Sunday Feb 22, 2026

Sunday Feb 22, 2026

Monday, 25 November 2019 00:00 - - {{hitsCtrl.values.hits}}

MTI’s thought leadership team comprising Hilmy Cader (CEO), Rajika Sangakkara (Sri Lanka), Jason Cordier (New Zealand), Darshana Buragohain (India) and Darshan Singh (UK/Bahrain)

The decision to limit the Cabinet to 15 (sans the entourage of deputies and State ministers), be it motivated by legislation or the new leadership, is certainly a step in the right direction. Hope it stays this way – in terms of the cadre of ministers.

The focus of this piece is on how to allocate the ministerial portfolios. In the current allocation, there seems to be some effort to group related subjects together, although not significantly different to what it was earlier. In both cases, what has been done is to take the existing portfolios (in its legacy definitions) and allocated among the ministers.

Therefore, it still remains an unwieldy allocation of portfolios – which lacks focus on clear end deliverables that benefits the population (which should be the ultimate intent of a minister’s job).

Therefore, MTI Consulting (with extensive international and local re-structuring experience across 40 plus countries) has applied proven re-structuring principals and models to arrive at an optimal cabinet portfolio allocation.

Admittedly, MTI’s experience is in organisational re-structuring and not cabinet re-structuring, but feel confident that strong principals and models are equally applicable (with intelligent customisation) to re-structuring the cabinet.

In any case, given the legacy practices in which cabinet portfolios have been allocated in the last 70 years, it can certainly benefit from a fresh, outside-in approach, which is what MTI Consulting is recommending in this piece.

Structuring considerations

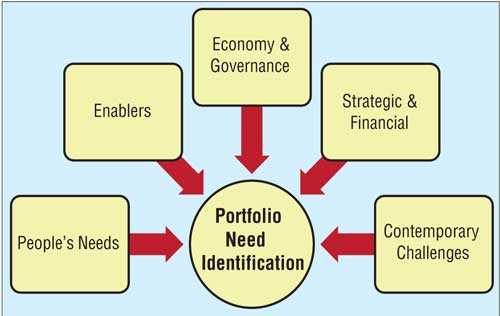

How was this ministerial portfolio structuring arrived at?

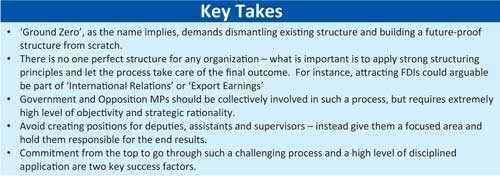

Structuring any organisation, irrespective of size and type, needs to be aligned to the purpose, direction and strategy of the organisation. This needs a very scientific approach, using purpose-specific structuring frameworks and an inclusive process of facilitating stakeholder involvement. If this process is entirely left to politicians, then it tends to be driven by political motives and not by what is in the best interest of the people of a country. The effectiveness of a government is significantly determined by the way it is structured, starting with the scoping and segmentation of the ministries – because all other government institutions are structured based on this ‘super structure’.

Governments tend to carry on with historical structures, with incremental portfolios added as and when the need arises e.g. technology, disaster management, national integration, etc. or combining unrelated portfolios (see inset).

There has also been a tendency to create a plethora of micro focused responsibilities e.g. wild life, botanical gardens, private transportation. The net result of all these is a cluttered portfolio of ministries that lack focus. The installation of a new government is an ideal opportunity to go completely ground-zero and develop the ministerial portfolios based on the strategic needs of the country. Such a process could then lead to rationalising and re-structuring/re-scoping the large number of state institutions that operate within the ministries

Step 1: Go completely ‘Ground Zero’

This means assume none of the current ministerial portfolios exist and avoid any reference to any current ministerial names, even later on in the process.

Step 2: Apply ‘people’s need’ as the first basis of structuring

Governments exist only to serve/meet the needs of people. Therefore, in structuring the government, it should be based on the specific needs of the people. Start with basic human needs, hierarchically exploring all types of physical, physiological, social, safety and economic needs. If the above is applied to the Government of Sri Lanka, the first-cut based on people’s need will be as seen in the table.

