Wednesday Feb 18, 2026

Wednesday Feb 18, 2026

Tuesday, 11 February 2020 00:28 - - {{hitsCtrl.values.hits}}

Sri Lanka appears to do relatively well in terms of gender representation in STEM education but significant gender differences in enrolments exist within this segment – Pic by Shehan Gunasekara

|

| By Ashani Abayasekara |

Sri Lanka is well recognised as a leader in gender-equal education in the developing world; World Bank statistics show that primary and secondary school enrolments and completion rates are similar for girls and boys, while girls have higher enrolment and retention rates in upper secondary and tertiary education.

Sri Lanka also appears to do relatively well in terms of gender representation in the broad field of science, technology, engineering, and mathematics (STEM) education.

For instance, according to the University Grants Commission (UGC), females accounted for nearly half – or 49% – of undergraduate enrolments in STEM subjects in local universities in 2017, in comparison to a global figure of 35%. Girls also do better than boys at school and university exams in general, and available evidence at the early stages of education suggests that girls outperform boys in mathematics and science. That said, significant gender differences in enrolments exist within STEM fields, which this blog aims to shed some light on, and discuss possible reasons and solutions. A failure to sustain initial educational advantages in key STEM fields in higher education (and employment) indicates that there is a large pool of unutilised intellect and creativity. This is both a waste of human capital and of government investments in free education.

Sri Lanka is also experiencing a current labour shortage in several areas including science and technology, highlighting the importance of attracting capable individuals, including females who account for 54% of the 18 and above population, into such fields.

Moreover, in the context of an upcoming technology-driven Fourth Industrial Revolution, being equipped with STEM-related skills will be increasingly important to survive in the future labour market; in line with international evidence, recent research shows that, in Sri Lanka too, science and engineering professionals are some of the least vulnerable to computerisation.

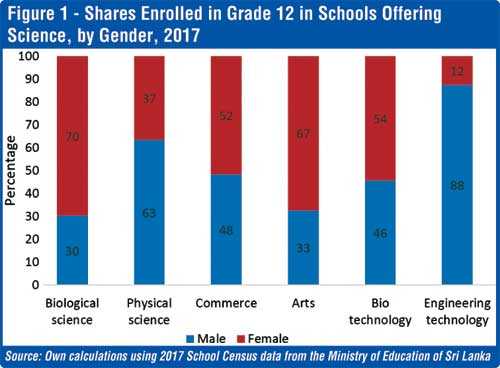

As Figures 1 and 2 indicate, while girls outnumber boys in both school and university enrolments in the biological sciences, there are far more boys in the physical sciences and related fields. Figure 1 shows that, among students enrolled in Sri Lankan public schools offering science education in higher grades, girls account for 70% in the biological sciences stream – a share even above that of the arts stream, a field typically associated with females –, but for only 37% in physical sciences and a mere 12% in engineering technology.

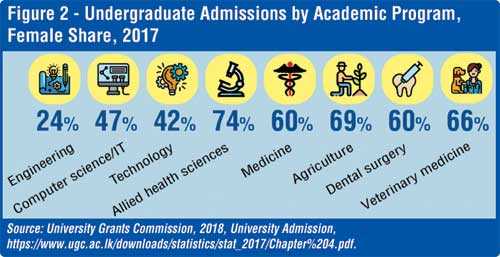

Similarly, at the undergraduate level, compared to the 74% of females enrolled in the allied health science program and the 60% in medicine, only 24% are enrolled in engineering, while those in technology and computer science also remain below 50%.

Moreover, consistent with trends in other countries, girls’ representation in STEM even in the biological sciences, falls further at the graduate level; UGC statistics indicate that the female shares of those completing a Bachelors degree in science falls to 60%, and to a further 42% at the post-graduate degree level, while the percentage of female engineering graduates remains in the 20s at the graduate and post-graduate levels.

While the overall low numbers of students pursuing STEM subjects in Sri Lanka has been attributed to limited opportunities – with only 10% of public schools offering STEM education at the collegiate level – and to a shortage of qualified and experienced teachers, there is limited research looking into reasons behind large gender differences in the uptake of different STEM subjects.

Evidence from a range of countries points to several factors that contribute towards female underrepresentation in physical science subjects, including;

(1) negative stereotypes about girls’ competencies in subjects like mathematics, engineering, and IT, which can lower exam performance as well as aspirations for engineering and other physical science-related careers over time;

(2) social, cultural, and gender norms, where girls are compelled to assess their mathematical competencies lower than boys with similar mathematical performance, and to hold themselves to a higher standard than boys, believing that they have to be extraordinary to succeed in so-called “male” fields;

(3) a significant male advantage in cognitive abilities in the area of spatial skills – viewed as important for success in engineering and related fields – although recent advances in girls’ performance in mathematical subjects have challenged this argument; and

(4) lower job prospects for female engineers, with society judging women as less competent than men in “male” jobs and considering women successful in “masculine” jobs less likable.

Distinguishing between cognitive and cultural factors that drive female underrepresentation in the physical sciences and other STEM fields is necessary to develop specific measures to address the problem.

In terms of cultural factors, international evidence calls for breaking down stereotypes and biases. Encouraging more girls and women to enter physical science fields will require changing classroom and work spaces. For example, creating an environment that promotes a “growth mindset”, with positive feedback and encouragement from teachers and parents, can enhance girls’ self-esteem, and in turn improve their performance and aspirations.

With regard to cognitive differences such as spatial skills, research suggests that such skills can improve significantly within a short period of time via simple training courses. As such,  ensuring that girls are raised in environments that complement their achievements in mathematics with spatial skills training is important to build competencies as well as to bolster their confidence to consider a future in a STEM field, not only limited to biological sciences. One cannot, however, simply assume that such measures will work for Sri Lanka; a first priority for Sri Lanka is to conduct in-depth research into specific barriers at the individual, family and peer, school, university and societal levels, to identify the types and nature of existing constraints that deter girls’ participation in engineering and other physical science related subjects, particularly compared to the biological sciences. For instance, the fact that girls outperform boys in mathematics in school, implies that cultural and environmental factors might be more responsible for observed underrepresentation.

ensuring that girls are raised in environments that complement their achievements in mathematics with spatial skills training is important to build competencies as well as to bolster their confidence to consider a future in a STEM field, not only limited to biological sciences. One cannot, however, simply assume that such measures will work for Sri Lanka; a first priority for Sri Lanka is to conduct in-depth research into specific barriers at the individual, family and peer, school, university and societal levels, to identify the types and nature of existing constraints that deter girls’ participation in engineering and other physical science related subjects, particularly compared to the biological sciences. For instance, the fact that girls outperform boys in mathematics in school, implies that cultural and environmental factors might be more responsible for observed underrepresentation.

Upon identifying the status quo in terms of specific barriers, international best practices can be drawn upon, in line with the local context, to develop potential measures to increase female representation and active participation in traditionally male-dominated STEM fields.

[Ashani Abayasekara is a Research Economist at the Institute of Policy Studies of Sri Lanka (IPS). To talk to the author, email [email protected]. To view this article online and to share your comments, visit the IPS Blog ‘Talking Economics’ – http://www.ips.lk/talkingeconomics/]