Sunday Feb 15, 2026

Sunday Feb 15, 2026

Thursday, 30 September 2021 00:00 - - {{hitsCtrl.values.hits}}

It is not surprising that the informal sector has been the most hard-hit during the pandemic

By Alessia Destefanis, Tetsushi Sonobe, Dil Rahut and Jeetendra Prakash Aryal

The informal sector: A major source of livelihood

The informal sector, which employs over 62% of the global population, is a fundamental source of livelihood for over two billion people (ILO 2020). Here, ‘employment’ includes self-employment, and the informal sector refers to the part of the economy that is generally not monitored by a tax authority or other forms of government.

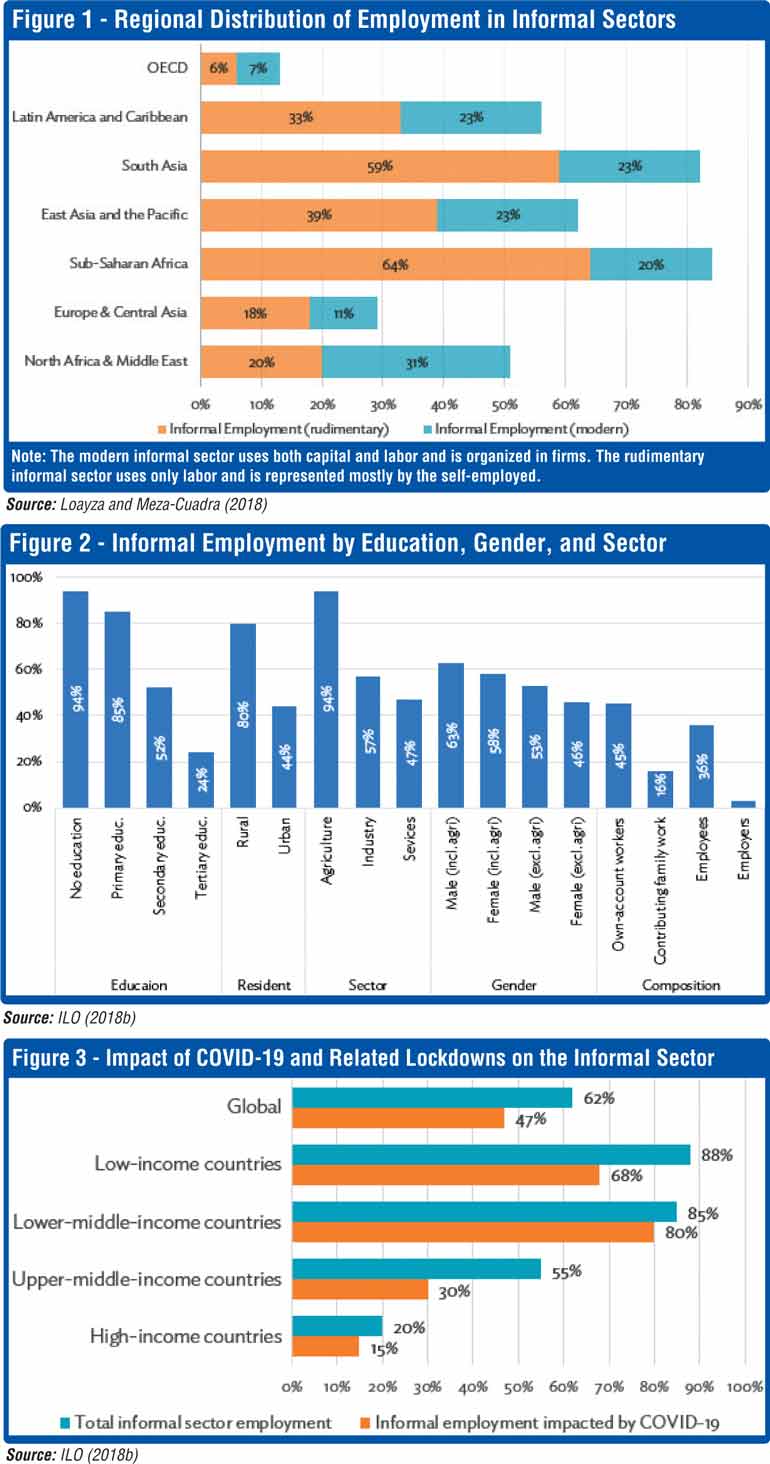

Before the outbreak of the coronavirus disease (COVID-19), the informal sector accounted for 87.7%, 51.5%, and 55.7% of the population in low-, middle-, and high-income countries, respectively (ILO 2018a). The proportion was particularly high in low-income countries (ILO 2018b). A wide variation in the share of the total population employed in this sector was observed across regions in 2018 (Figure 1), with shares of 84% in sub-Saharan Africa and 82% in South Asia but 29% in Europe and Central Asia and 13% in the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD) countries.

