Friday Feb 20, 2026

Friday Feb 20, 2026

Saturday, 17 October 2020 00:04 - - {{hitsCtrl.values.hits}}

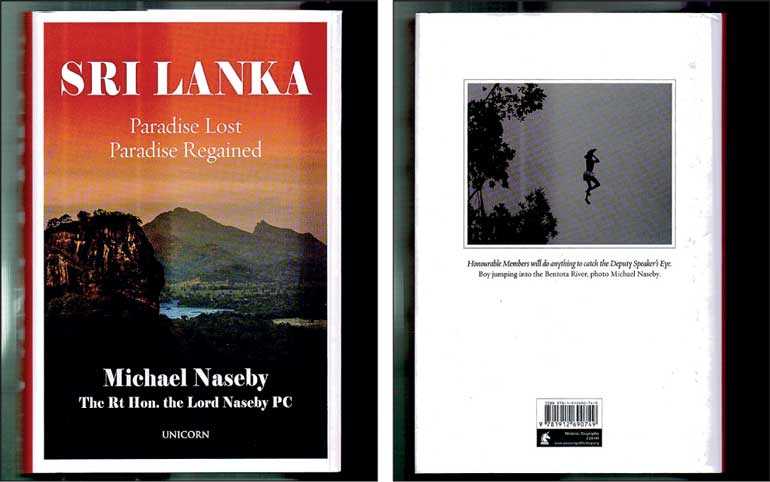

‘Sri Lanka: Paradise Lost; Paradise Regained’ is a must-read for all those who are concerned about the recent past and the promising but unclear future of the island of Sri Lanka

By Dr. Sarath Chandrasekara

|

Lord Naseby

|

I had the privilege of reading the book titled ‘Sri Lanka: Paradise Lost; Paradise Regained’ by Michael Naseby. Of all those Western/European travellers and writers who fell in love with the island of Taprobane or Sielediba or Serendib or Ceyloa or Zeylan or Ceylon or Sinhaladipa and wrote about it, three stand out for me.

The first one is Robert Knox. Knox, being an English sailor, was captured in 1659 by King Rajasinghe II of the Kandyan kingdom. Knox enjoyed a considerable degree of freedom over twenty years before he made his escape. In his monograph he adored the Sinhala culture, certain Sinhala customs, folk lore, and the beauty of Ceylon.

Knox “earned his living by various means such as peddling, knitting, farming, and lending rice and corn at 50% interest to the villagers (Sebastian: 2013; p 497). Knox first lived in Lagumdeniya village, near Gampola and later moved to Undunuwara and constructed a house there. Knox’s work has been commended by many British writers who considered that Knox’s description of the Isle of Ceylon was written with great truth and integrity.

The second person I admire is Major Roland Raven-Hart who sailed from South Africa and spent 15 years in Ceylon from 1963. Raven-Hart could read and write 13 languages and speak five. In his story entitled Ceylon: History in Stone (1964) he expresses his gratitude to the “people of Ceylon, from monks to schoolboys and from Rest House keepers to servant-boys. Thanks to them I enjoyed my 15 years in Ceylon.”

The third person about whose book that I am writing this review is Michael Naseby, popularly known as the Right Honourable the Lord Naseby PC. Of all three writers I read carefully, Lord Naseby appears to be the most passionate writer about Sri Lanka and its people.

He first visited Ceylon (Sri Lanka) in 1963 and since then, he has been to Sri Lanka about 20 times, some short visits and others longer sojourns.

‘Sri Lanka: Paradise Lost; Paradise Regained’ is comprised of 19 chapters covering 333 pages. It also provides appendices of 54 pages containing his letters and memos written to various political authorities in UK, UN, and other relevant agencies. Lord Naseby had a remarkable career in the British Parliament from 1974 and, although he did not become a minister, he was Deputy Speaker from 1992 until 1997 when he became a member of the House of Lords.

