Tuesday Mar 04, 2025

Tuesday Mar 04, 2025

Tuesday, 27 March 2018 00:00 - - {{hitsCtrl.values.hits}}

By Eshini Ekanayake

GDP growth in 2017 came in at 3.1% down from 4.5% in the previous year

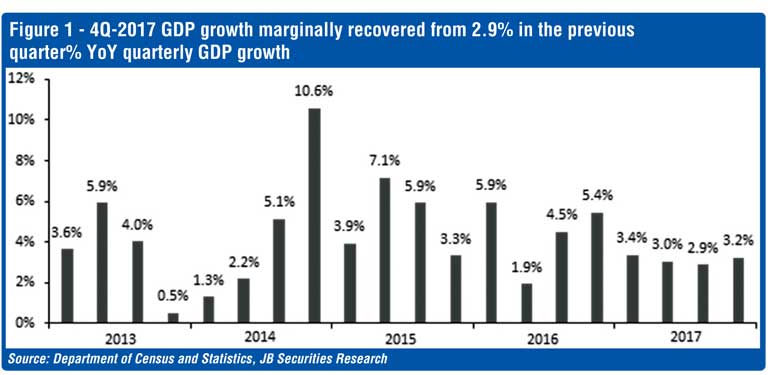

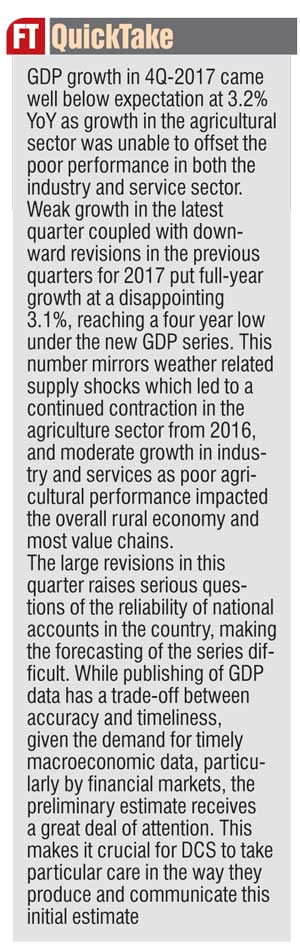

GDP growth in 4Q-2017 came in at 3.2% YoY, marginally recovering from the low of 2.9% in the previous quarter. This brings annual real GDP growth for 2017 to a four year low of 3.1% (under the new GDP series) from 4.5% in the previous year which was revised up from 4.4%, coming well below consensus expectations: CBSL, IMF, and the World Bank put growth at 4.0%, 4.2%, and 4.6% respectively (Figure 1).

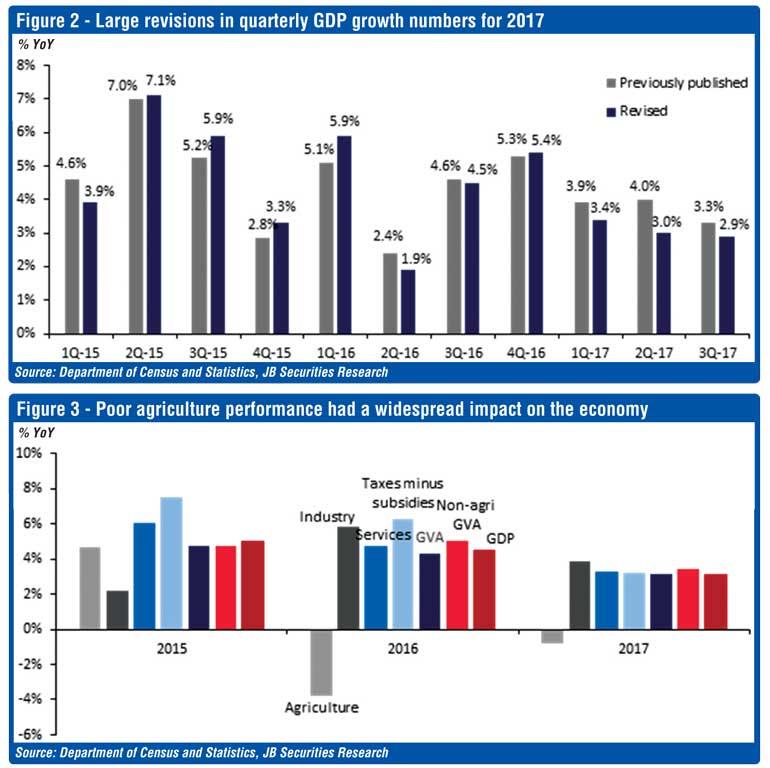

The Department of Census and Statistics (DCS) that is responsible for compiling national accounts in the country originally released the GDP data with a GDP print of 1.4% YoY for 4Q-2017 which was later withdrawn. According to the Director General of the DCS, several data sets used in the compilation of GDP was received close to the date of release and due do the annual revisions of both 2015 and 2016 that happen with the release of 4Q-2017, the data was withdrawn for recalculating and recompiling purposes. However, despite the upward revision in the 4Q-2017 print the full year GDP print for 2017 remained roughly the same (3.2% YoY vs. 3.1% in the initial release)as there were substantial downward revisions of GDP growth for the prior three quarters, which partly reflects quarterly upward revisions in 2016 (Figure 2).

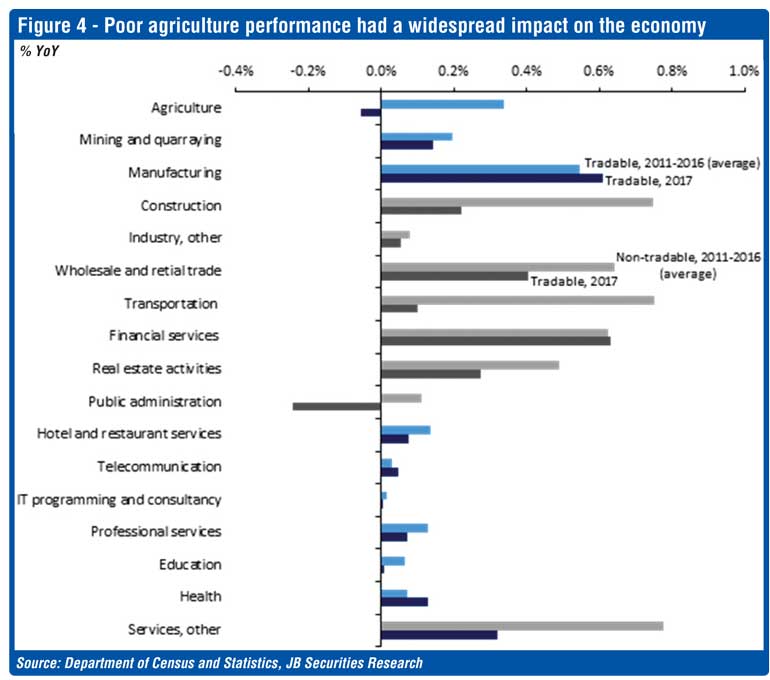

The poor growth performance in 2017 was driven by a continued contraction in the agriculture sector for the second year as a result of the prolonged drought since early 2016, and heavy floods in mid-2017 (Figure 3). The weather-related shocks which were largely felt in the rural economy also had a widespread impact on overall economy activity as certain industries and services use agri-inputs for value addition.

In the case of coconuts, it is only the farming of coconuts that is classified under the agriculture sector, whereas the value addition activities that transform it to oil such as the manufacturing process, packaging, labelling, storing, transporting, and retailing are classified in the industry and services sector. This is suggestive in the breakdown of the data where Gross Value Added (GVA) grew by 3.1% in 2017 where as non-agri GVA managed to grow only slightly better at 3.4%.

Typically, a slow-down in the economy caused by a supply shock warrants support from the government, however there was limited fiscal space to support growth given that the government is aiming to reduce its fiscal deficit to 3.5% of GDP by 2020 under the terms of its IMF-EFF programme. The contraction in ‘public administration, defence and social security’ services of 4.8% is indicative of this. In addition, a higher tax environment and tight monetary policy which led to moderate private sector credit growth of 14.7% were likely causal factors for reduced economic activity.

