Sunday Feb 22, 2026

Sunday Feb 22, 2026

Thursday, 26 October 2017 00:00 - - {{hitsCtrl.values.hits}}

Comparatively, only 79% of Grade 5 students in underprivileged provincial schools – which accommodate the poorest – take the exam. Ironically, those for whom the exam is most relevant, are the least likely to take it – Pic by Shehan Gunasekara

By Ashani Abayasekara

The 2017 Grade 5 scholarship exam results were released in early October, with 356,728 candidates sitting for the exam across Sri Lanka. As usual, details of the top scorers were highlighted in the media.

But, apart from a handful of successful students, how many manage to score above the cut-off mark each year? Does the exam serve its intended objectives? Is it worth the time, money, and effort spent by young children and their parents? This blog seeks to answer these questions, using data from the 2016 School Census conducted by the Ministry of Education (MOE).

The scholarship exam, introduced in 1948, aims to meet two main objectives: (1) admitting talented students to popular and more prestigious schools; and (2) providing bursaries to bright, but economically disadvantaged, students.

It measures ability and learning potential across 14 specified areas, and tests knowledge on the first language, mathematics, and environment. Regardless of its specific purposes, the exam is taken by students in both privileged and underprivileged schools, as well as across different socioeconomic groups. Children are coached from as early as Grade 2 to achieve high scores, not only in schools, but increasingly in many private tuition classes.

Despite the overzealous preparation, according to the Department of Examinations (DOE), only around 10% of students who sit for the exam obtain sufficient marks to qualify for bursaries and to apply for better schools, each year. This figure is not surprising, given that students need to score around 80% to meet the cut-off mark, while getting access to more popular schools requires scoring as much as 90%. This is no mean feat for a 10-year old, as it leaves very little margin for error.

What are the chances of getting into better schools?

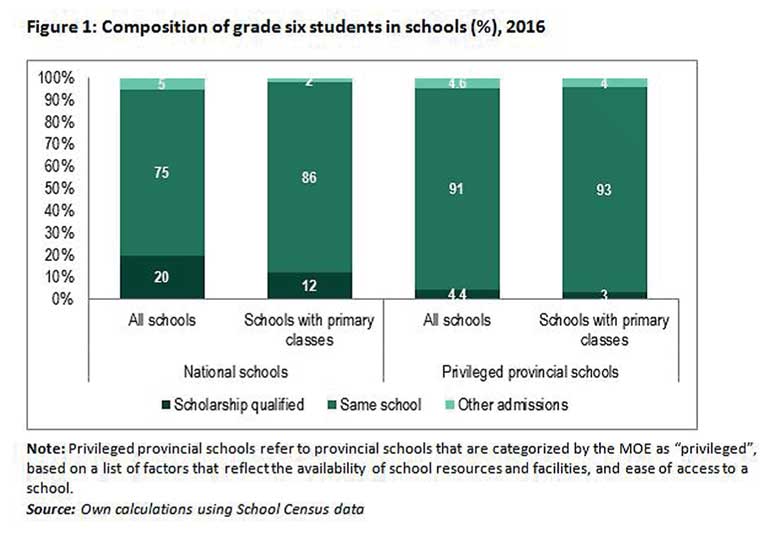

Figure 1 shows that the chances of getting into good schools based on the scholarship exam marks are slim. The share of Grade 6 students admitted to all national schools, based on scholarship exam results, is 20%.

When national schools without a primary section, i.e. schools offering only secondary classes (Grade 6 and above) are excluded, this share falls further to 12%. This is because many students who are in national schools at the primary level automatically continue to Grade 6, irrespective of performance at the scholarship exam.

This trend is seen in the large share of Grade 6 students – 75% in all national schools and 86% in national schools with primary classes – who are from the same school. As such, the chances to enter better schools via the scholarship exam are limited. The situation is similar in privileged provincial schools. Those entering through exam results are a mere 3-4%, compared to over 90% who automatically enter Grade 6 from the primary level.

What share of students gets financial aid?

Only around 36% of students who scored above the cut-off mark in 2015 were eligible to claim financial aid, according to School Census data. As a share of all Grade 5 students who sat for the exam, this amounts to a mere 3.6%. To receive these funds, a child needs to be from a household earning an annual income of less than Rs. 50,000, in addition to scoring above the cut-off mark.

