Monday Feb 16, 2026

Monday Feb 16, 2026

Saturday, 18 August 2018 00:00 - - {{hitsCtrl.values.hits}}

There is sufficient evidence to show that the quality of life of the people has not improved even with the loans and

massive debts obtained to develop the economy – Pic by Shehan Gunasekara

By Jayampathy Molligoda

Historical background

One of the objectives of the open economic policy as articulated by President J.R Jayewardene in 1977 was to have an export-led growth strategy and to accelerate international trade and investments. This would enable the country to eventually have a positive trade balance (exports to exceed imports) and a surplus in the current account of the Balance of Payments.

According to Central Bank reports, since 1977 there had been not a single year with a positive trade balance. Also, there was always a deficit even in the current account of the Balance of Payments. One can therefore argue that the implementation of the open economy, even after shifting to a model based on socially-oriented market economy (adopted since early ’90s) did not achieve desired results during the last 40 years up to date. Instead, it has created social unrest among the less-privileged people in the country.

There is sufficient evidence to show that the quality of life of the people has not improved even with the loans and massive debts obtained to develop the economy under these economic policies. According to the World Bank development reports, 45% of our population is below “5$ a day” which is one of the generally accepted international criterion.

As can be seen from the ‘HIES’ undertaken by Department of Census and Statistics, over 51% of the national income is enjoyed by the 20% of the higher income earning category(rich) of the people whereas, only 5% of the income is accrued to the 20% of the population(poor) in the lower income category. As per HIES (2016), the average monthly household income in the poorest 20% was Rs. 14,843 and richest 20% was Rs. 158,072.

Sri Lanka’s economic growth since 1960

One of the key parameters of assessing the economic progress is to measure the growth of the economy in terms of real increase of the Gross Domestic Product (constant rupee). In fact, the main objective of transforming the economy into open market policies was to achieve a rapid economic growth. The measurement of economic performance using GDP growth rate has its limitations and therefore should not be taken as the sole criteria in evaluating the economic development.

It can be seen that there have been no significant increases in the growth rates even after adopting mixed economic system, open market and social market economic policies. Also, there had been ups and downs if we take annual changes. For example, the higher growth rate of 9.1% was achieved in 2012 and the rates of 8.2% was achieved in the years 1968 and 1978. The lowest of -1.5% was recorded in 2001. The per capita income in 2017 was $ 4,065, still below comparable developing economies.

The trade deficit was $ 9,619 million. The external debt as a% of GDP in 1977 was only 21% and now it’s 60%. The government ‘budget deficit’ has become a recurrent feature since independence.

To understand what went wrong, many studies have been undertaken by eminent scholars and academics in order to critically evaluate the practical implementation of the concept of neo-liberal economic system and how it works in the developing countries. The proponents argue that the best way to help the poor is to make the economy grow and allow the market to decide major economic policies/activities whilst addressing market failures. They also believe that trade liberalisation would enhance a country’s income by forcing resources to move from less productive uses to more productive uses.

However, one can argue that, what actually happened was that most of the so-called ‘inefficient industries’ and other agricultural or “service’ sector ventures had to close down under pressure from international competition. It had destroyed existing jobs but no new job opportunities in the so-called ‘productive ventures’ were created. This is due to the fact that there is a shortage of capital and entrepreneurship. Further, there was a lack of infrastructure facilities available for smooth functioning of businesses. An attempt has been made to improve infrastructure development by resorting to a ‘heavy borrowing’, as there is a savings-investment gap due to low household income.

However, one of the positive features of the economy is the rapid development of the welfare of the people measured in terms of life expectancy and the infant mortality rates including human development indices. One can argue that Sri Lanka has been able to achieve encouraging results in these areas mainly due to the continuation of the welfare activities, despite adopting a market economy during the last 40 years. The Human Development Index for Sri Lanka is 0 .78 which is on par with most of the developed countries.

Are there universal truths in economics?

Access to world markets in terms of capital, goods and services and technology has played an important role in the recent economic miracles by most of the countries. Proponents of neoliberals point out these examples when globalisation comes into question. When deployed appropriately, there is nothing wrong with markets and private entrepreneurship.

We should therefore, not throw out neoliberalism’s useful ideas. In order to arrest macroeconomic instability, the governments must pursue a sound monetary policy, which means restricting the growth of excess liquidity. They must also carry out regulation of banks and other financial institutions. They must ensure fiscal consolidation, so that the increase in public debt does not outpace national income. The tax base should be progressive and as broad as possible. The social security programs should be designed in a way that does not encourage workers to drop out of the labour market.

