and the Public Debt Management Act, and associated agency.

The reforms implemented thus far have enabled Government revenue to increase from 8.3% of GDP in 2022 to 11% of GDP in 2023 and it is on track to meet targets in 2024 as well. Similarly, foreign exchange reserves have increased to $ 6 billion (including the PBOC Swap arrangement with conditions on usability) from a position where usable reserves were at near zero levels in April 2022.

Similarly, it is necessary for the country to shift to an economic growth model that is focused on non-debt creating inflows such as exports of goods and services and foreign direct investment (FDI). This is crucial to generate the foreign exchange inflows that would be required to service external debt in a manner that does not disrupt stability. The legal and institutional framework to support the enhanced generation of non-debt creating inflows has also been established through the Economic Transformation Act (ETA) and its associated institutional structure.

Footnotes:

1Interim Debt Service Policy Announcement: https://www.treasury.gov.lk/api/file/54a19fda-b219-4dd4-91a7-b3e74b9cd683

2FAQ on interim debt service policy - https://www.treasury.gov.lk/api/file/1e2d4962-d635-4f77-9aa7-2f84ee385fed

3See page 61: https://www.treasury.gov.lk/api/file/ed037ac8-9727-4292-ae9b-edac08c7a314

4There have been past misconceptions on how debt has increased which has been addressed previously - https://www.treasury.gov.lk/api/file/f4890cb6-2bea-4763-a9f0-4034b62e420d

5Debt treatment agreements with the Official Creditor Committee and the Exim Bank of China - https://www.treasury.gov.lk/api/file/04ae6436-7921-453e-881f-bb3b107a461f

6Progress of restructuring of external commercial creditors - https://www.treasury.gov.lk/api/file/b0f5c1c0-9cd6-484e-8d00-8f6c7b7b0ba9