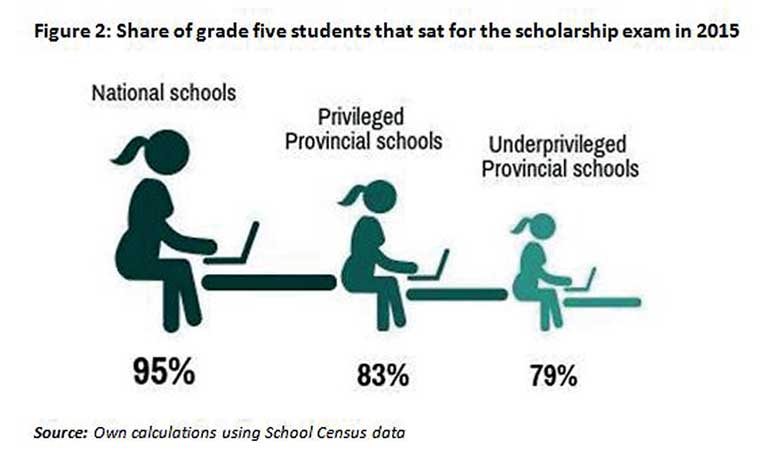

A reason for this low share is that a fair number of poor students do not even sit for the exam. As Figure 2 shows, national schools account for the largest share of scholarship exam candidates, at 95%. These are the best schools in the country, mostly attended by children from affluent families.

Comparatively, only 79% of Grade 5 students in underprivileged provincial schools – which accommodate the poorest – take the exam. Ironically, those for whom the exam is most relevant, are the least likely to take it. This could in part be due to lower access to educational resources, including private tuition.

Is financial aid adequate?

The monthly stipend for those who qualify for the bursary is a mere Rs. 500. This is negligible, compared to funds spent over the years on private tuition, which can cost between Rs. 600 to as much as Rs. 5,000 a month, depending on the quality and the popularity of tuition classes. Moreover, with inflation, the real value of the monthly stipend falls over time.

Moving forward

The above analysis suggests that the scholarship exam fails markedly in meeting its intended objectives. Given the pressure and the stress young children are put through in preparation for this exam, a serious reconsideration of its need and purpose is warranted.

An essential step in moving forward is developing better quality secondary schools, especially in rural areas. A defining feature of the Finnish education system, which is consistently ranked first in the world, is its equitable school system. Over and above aiming for top results, its key target is to provide good schools for all children. As a result, there are no required standardised tests, apart from one exam at the end of high school. Nor are there any rankings, comparisons, or competition between students or schools.

If the Sri Lankan Government’s proposed project to build 1,000 high quality secondary schools across Sri Lanka is carried out effectively, students will have more access to better quality schools without being forced to perform within the top 10% at the scholarship exam. Capitalising on this initiative, the classification of ‘national’ versus ‘provincial’ schools should also be removed, which will eventually eliminate the need for the exam altogether.

Another option is to enhance the quality of existing ‘feeder primary schools’ – primary-only schools which are linked and have guaranteed access to a given secondary school – as has been suggested in the proposed Education Sector Development Framework Programme: 2012–2016. Graduates from these schools can then transfer to an upgraded and nearby secondary school, without the burden of performing well at the scholarship exam.

While addressing the current unfair system where children who begin their education in good schools enjoy continued privileges at the secondary level, over time this should reduce the intense demand for distant schools, and the need for the exam. Any financial needs of students can be met by extending support to all poor children via income supplement schemes.

Building and upgrading schools is however a challenging and long-term task for Sri Lanka. In the meantime, the structure and content of the scholarship exam needs change. As mentioned in a recent IPS blog, Singapore’s education system is a good example for Sri Lanka to emulate, where assessments are increasingly based on a broad spectrum of areas, including sports, aesthetics, and life skills, in addition to test scores. While the competition to enter better schools would still be high, by allowing children to excel in what they like and do best, they can at least navigate school admission hurdles in less stressful ways.

(Ashani Abayasekara is a Research Officer at the Institute of Policy Studies of Sri Lanka (IPS). To talk to the author, email [email protected]. To view this article online and to share your comments, visit the IPS Blog ‘Talking Economics’ - http://www.ips.lk/talkingeconomics/)