Temporary construction workers, daily agricultural laborers, domestic cleaners, small vendors, and tourist guides were among the most common informal employment activities. Figure 2 highlights that as the level of education increases, the percentage of the population employed in the informal sector declines dramatically. Informal sector employment is concentrated in rural areas: about 90% are in the informal sector in the agriculture sector, compared with only 57% in the industrial sector and 47% in the service sector. The percentage of females in the informal sector is lower than for males (63% male and 58% female), and the composition shows that 45% are self-employed or own-account workers, 36% are employees, and only 3% are employers.

Both self-employment and wage-employment in informal sectors generally do not require registration, and the skills and investment needed are minimal. Consequently, it is relatively easier to get entry into and exit from this sector, primarily for those who possess very low levels of education, training, and other economic resources. Nevertheless, employees in the informal sector in developing countries have been outside the purview of labour laws, insurance, pension, retirement benefits, and social protection schemes (Narula 2020).

Furthermore, wages and returns have generally been low and experienced large variability (Binelli 2016; Meghir, Narita, and Robin 2015). Combined with a lack of endowments and savings, individuals in the informal sector have been socially vulnerable and facing the constant challenges of exploitation, health shocks, and retirement issues (Gidwani 2015). Not all individuals in the informal sector are poor and vulnerable; it is important to acknowledge the existence of socioeconomic heterogeneity.

The informal sector has suffered the most from the COVID-19 pandemic

It is not surprising that the informal sector has been the most hard-hit during the pandemic. The outbreak of COVID-19 has led to the collapse of meagre health systems and increased poverty through widespread job and earnings losses.

Figure 3 shows that the lockdowns and declines in economic activities have severely affected 47% of the two billion people dependent on the informal sector. It shows further how the pandemic has impacted most of the individuals belonging to the informal sector in low-income and lower-middle-income countries. As a result of this pandemic, poverty will increase, making it difficult to achieve the Sustainable Development Goals by 2030: in 2020, 131 million additional individuals fell below the poverty line, and 797 million will remain in poverty in 2030 (United Nations 2021).

Nonetheless, global poverty could be even worse in the future as COVID-19 continues to ravage the world, and intervention is taking more time than anticipated. Globally, casual or temporary wage workers and even regular workers have lost their jobs regardless of industry, location, education, or social position. Among them, those individuals working in tourism, hotels, restaurants, and construction, as well as those employed as food vendors, have been the most hard-hit by lockdowns (Ferreira dos Santos et al. 2020).

In addition, the COVID-19 job losses may increase gender inequality as women are less likely than men to recover to their pre-COVID-19 levels of livelihood and employment (Agarwal 2021; Dang and Viet Nguyen 2021). In the developing world, thus, the lives and livelihoods of informal-sector households, especially those headed by females, are being endangered by the pandemic.

Way forward

Globally, the immediate response to COVID-19 was to keep social distance and to contain the virus with lockdown measures. In the informal sector, this individualistic approach has either paralysed economic activities, endangered livelihoods, or failed to protect individuals, endangering lives and, hence, calling for the next response in casting a social safety net. Although some developing countries have social safety net programs, their implementation has in many cases been crippled by inefficient public delivery systems that are plagued by a lack of transparency (Chakrabarti, Kishore, and Roy 2016). This is far from surprising: it is very difficult for the government to reach out to vulnerable groups because most of them are in the informal sector, about which, by definition, the government has little knowledge.

Nonetheless, some notable successes have emerged recently. For instance, Pakistan’s Ehsaas (meaning ‘compassion’ in Pakistani) is a very large social protection program that was created a year before the outbreak of COVID-19 and has proved to be excellent during the pandemic. The Mahatma Gandhi National Rural Employment Guarantee Scheme has also emerged as a successful program and aims to enhance the livelihood security of people in rural India by guaranteeing 100 days of wage employment in a financial year to rural households whose adult members volunteer to do unskilled manual work.