Step 3: Identifying the ‘economy and governance’ based ministerial needs

Beyond the people’s needs, at a macro level the government needs to manage the economy and ensure effective governance (including the effective management of all other ministries) – this then leads to the need for other ministries.

In order to ensure and manage all portfolios identified (applying multiple criteria), what types of economic management and governance functions needs to be undertaken? Accordingly the following has been identified as the ‘first-cut’ list.

Step 4: Strategic and financial implication for ministerial portfolio

In identifying the ministries based on the ‘people’s needs’ and ‘economy and governance’, there is tendency for wide variation in the scope and scale of the ministries identified and therefore some key functions may not get adequate focus. Estimating the strategic and financial value of the portfolios (identified under each of the other modules) and then deciding which ones require further segmentation.

Step 5: Contemporary national challenges that demand ministerial focus

The world we live in today confronts us with dynamic socio-economic and political challenges, which governments need to respond and in some cases there needs to be institutions to manage/respond to these challenges.

Evaluate all the current/emerging socio-economic and political challenges that the country encounters and decide if any of these warrant a dedicated portfolio. Accordingly, for Sri Lanka the following have been identified:

National integration

Disaster management

Step 6: Ministries that are needed for the ‘enabling’ role

When identifying the ministries based on the criteria under Steps 2 to 5, the focus is on the front-end needs, consequently the enabling ministries (also known as back office or shared services functions) do not get captured. For each of the ministries identified thus far, examine the need for the enabler role, based on which the enabling ministries have been identified.

Step 7: Rationalise the 36 ministerial needs that were identified by applying the five structuring criteria

Applying the five different criteria, we have arrived at 36 portfolios of varying scopes. While this is exhaustive, there is the possibility of over-laps and more importantly the need to rationalise and merge some of the portfolios – in the pursuit of ensuring a max of 15 cluster ministries (considered an optimal number).

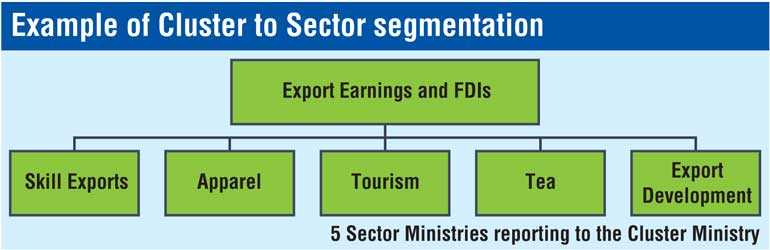

Step 8: Arriving at the final list of 16 ‘cluster ministries’

Arrive at the final list of 16 ‘cluster ministries’ by applying the following structuring principles:

This is only one example of the Ground-Zero model application – the end result depends on the quality of thinking and intellect that goes into the process. There could be several outcome possibilities and that’s not an issue, as long as there is process integrity and rigour.

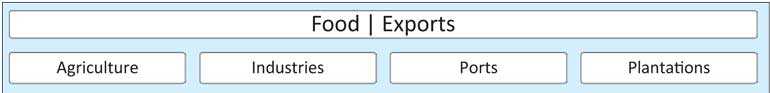

Step 9: Each of the ‘cluster ministries’ are then further segmented into ‘sector ministries’

Segment each of the ‘cluster ministries’ into ‘sector ministries’ using the same structuring principles as above.

Step 10: Set KRAs and KPIs

Each minister’s performance appraisal to be presented to both the Parliament and the public. Then, apply the process down to the next level of Government departments and SOEs.

MTI Consulting

MTI Consulting, Sri Lanka’s leading strategy consultancy, has worked on over 660 assignments in over 43 countries, covering a diverse range of clients, brands, industries and challenges.

MTI is powered by a pool of internationally experienced strategy consultants and analysts, augmented by a panel of specialists – by industry, function and geo-domains and like-minded boutique consultancy relationships in over 30 countries.

MTI has been at the cutting-edge of thought leadership on strategy, having presented at over 150 conferences around the world.