Lord Naseby’s personal memoir is written as a narrative that any English reader can understand easily. I have found a historian, a storyteller, a narrator, an analyst, and an ardent lover of Sri Lanka in his paragraphs. In summary, the book is a political and social analysis of the recent history of Sri Lanka which underwent a disastrous turbulence due to the internecine armed conflict during 1983-2009.

His paragraphs are full of evidence-based facts and figures. His arguments are thought provoking and insightful. His narrations are embedded with ever growing love and affection for the people and the island of Sri Lanka.

The colourful variety of his direct involvements with Sri Lanka are reflected in his roles as the marketing manager of Recitt & Colmen, as the Leader of an all-party group of British MPs, as the go-betweener (or matchmaker) between the Government of Sri Lanka and the British parliamentarians and civil servants, and as a close friend of the country, highly trusted by the Presidents, Prime Ministers and other political leaders of the Sri Lankan State.

At this juncture, I need to dwell on some hard facts and information Lord Naseby is discussing in his personal memoir.

Charges levelled against administration and Army

In all his chapters Lord Naseby is trying his best to alleviate myths and refute charges levelled against the political and public administration and the Army of Sri Lanka. He firmly believes that agencies like UNHCR, Amnesty International, Human Rights watch, and several other Western media agents have portrayed a grossly inaccurate picture of the island, its Army and its leadership. The above agencies and even British politicos like Prime Minister Tony Blair, Foreign Secretary David Miliband, Prime Minister Cameron, and Hilary Clinton of the USA have been misled with false information provided by the Tamil diaspora groups in those countries.

Lord Naseby based his arguments primarily on his personal observations, despatches sent by Colonel Gash, the Defence attaché of the British High Commission in Colombo, and International Red Cross officers based in the Northern and Eastern provinces of Sri Lanka.

He clearly spells out reasons as to why several peace talks between the Tamil Tigers and the government of Sri Lanka failed. He has repeatedly pointed out that the on-going ethnic issues in Sri Lanka between the majority Sinhalese and the minorities could be resolved without resorting to violence which the Tamil Tigers used as their main instrument.

Some unnecessary influences of India and the US and inactive support rendered with restraining orders by European Union and the UN have extended the armed conflict for such a long duration of about 30 years. Such a prolonged internecine war within a small island like Sri Lanka resulted in an irreparable destruction of its economy, social structure, and day-to-day human relations.

It is not difficult to surmise that incessant failures to come to a long-lasting peace agreement mainly due to LTTE reluctance and over confidence of the LTTE leaders in winning the war, would have driven the Sri Lankan army to resort to a military ending of the armed conflict.

As an independent critic of the war situation in Sri Lanka, I began to wonder whether the Western power holders benefitted from the instability of the country which they in their public face admired as the pearl of the Indian Ocean.

Naseby in his analysis refers to specific incidents like the cold-blooded massacre of 600 policemen (June 11th, 1990) who surrendered to the LTTE in the Eastern Province of Sri Lanka. He treats this as “one of the greatest war crimes in the whole of the conflict between the Government of Sri Lanka and the Tamil Tigers” (P. 89). Tamil Tigers forcing 72,000 Muslims in Jaffna to leave within 24 hours and killing 300 Muslims who were attending a prayer session are considered ‘ethnic cleansing” by the truest sense of the word.

Lord Naseby had never met the LTTE Leader Prabhakaran but has done some homework regarding Anton Balasingham’s strategic thinking. Balasingham’s approach was probably flawed from the beginning. Norwegian efforts have not brought desired results in resolving the conflict. According to Naseby, the UN was more interested in prosecuting for alleged war crimes after the event rather than concentrating on preventing such disastrous events. The British Government has apparently turned a blind eye being frightened by the Tamil diaspora votes in the UK.

