Saturday Mar 14, 2026

Saturday Mar 14, 2026

Thursday, 30 August 2018 00:00 - - {{hitsCtrl.values.hits}}

By Nimesha Dissanayaka and Manoj Thibbotuwawa

Most people use weather forecasts to plan their daily activities. However, for those whose livelihoods depend on variations in weather, this information becomes a lifeline. Farmers, as a community, are highly-sensitive to weather forecasts, as their agronomic decisions revolve around daily temperatures, rainfall patterns, and wind speeds.

Farmers used to be able to observe cloud patterns, behaviour of birds and animals, wind direction, and other natural occurrences to make accurate predictions about the weather. Before technology took over, farmers’ wealth of experience in agronomy helped them make spot-on weather forecasts.

However, traditional farming experiences and centuries worth of accumulated knowledge on weather have now become obsolete, thanks to climate change. While the importance of weather-related information is felt today, more than ever before, the consequences of inaccurate and untimely information are grave, causing farmers to make improper decisions and eventually lose their livelihood.

Thus, investing in climate information systems is a cost-effective way of making sure that farmers make the right agronomic decisions.

How do farmers access climate information?

Farmers use both traditional and modern sources to get climate information, such as weather reports (TV/radio/newspapers), kanna meetings, expert advice (from Agriculture Instructors at the Department of Agriculture), experience of other farmers, and local observations.

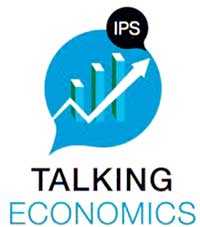

A survey carried out by the IPS in six districts (Anuradhapura, Batticaloa, Hambantota, Kurunegala, Badulla and Ratnapura), show that farmers most frequently use the experiences of other farmers, kanna meetings, and local observations to get climate information (Figure 1).

Before starting the cultivation season, kanna meetings inform farmers about the agronomic plans nd practices they should implement to suit prevalent weather patterns. Farmers blend this information with their local knowledge and peers’ experiences when making their own plans.

The moderate use of weather reports and the low usage of mobile weather alerts and applications indicate that farmers in Sri Lanka prefer conventional methods when it comes to receiving climate information.

Role of ICT in climate information dissemination

Long term (seasonal), medium term, and short term weather forecasts help farmers plan ways to maximise crop productivity. Most critical farming decisions are based on long term/seasonal forecasts, where farmers decide which mix of crops and seed varieties to plant, purchase seed and inputs, and prepare land accordingly.

While kanna meetings can still be useful in providing long term forecasts, peer experiences and local observations have become unreliable due to frequent changes in the climate.

Medium term climate information and short term forecasts help determine the timings of various farming activities, such as sowing, weeding, spraying, and harvesting. However, the three widely used information sources (peer experiences, kanna meetings, and local observations) are hardly useful in providing medium and short term information. Here, information communication technologies (ICT) can play a major role in bridging the gap in information delivery.

According to Professor Klaus Schwab, the Founder and Executive Chairman of the World Economic Forum, rapid evolution and uptake of digital technologies, hailed as the Fourth Industrial Revolution, have the potential to improve the quality of life for everyone, including those in the agriculture sector.

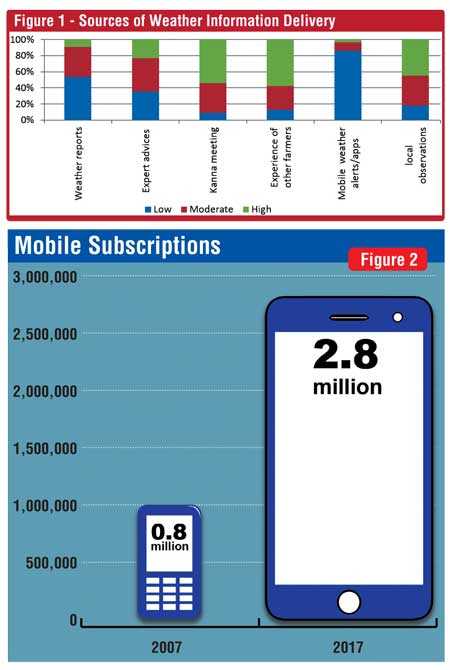

Sri Lanka too is making use of these technologies; the total number of mobile phone connections in the country increased more than three-fold, from 0.8 million in 2007, to 2.8 million in 2017 (Figure 2). Thus, the ICT sector has the potential to be an important player in strengthening climate information systems. It can provide short, medium, and long term climate forecasts, as well as information on crop varieties and farming techniques that reduce the impacts of climatic variations and withstand extreme weather conditions.

Radios and mobile phones are the most popular ICT tools used to disseminate climate information. While radios have wider coverage and higher comprehensiveness than mobile phones, the former does not have a direct link with the user. Therefore, SMS is the most cost effective and simplest way to deliver information. Users with smart phones can have access to more advanced visual advices and more enhanced content. Moreover, mobile forecasts have the potential to target users geographically.

Challenges of using mobile phones for climate information delivery

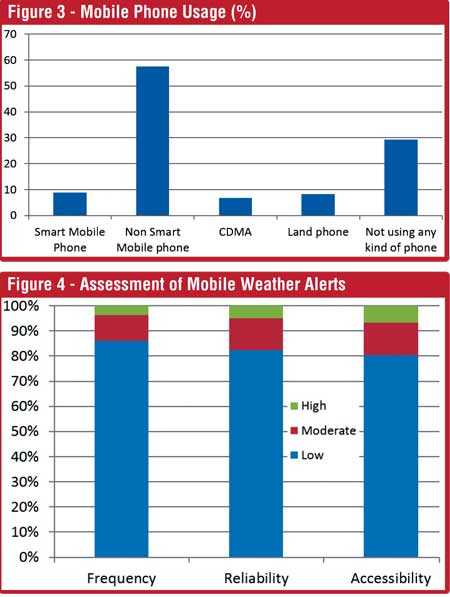

The IPS survey indicates that, despite significantly high mobile phone usage and penetration in Sri Lanka, acclimatising farmers to use phones to access climate information remains a challenge. While more than a half of the farmers have access to mobile phones, over 29% of farmers do not use any kind of phone. Moreover, only about 9% of farmers have access to a smart phone. This might be partly due to regional disparities in mobile penetration in Sri Lanka.

The IPS survey also finds that farmers hardly use mobile weather alerts. This is due to the unreliability and inaccessibility of mobile weather alerts (Figure 4). The farmers’ inability to understand highly technical climate information can also play a part in this regard.

Way forward

Despite various challenges, mobile phones have the potential to become a major component in climate and weather information systems. For best results, instead of providing weather information as a stand-alone service, it should bundled with other complementary information, such as customised crop guidance, market/price information, or even as a package with index insurance schemes. For example, in India, the Farm Need app provides information on agronomic management practices and weather related risks for selected crops.

Also, the information delivered through the mobile channels should be based on the needs of the users. The communication tools should be targeted to suit both the information and the users. It is also important to develop mobile platforms that facilitate two-way information flows, so that the collection of localised data and feedback from farmers can be done simultaneously. An example is Uganda’s Mobile Weather Alert system.

With increased mobile penetration and technical knowledge among rural farmers, mobile phones can be used as a potential solution to existing challenges in climate information delivery.

[Manoj Thobbotuwawa is a Research Fellow and Nimesha Dissanayaka is a Research Assistant at the Institute of Policy Studies of Sri Lanka (IPS).]