Sunday Feb 22, 2026

Sunday Feb 22, 2026

Thursday, 24 March 2022 01:15 - - {{hitsCtrl.values.hits}}

The Government is also seeking to resolve the current shortage of diesel to avoid a protracted impact on exports and GDP. For decades, Sri Lanka has had twin deficits – a fiscal deficit and a deficit on the current account of the balance of payments

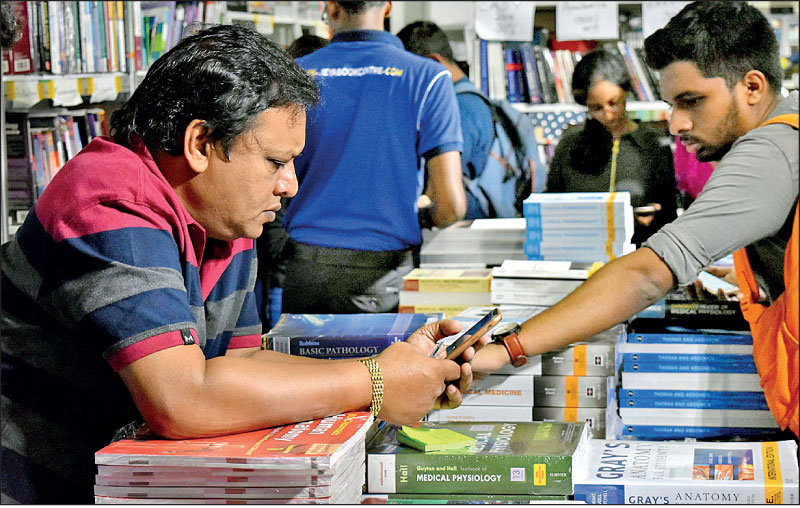

Digital services are becoming increasingly important in Sri Lanka

|

By Faris Hadad-Zervos and Hans Timmer

By Faris Hadad-Zervos and Hans Timmer

Sri Lanka has managed the health and safety aspects of the COVID-19 pandemic in a commendable way. The nation has been and continues to be swift in safeguarding the health of its population, including vaccinating its citizens. However, the devastating economic impacts of the pandemic are far from over.

Across South Asian countries, global and local supply disruptions caused by the COVID-19 pandemic have created colossal macroeconomic challenges. Rising energy and food prices are fuelling inflation and magnifying import bills. Relief efforts and reduced tax revenues have worsened fiscal balances.

Deteriorated balance sheets in the private sector have created financial sector vulnerabilities that are easily underestimated because short-term support measures by central banks have so far masked the weakening structure of many beneficiary firms.

Underneath the challenging macroeconomic environment, considerable inequalities have emerged. Workers in informal sectors, most of whom are in precarious employment arrangements, have been hit hardest by the pandemic while hardly being protected by social support systems.

Indeed, the pandemic has left real scars on Sri Lanka’s economy. Tourism has been hit hard, with only a few buffers to react, and it is still only half of what the industry was two years ago. The transportation sector is still operating at 14% below its capacity before the pandemic and the remaining shortfall in the accommodation sector is at 54% despite recent promising trends.

The Government is also seeking to resolve the current shortage of diesel to avoid a protracted impact on exports and GDP. For decades, Sri Lanka has had twin deficits – a fiscal deficit and a deficit on the current account of the balance of payments. Year-on-year inflation has now reached 15% and debt service has become challenging.

There are no easy solutions to these challenges under present circumstances. Firefighting measures like import restrictions and price controls, meant to provide short-term relief, are at a risk of backfiring as they reinforce supply distortions and undermine confidence.

However, while solutions are not easy, they are not impossible – with will and widespread support. The balance of payments can be stabilised with international coordination. And it is not the first time that countries would have emerged stronger from a crisis: Sri Lanka’s telecom sector is already producing 32% more than before the pandemic, its information-technology sector has expanded by 20%, and the financial services sector by 28%. Seen from this perspective of a clear expansion in digital technologies and services, the future of Sri Lanka looks quite promising.

Driving inclusive development with digital technologies

This fast growth of the digital services sectors in Sri Lanka – despite the pandemic – reflects a general trend of the rising importance of digital services: they are increasingly internationally tradable and are becoming the main source of productivity increase in other sectors. The good news is, Sri Lanka has a comparative advantage in these sectors and is well poised to turn them into a strong growth engine.

After all, services within Sri Lanka are already larger as a percent of GDP than in other South Asian countries and the country has the highest share of service workers in manufacturing. Sri Lanka also has the highest human capital index in South Asia, an important factor, as the production of digital services requires skilled workers.

And digital technologies will provide youth – comprising around 24% of the country – with business opportunities either in digital services or in sectors that get market access through them.

Notably, the new services economy can generate growth in exports and GDP and perpetuate inclusive growth. Currently, almost half of the workers in Sri Lanka’s services sectors are female. Therefore, the growth of services can contribute further to gender equality.

Digital services can also unleash the underutilised potential in the informal sector. The gig and sharing economy, an outcome of advancement in technology and flexible jobs, fit the flexible and small-scale characteristics of the informal sector. Digital platforms such as Odesk and PickMe provide small firms access to markets and digital payment systems bring financial inclusion.

To create a sustainable development path, inclusion is as important as growth itself.

However, key reforms are needed to fully enable inclusive development: (1) constraints that small firms experience when they want to access digital services must be addressed; (2) digital platforms require appropriate regulation; and (3) trade barriers in services should be lowered.

The time for reform is now. However, existing macroeconomic imbalances outlined above can frustrate the development of new production potential. That’s why macroeconomic stabilisation is an essential part of generating inclusive growth.

As Sri Lanka stabilises the balance of payments, it is critical to keep an eye on the long-term reward of developing new potential, especially in the informal sector. With concerted efforts, a more robust and inclusive economy is within reach of Sri Lanka. The nation is poised to turn challenge into opportunity, emerging stronger and ultimately victorious in the COVID-19 crisis.

(Faris Hadad-Zervos is the World Bank Country Director for Maldives, Nepal and Sri Lanka, and Hans Timmer is the Chief Economist South Asia at World Bank.)