Lord Naseby regarding the deaths of people during the last days of the war asserts that: “At most as the Sri Lanka census undertaken by Tamil officials says between 6,000 and 7,000 but that also includes the deaths of Tamil Tigers…. What is clear is that it was never, ever, anywhere near tens of thousands or the minimum of 40,000, as claimed by the UN in the Darusman Report. It is also clear that the UK Government knew by 19 May 2009 – the end of the war – that 40,000 was a hopeless exaggeration but never said so. I wonder why.” (pp189-190)

Lord Naseby further asserts that the report published in March 2015 with the title of ‘Office Investigation on Sri Lanka’ by the OHCHR (Office of the High Commissioner for Human Rights) contained many inaccuracies connected with shelling in the war, short supply of food, etc. (p. 189). As Lord Naseby indicates “this report ignores the self-evident fact that this was a war between the democratically elected and legitimate Government of Sri Lanka and a terrorist group, the LTTE Tamil Tigers”. To combat and battlefield situations, the European Convention on Human Rights is wholly inappropriate.

Encounters and dealings with Sri Lankan politicians

The author’s encounters and dealings with Sri Lankan politicians like J.R. Jayewardene, Ranasinghe Premadasa, Gamini Dissanayake, Lalith Athulathmudali, Chandrika Bandaranaike, Maithripala Sirisena, Mahinda Rajapaksa and Gotabaya Rajapaksa are vividly described in the book.

Their varied individual thoughts about the ethnic issue are measured while showing his admiration of their personalities. He even blames J.R. Jayewardene for not taking timely action to control the 1983 riots carefully planned and executed by a group of thugs with political affiliations.

Among Lord Naseby’s friends there were Kandyan families, non-political Sri Lankans, reputed Tamils and even gem merchants, jewellers, and goldsmiths. His wife Dr. Ann was his companion in many of his visits.

Colonel Gash’s war time reports

The last four chapters (16-17-18 and 19) contain his discussion and analysis of difficulties in getting Colonel Gash’s war time reports published. The author strongly felt that without releasing Colonel Gash’s reports to the UN enquiry by the British Government, Sri Lanka would be placed in an exceedingly difficult situation to fight against charges.

Chapter 17 is about charges levelled against the Sri Lankan Government. The author attempts to refute charges one by one with facts and figures. The charge of a “genocide” claimed by the Tamil diaspora communities is systematically refuted using an array of evidence from different sources including that of Dr. Shanmugarajah who worked closer to the LTTE operations centre.

According to Lord Naseby, the reports of Colonel Gash made it clear that the Army behaved admirably and looked after the civilians. The 295,000 civilians would not have been brought across the lines safely if the army wanted to knock them down.

In his last paragraph of the 18th chapter the author is asking a pertinent question: “Would it not be far better for the West to recognise the pool of talent the young people of Sri Lanka offer? What better epitaph to all the young people, be they child soldiers or young Government soldiers, sailors or airmen, indeed young and not so young troops on all sides who gave their lives and were killed in the line of duty, to defend the unitary state of Sri Lanka?” (p.245).

When Lord Naseby discusses Sri Lankan politics, he always brought similar examples from British politics. Lord Naseby has always found time to visit different places of the island of Sri Lanka.

A must-read

He concludes his thought-provoking memoir with the following words: “Sri Lanka… this wonderful country – which it really is – and its creative people will truly have regained ‘paradise’. Anyone who has any real thought for the future good of this tremendous country should leave it ALONE. Let the citizens of Sri Lanka choose themselves how to rebuild this paradise island.”

‘Sri Lanka: Paradise Lost; Paradise Regained’ is a must-read for all those who are concerned about the recent past and the promising but unclear future of the island of Sri Lanka. All UN agencies, foreign ministers and foreign secretaries of powerful nations and media personnel of global networks must read this book before they re-frame allegations against Sri Lanka and its people.

The book reveals a lot about Lord Naseby, the man, particularly his persistence in chasing after accuracy. His loving kindness and compassion won him several valuable friends in Sri Lanka with whom he could discuss politics frankly.

All Sri Lankans should be proud that someone like Lord Naseby, a British parliamentarian, has been there to speak out for them at a time when all big powers in the West were playing games against Sri Lanka on the stage of world politics.

(The writer is an ex-Canadian Federal Civil Servant. He teaches sociology at two Canadian universities now.)

References: