Tuesday Mar 03, 2026

Tuesday Mar 03, 2026

Tuesday, 13 June 2023 00:10 - - {{hitsCtrl.values.hits}}

Labour law reform is an issue of national importance and must reflect the views of all stakeholders, particularly those directly affected, the workers

Labour law reform is an issue of national importance and must reflect the views of all stakeholders, particularly those directly affected, the workers

The Lawyers for Democracy (LfD) has made the following submission on labour reforms in Sri Lanka to the Secretary of the Labour and Foreign Employment Ministry. The submission was by Lal Wijenayake, on behalf of the Convenors of Lawyers for Democracy: Lal Wijenayake, K.S. Ratnavale, (Dr.) Jayampathy Wickramaratne PC, Ermiza Tegal, Attorneys-at-Law

Lawyers for Democracy notes that the Ministry of Labour and Foreign Employment has called for inputs to labour reforms in Sri Lanka.

The history of Sri Lanka’s labour law regime is linked to the goals of social protection, the concept of dignified labour and the prevention of extreme exploitative practices. Sri Lanka’s hard-fought and strong labour laws have been challenged since it liberalised its economy and traded in foreign investment capital, our strong labour laws and during the last four decades, there have been many attempts to loosen the grip of these legal protections. We note that proposals representing the interest of employers, even during the public consultations aired by the Ministry, represent not new recommendations but a repetition of previous recommendations that have time and again in the past been proposed to weaken labour protections and remove State oversight over labour relations.

Whilst there has been a need for labour reforms in Sri Lanka, we are concerned that this is not the context in which to consider legal reforms hastily. An unprecedented economic crisis ought not to be the context within which lasting legal reforms are undertaken. Extraordinary times cannot responsibly determine laws for ordinary times. In the event such reforms are contemplated, there is an immensely high burden to ensure that the crisis conditions do not skew and are not used or exploited to benefit the employer. The crisis has impacted both employers and employees. It has rendered workers vulnerable to loss of livelihood, and income insecurity, almost halving their purchasing capacity and leading to food insecurity and various health concerns for their families.

Consultations at this time are likely to focus on the more powerful voices of employers who would be, as expected, seeking to secure margins of profit and proposals from this quarter will have a strong likelihood of disadvantaging the employee, perhaps even creating conditions for exploitation. This must be recognised, and legal reforms must not pave the way for the regression of hard-fought rights of workers and unions.

We are extremely wary that the power dynamic that shifts further in favour of the employer, in a context where the employer’s interest often is simplistically framed in the language of national interest, if it influences the law-making process, will be unconstitutional. Article 27(7) of the Constitution requires the Sri Lankan State to ‘eliminate economic and social privilege and disparity and the exploitation of man by man or by the State’.

It is vital at this juncture to recall that the labour law regime and jurisprudence in Sri Lanka have been hard-fought achievements to secure the dignity and value of workers in the Sri Lankan economy and social development of the country. Labour laws reflect the standard of social and economic rights secured on behalf of the people of Sri Lanka. Any national discourse about the subject must, in conformity with Sri Lanka’s obligations under the International Covenant on Economic, Social and Cultural Rights, be non-regressive and progressively enhance the social rights achieved.

Labour law reform is an issue of national importance and must reflect the views of all stakeholders, particularly those directly affected, the workers. The bedrock of labour law gives due recognition to the asymmetry of power in the relationship between employee and employer and the role of the State in ensuring that the worker is protected from exploitation. Dignified productive labour ought to be a hallmark of the country’s economic policy. Given the economic crisis in Sri Lanka and the national pressures on all industries and the agricultural sector, labour reform discussions are susceptible to undermining basic safeguards for which workers and unions have struggled.

a) Refrain from the hasty formulation of labour law reforms given the context and also the extremely vulnerable condition of the worker in the given context. Do not make ordinary law in extraordinary conditions.

b) Ensure that consultations with workers and trade unions are transparently and genuinely conducted, including at the level of the National Advisory on Labour Council. This would be time to ensure full and wider consultations feeding into the Council, given the extraordinary nature of the labour context in this crisis.

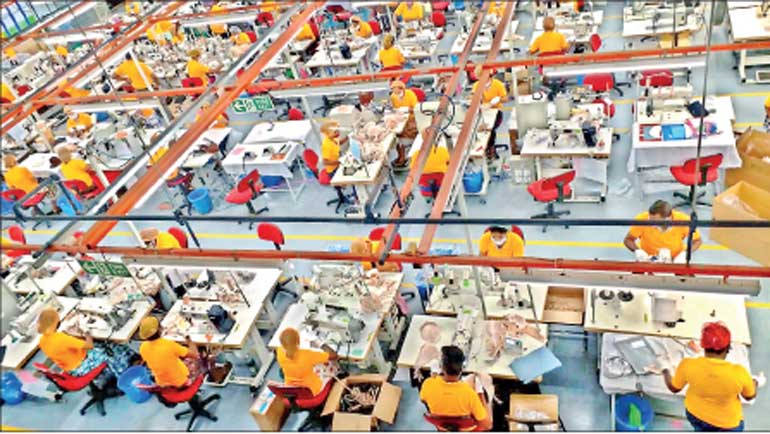

c) Recognise the historical discrimination, vulnerability and exploitation caused to sections of workers such as free trade zone workers, plantation workers and informal sector workers and the ongoing attempts of informatisation and trade union busting in the various sectors and ensure that measures taken do not aggravate these ill practices.