Tuesday Feb 24, 2026

Tuesday Feb 24, 2026

Saturday, 12 November 2022 00:05 - - {{hitsCtrl.values.hits}}

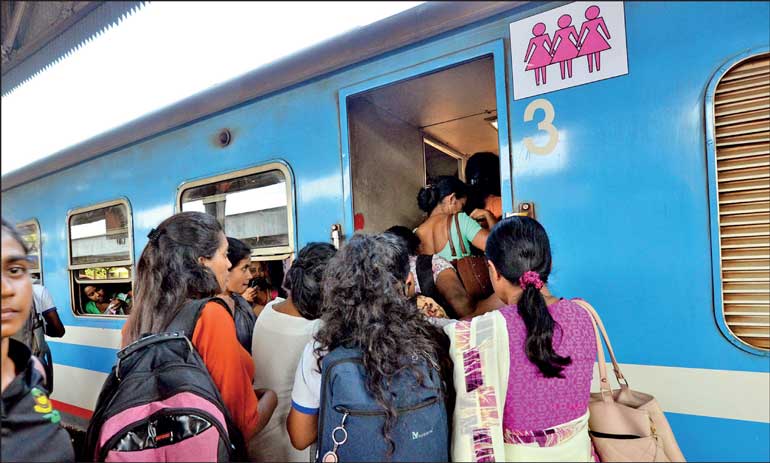

Working class women cannot be made to pay for the ‘odious debt’ generated by the recklessness and corruption of (almost entirely male) Sri Lankan political elites – Pic by Shehan Gunasekara

Backdrop

Countless images of women carers flitted through April-July 2022 on Sri Lankan television screens, social media, and newspapers. Carers with young children, mothers with new-borns leaving them with equally young children while they stood in queue for gas or kerosene, children doing their homework on tuk-tuks while their parents got in line for petrol and diesel. Yet, Sri Lankan policy pronouncements rarely mention working-class women. In a country where women comprise 52% of the population, this is astounding. Especially so when the dominant three foreign exchange earners for the country – garments, tea exports and migrant workers to the Middle East – rest on the efforts of women workers.

In the current response to Sri Lanka’s debt crisis, the voices and needs of working-class women are once again being ignored by policymakers, despite the evidence all-around of women intensifying their unpaid labour even as the conditions under which they perform paid labour deteriorate.

As feminist economists, our argument is straightforward: debt justice is a feminist value and principle. And at the core of our understanding of debt justice is the principle that working class women cannot be made to pay for the ‘odious debt’ generated by the recklessness and corruption of (almost entirely male) Sri Lankan political elites.

Local corruption, global debt crisis

This latest round of ‘odious debt’ in Sri Lanka was created by an authoritarian and corrupt government, led by a President who initially fled the country rather than take responsibility for the economic catastrophe he unleashed. If the Pandora papers are anything to go by, a former President and an entire corrupt family clearly accumulated personal wealth at the expense of Sri Lankan people. This is an economic catastrophe that was enabled and facilitated by highly paid financiers at places like Blackrock and other private investment firms, which now hold almost 35% of Sri Lankan external debt. Their windfall profits during a global pandemic indicate the extent to which they have profited at a time of human misery.

Is there are a need to be anxious about financial vulnerability of these investment firms? Clearly not, given their extremely healthy balance sheets. Or, perhaps, we need to worry that Sri Lanka may not be able access credit markets again? No need, it appears. Jerome Roos in his book Why Not Default? The Political Economy of Sovereign Debt, argues that not only has debt default been the norm in the pre-1980s period, defaulted countries, when they have borrowed afterwards, their terms have been no different from non-defaulting nations.

We must, however, worry about the vulnerability of the working-class people, and particularly the women, of Sri Lanka. Across the global South, the pressures of survival work – or the work of social reproduction – amidst a pandemic that dried up sources of livelihood has fallen upon women. It is unconscionable to insist on austerity and call for privatisation softened by only by a piffle of cash transfers at a time when women and their families are trying their hardest to recover from those difficult times and fighting rampant inflation. As feminist economist Jayati Ghosh points out, particularly in this case of ‘odious’ debt, the current proposals prioritising so-called re-entry into finance markets are proposals to effectively bail out private finance (both local and global) and let corrupt elites get away by putting the burden on the workers, and especially women workers - both paid and unpaid – of Sri Lanka.

These proposals do not pass the basic test of feminist debt justice. Sri Lanka’s Feminist Collective for Economic Justice has issued statement after statement recording the difficulties faced by working class women and the care burden they carry. However, based on the silence from the Central Bank of Sri Lanka and economic think tanks at the forefront of negotiations with the IMF, they remain oblivious to the needs of 52% of Sri Lankans.

Women’s labour force participation is not the same as justice for women

There is one area in which policy analysts do tend to mention women – when they repeatedly talk about the need to increase female labour force participation (FLFP). We have also seen private financial giants like BlackRock claim feminist credentials by similarly emphasising women’s “right to paid work” (and participation in markets more generally). Sri Lanka’s FLFP did fall by 10% over the last three decades and is now stagnant at 31% according to the World Bank (2021), creating one of the largest gender gaps in labour force participation in the world. By the measure that pro-market policymakers claim to care most about, the policies of the past few decades have failed Sri Lankan women. However, this emphasis on labour force participation alone ignores are both the deep linkages between unpaid and paid work, as well as the troubling implications of increased access to labour markets when those markets only provide under-paid work under sub-standard labouring conditions.