However, ‘alternate economists’ have argued that most of the developed countries joined the world economy by violating neoliberal strictures. Prof. Ha-Joon Chang is one of the eminent economists who advocates this view. He is a South Korean institutional economist, specialising in development economics at the University of Cambridge. Chang is the author of several widely-discussed policy books, most notably ‘Kicking Away the Ladder: Development Strategy in Historical Perspective’. Prospect magazine ranked Chang as one of the ‘Top 20 World Thinkers’ in 2013.

China turned to markets but did not copy Western practices in property rights and the country relied on mixed forms of ownership under Township and Village Enterprises (TVEs). These were collectively owned and controlled by local governments. Even though they were publicly owned, entrepreneurs received the protection against expropriation they needed. Local governments had a direct stake in the profits of the firms and hence did not want to kill the goose that lays the golden eggs.

Another two examples in China are; (i) the ‘dual-track’ pricing, which retained compulsory grain deliveries to the state but allowed farmers to sell excess produce in free markets, thus providing supply-side incentives, (ii) Special economic zones provided export incentives and attracted foreign investors without removing protection for state firms and hence safeguarding domestic employment. Few questions would be: Does trade liberalisation increase economic growth? Yes, if it increases the profitability of industries/firm where the bulk of investment and innovation takes place; but not otherwise. Does more government spending increase employment? Yes, if there is slack in the economy and wages do not rise; but not otherwise.

From the above it can be seen that calling China’s economic reforms a ‘neoliberal turn’ is not correct. South Korea and Taiwan heavily subsidised their exporters, the former through the financial system and the latter through tax incentives. All of them eventually removed most of their import restrictions, long after economic growth had taken off. Sweden is another classic example.

The eminent economist Keynes viewed international trade and investment as a means for achieving domestic economic goals—full employment and broad-based prosperity. The emphasis on economic growth is essential to all our social and political ends—prosperity, Entrepreneurship, private investment, democracy, and removing excessive regulation. This emphasis on economic growth, on the other hand, sacrifices other important values such as equality, social inclusion and justice. Those political and social objectives obviously matter.

Neoliberals are not wrong when they argue that their policies are more likely to be attained when the economy is vibrant, strong, and growing. Where they are wrong is in believing that there is a unique and universal recipe for improving economic performance. Economic principles must consider equity and social state policy.

The writer is of the view, that the economic sustainability can be achieved through undertaking programmes on social well-being and working towards environmental sustainability, in other words, by following the sustainability agenda. The writer is conversant with the practical application of ‘climate smart agriculture’ systems, both in paddy farming and tea growing and manufacture in order to mitigate climate change ill effects.

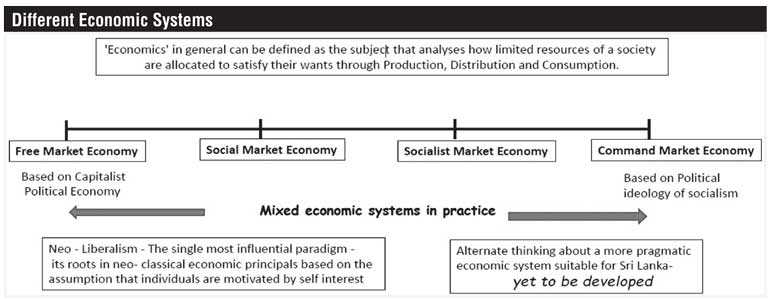

Coming back to alternative economic development models, the writer has identified different economic systems operating at present globally, and tries to present it in the following chart.

Politics must play a central role

Even the World Bank and the IMF have accepted that they have pushed liberalisation process too far and it had contributed to the global financial crisis. Joseph Stiglitz, former Chief Economist at the World Bank and winner of the Nobel Prize for Economics, in his book titled ‘Globalisation and its discontents’ mentioned: “Globalisation today is not working for many of the world’s poor…for much of the environment…” He argued that trickle-down economics was never much more than just a belief. It appears that even President Trump is of the same view in his America First concept.

Question whether neo-liberalism is a good thing or not can be answered by people differently. One could respond, yes, it’s good. Alternatively, he may ask. “What do you mean by ‘good?’” and “Good for whom?” Keynes once defined economics as the “science of thinking in terms of models joined to the art of choosing models which are relevant.” Ordinary people now question that the real problem is with the “art” part. One can therefore argue that the economic development cannot be achieved by means of technocratic economic policies; politics must play a central role.