Digitalisation, transparency and accountability, integrity policy, impartiality, political neutrality, avoidance of fragmentation, regular monitoring, and evaluation are key ingredients of the success of social safety net programs.

National resilience capacities are not equally developed around the globe. Hence, absent of any social insurance coverage, many informal workers in low-income areas have entered the so-called poverty trap. Further, limited resources and competing priorities make the situation challenging for low-income countries. To integrate the informal sector into the mainstream economy, the Government of India launched the National Pension Scheme for Traders and Self-Employed Persons on 22 July 2019 (Vikaspedia 2021).

It is, therefore, clear that achieving a sustained and equitable recovery is necessary to limit further inequalities. In light of the fundamental role played by the informal sector for both local livelihoods and economies, it is imperative to design and invest in transparent, efficient, and well-targeted public safety nets and insurance systems. Public distribution networks should be made more resilient to shocks, and food supply chains need to be more responsive to match varying demand (Singh et al. 2021).

Attention should also be paid to building individual-funded public/private retirement or pension funds. Governments should value informal livelihoods by protecting them and including them in economic development plans at both the national and local levels. Combined together, these initiatives can contribute to coping better with both idiosyncratic and covariate risks while simultaneously integrating the population engaged in the informal sector into the economic life of a country.

The advent of digital technology has helped in improving registration processes, transparency, monitoring, and evaluation, thereby improving the efficiency of the social safety net program. Therefore, using digital technology together with financial inclusion policies ranging from inclusive insurance and pension schemes to financial literacy improvement has made it possible to develop and implement the registration process, cash transfer, and provision of other public services quickly and without corruption.

(Source: https://www.asiapathways-adbi.org/)

References:

Agarwal, B. 2021. Livelihoods in COVID Times: Gendered Perils and New Pathways in India. World Development 139: 105312.

Binelli, C. 2016. Wage Inequality and Informality: Evidence from Mexico. IZA Journal of Labor & Development 5: 5.

Chakrabarti, S., A. Kishore, and D. Roy. 2016. Arbitrage and Corruption in Food Subsidy Programs: Evidence from India’s Public Distribution System.

Dang, H.-A. H., and C. Viet Nguyen. 2021. Gender Inequality during the COVID-19 Pandemic: Income, Expenditure, Savings, and Job Loss. World Development 140: 105296.

Ferreira dos Santos, G., L. C. de Santana Ribeiro, and R. Barbosa de Cerqueira. 2020. The Informal Sector and Covid-19 Economic Impacts: The Case of Bahia, Brazil. Regional Science Policy & Practice 12: 1273–1285.

Gidwani, V. 2015. The Work of Waste: Inside India’s Infra‐Economy. Transactions of the Institute of British Geographers 40: 575–595.

International Labour Organization (ILO). 2018a. Informality and Non-Standard Forms of Employment. Prepared for the G20 Employment Working Group Meeting Buenos Aires. Geneva, Switzerland.

ILO. 2018b. Women and Men in the Informal Economy: A Statistical Picture. Third Edition. Geneva, Switzerland: ILO.

ILO. 2020. COVID-19 Crisis and the Informal Economy: Immediate Responses and Policy Challenges. Geneva, Switzerland: ILO.

Loayza, N., and C. Meza-Cuadra. 2018. A Toolkit for Informality Scenario Analysis. Washington, DC: World Bank.

Meghir, C., R. Narita, and J.-M. Robin. 2015. Wages and Informality in Developing Countries. American Economic Review 105: 1509–1546.

Narula, R. 2020. Policy Opportunities and Challenges from the COVID-19 Pandemic for Economies with Large Informal Sectors. Journal of International Business Policy 3: 302–310.

Singh, S., R. Kumar, R. Panchal, et al. 2021. Impact of COVID-19 on Logistics Systems and Disruptions in Food Supply Chain. International Journal of Production Research 59: 1993–2008.

United Nations. 2021. World Economic Situation and Prospects 2021. New York: United Nations, Department of Economic and Social Affairs.

Vikaspedia. 2021. National Pension Scheme for Traders and Self Employed Persons Yojana (Pradhan Mantri Laghu Vyapari Maan-dhan Yojana).

(Alessia Destefanis is a student at the Paris School of Economics. Tetsushi Sonobe is Dean and CEO of the Asian Development Bank Institute. Dil Rahut is a senior research fellow at ADBI. Jeetendra Prakash Aryal is a consultant for various organisations, including the International Maize and Wheat Improvement Center (CIMMYT) and ADBI.)