On 23 August 2022, the UNDP-Sri Lanka announced that it had launched a facility to work with and assist private sector corporates to partner and contribute towards humanitarian efforts due to the debt crisis. It is as if the UNDP is unaware of the absence of living wages in the tea, garments, and tourism sectors of their corporate partners, as documented by countless feminist scholars of Sri Lanka It is the lack of a living wages which propels Sri Lankan women workers and families to seek soup kitchens and mutual aid initiatives in the first place. There nothing ethical or feminist about creating economic conditions that force women into indecent jobs, intensifying their double burdens and keeping them in place with poverty wages.

Gendered responses

Our solidarity with Sri Lankan women workers comes from our acute sense that Sri Lanka is a canary in the coal mine. We can see Pakistan’s vulnerability, as well as that of Bangladesh; we can see the difficulties the RBI is having propping up the value of the rupee; a recent UNPD report puts over 50 developing countries at acute risk of default. We cannot allow another 1980s-style debt crisis to unfold across the developing world, facilitated and enabled once again by the IMF. After all, those who forget history are doomed to repeat it. The fact that this debate about debt restructuring is being rehashed in Sri Lanka for the 17th time defies all reason. It is truly past time that we stopped resurrecting the zombie of austerity and stop creating moral hazard conditions under which private lenders can assume that they are going to be bailed out for their mistakes by working class women and men.

What do we propose? From that vantage point, here are some propositions that we ask Sri Lankan policymakers and advisors to consider:

1). Debt is a global crisis today. The UN identifies 54 developing economies with severe debt problems after a surge of borrowing to respond to the pandemic played a key role in exacerbating debt distress. Total debt in the developing world now stands at a 50-year high. In middle-income countries, sovereign debt stands at a 30-year high, with sovereign debt distress more than doubling in the first six months of 2022. The implication is that we are facing the greatest wave of debt crises and defaults in developing economies in a generation.

2). The G20’s Debt Service Suspension Initiative, which suspended debt payments for 73 low-income countries, was terminated at the end of 2021. Sri Lanka’s policymakers should unite with other indebted countries to reinstate G20s Debt Service Suspension Initiative. While this will not provide a structural solution to the debt crisis, it is a minimal effort toward creating some temporary fiscal space in the context of record high inflation.

3). Centre all proposals upon the principle that private creditors must participate on equivalent terms in debt restructuring and burden sharing.

4). Recognise that middle-income countries, where the vast majority of the world’s poor reside and where serious debt defaults are taking place, must be included in the Common Framework for Debt Treatment. Out of the three countries that have so far asked for their debt to be treated within this framework – Chad, Ethiopia, and Zambia – only Zambia has seen some forward movement.

5). Call for a transparent and binding debt workout mechanism within a multilateral framework for debt crisis resolution. Such a mechanism would address illegitimate debt and provide systematic, timely and fair restructuring of sovereign debt, including debt cancellation, in a process convening all creditors. The UN General Assembly has adopted multiple resolutions calling for such a mechanism over the years.

6). Debts unpayable by any country need to be cancelled. Debt justice movements across the developing world have urged for the cancellation of all unsustainable and illegitimate debts in a manner that is ambitious, unconditional, and without carrying repercussions for future market access. Past cases show how reducing debt stock and debt payments allow for countries to increase their public financing for urgent domestic needs.

7). The IMF’s Debt Sustainability Analysis (DSA), which measures sovereign vulnerability to sovereign debt stress, must incorporate SDG financing needs, climate vulnerabilities as well as human rights and gender equality commitments into its methodology. Such an integration widens the methodology of DSAs from narrow economic considerations of a country’s ability to pay its creditors without accounting for how servicing debt may undermine its ability to meet the needs of its people, environment, and international human rights obligations.

8). Finally, an automatic mechanism for a debt standstill in the wake of an extreme exogenous shock should be created. As proposed by the G77 group of developing countries in the UN General Assembly in response to the global financial crisis of 2007-8, “an automatic mechanism for a debt payments moratorium can be established for a determined period in response to external catastrophe events, as climate and natural disasters, health pandemic, military conflict and inflation.” The prescience of the G77 group in 2009 offers a salient message as we recover from a global pandemic and remain amid multiple crises of war, inflation, and global monetary tightening.

The principle of burden-sharing ensures genuine debt relief, as does the commitment to include all creditors, bilateral, multilateral, and private, in an automatic or orderly way. This avoids extra costs caused by lengthy defaults and delays in restructuring and generates a mutual trust that is desperately in need to bolster the international debt architecture. Recognising that multilateral institutions account for around one-third of the outstanding debt of low- and lower-middle-income countries, the World Bank and IMF must participate in such efforts. They should both cancel debt payments owed, and the IMF should eliminate surcharges. Protection needs to be provided to debtor states against holdouts and lawsuits by non-participating creditors, while laws and procedures for responsible borrowing and lending need to be ensured to protect citizens and communities, and working women, in particular, against corrupt, predatory, and odious debts.

(Kanchana N. Ruwanpura is Professor of Development Geography at the University of Gothenburg, Sweden. Bhumika Muchhala is Senior Policy Analyst at the Third World Network and New School University, USA. Smriti Rao is Professor of Economics at Assumption University, USA.)