Other key takeaways from 2017 GDP data

DCS needs to balance the trade-off between accuracy and timeliness of GDP data

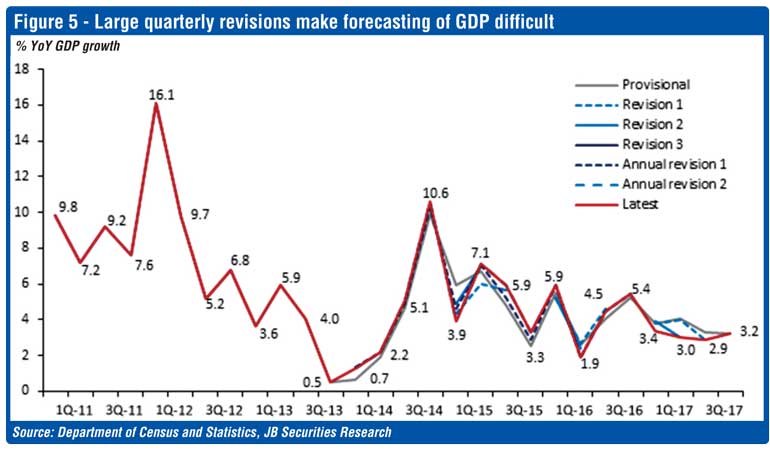

The large revisions in this quarter raises serious questions of the reliability of national accounts in the country, making the forecasting of the series difficult (Figure 5). DCS claims that these revisions are essential due to the time lag in getting the final data from certain institutions. As such, preliminary estimates are published largely based on partial output information and then revised up to two years each time the initial estimate for 4Q GDP is released.

While revisions do signal improvements in the quality of the data, the long delay taken to do so is fairly an uncommon practice amongst other countries. Most countries publish preliminary estimates a few weeks after the end of the quarter with second and third estimates published one or two months later. These estimates are then further refined annually. To DCS’s credit though, empirical evidence suggests that GDP revisions are generally larger in economies which are growing at rates substantially different from normal, as is currently the case for Sri Lanka which suffered from a negative supply shock.

When publishing any form of macroeconomic data there is a trade-off between accuracy and timeliness, and the consequence is that these data points sometimes need to be revised. However, given the demand for timely macroeconomic data, particularly by financial markets, the preliminary estimate receives a great deal of attention as it provides the first signal on the performance of the country’s real economy. This makes it crucial for DCS to take particular care in the way they produce and communicate this initial estimate.

(The writer is Economist, JB Securities and can be reached via [email protected];+94 112 490 932.)

Discover Kapruka, the leading online shopping platform in Sri Lanka, where you can conveniently send Gifts and Flowers to your loved ones for any event including Valentine ’s Day. Explore a wide range of popular Shopping Categories on Kapruka, including Toys, Groceries, Electronics, Birthday Cakes, Fruits, Chocolates, Flower Bouquets, Clothing, Watches, Lingerie, Gift Sets and Jewellery. Also if you’re interested in selling with Kapruka, Partner Central by Kapruka is the best solution to start with. Moreover, through Kapruka Global Shop, you can also enjoy the convenience of purchasing products from renowned platforms like Amazon and eBay and have them delivered to Sri Lanka.

Discover Kapruka, the leading online shopping platform in Sri Lanka, where you can conveniently send Gifts and Flowers to your loved ones for any event including Valentine ’s Day. Explore a wide range of popular Shopping Categories on Kapruka, including Toys, Groceries, Electronics, Birthday Cakes, Fruits, Chocolates, Flower Bouquets, Clothing, Watches, Lingerie, Gift Sets and Jewellery. Also if you’re interested in selling with Kapruka, Partner Central by Kapruka is the best solution to start with. Moreover, through Kapruka Global Shop, you can also enjoy the convenience of purchasing products from renowned platforms like Amazon and eBay and have them delivered to Sri Lanka.