Tuesday Feb 17, 2026

Tuesday Feb 17, 2026

Tuesday, 19 December 2017 00:07 - - {{hitsCtrl.values.hits}}

By Sajeeva Samaranayake

Living within the world of print – also referred to as the Gutenberg Galaxy – we take for granted a number of changes that took place in communication to get here.

Noam Chomsky thinks that language is the method by which we human beings try to understand and express our thoughts. We began with the emotions of our tribal and herd mentality. These became thoughts or conclusions we tried to express with speech. Speech was systematised by language which sought to confine all the sounds we made within the four corners of an alphabet.

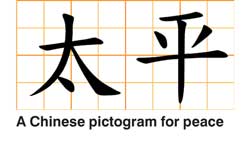

The alphabets provided a recognisable pattern to language. There are many alphabets. English is based on the Roman script and has 26 letters. Combinations of letters make up words. The Chinese alphabet assigns a picture to each word and it has many such “pictograms” in its alphabet – the dictionary containing no less than 40, 000!! You will need a knowledge of about 2,000 words to read the Chinese language.

The oral world

Some of our greatest teachers did not write. Socrates, Buddha, Jesus Christ were all great oral communicators. This oral tradition continued for several centuries after them and we need to learn more about this. How to talk well.

Once I realised the value of listening when Krishnamurthi advised his audience not to take notes but just listen. The modern human being has many distractions and many subjects and disciplines inside his or her head which makes the simple task of emptying the mind and focusing quite a challenge. This would not have been the mental condition of people who listened to the great ancient teachers. They were troubled and they had questions. However, the face to face meeting and the personal chat probably made the overall experience very rich.

With no written word to carry the meaning as an authoritative, impersonal middleman the instructions would hit you then and there. Your own body and mind became the site for putting the teachings into practice.

There were also tribal rituals and sacrifices around the fire. These were great meeting places which affirmed togetherness and sameness and solidarity. Stories narrated around the fire taught lessons about life and helped develop empathy and understanding. The environment was participatory.

Early Greek democracy was also an example of this participatory orality. They had one idea called “isegoria” which meant that everyone had to be listened to without any distinctions of high or low and regardless of how articulate or not they were. In fact, if a speaker was too fluent they became more suspicious about him.

Learning was a complete experience imbibed through all the senses. This meant that the senses were engaged and balanced. When all the senses are active in this way balance and moderation come naturally. There is a sense of a beginning, a middle and an end – something we can call an organic sense. The ideas of ehipassikoor “walk with me and come and see” and opanayikoor, gradual and gentle step by step learning, fit well into such an educational model.

Shift to writing

The shift from such a society to one that developed writings and gave pride of place to books could not have taken place without a number of precipitating factors. Here in Sri Lanka we know about the great famine during the reign of King Walagamba which prompted the Buddhist monks to take a momentous decision to codify the Buddha’s teachings.

Writing privileged the visual and cognitive organs of the human being over the other organs and it came between the ancient guru-disciple relationship, which was a cornerstone of eastern learning. A culture of empathetic engagement gave way to one of detached reflection.

The decision to codify (being a revolutionary one) was debated quite seriously by two groups of monks named as the dhamma preachers and the rag robe wearers (meditators). They posed an interesting question as to what is the basis of the Buddha’s dispensation (the Sasana) – “learning or practice.”

The former contended that if the learning or text is lost everything would be lost. The latter pointed out quite correctly according to the Buddha’s own advice that practice is more important than a lot of knowledge not tested in real life. The meditators lost and the Sasana became a religion of the book. This was the beginning of a process by which scholars would become pre-eminent in Sri Lanka while there would be no meditation masters worthy of international repute in both the pre-modern (post 13th century) and modern periods.

This election in favour of abstract knowledge was followed by the division of life into ‘subjects.’ These subjects would be mastered by pandits within the sangha. This anticipated the European age of reason and the egoistic cartesian educational model which would be established in conquered colonies.

Language to print

The final nail in the coffin of organic sense and holistic education would be the introduction of print to the colony. Sensory over-kill would become the norm as the natives were bowled over by modern technology. The printed word would convey and powerfully reinforce imperial values of centralisation and uniformity. Indoctrination as opposed to education would become the norm as both empathy and participation would be killed in favour of the mass production of qualified machines ready to take their place with other machines in modern workplaces. The loss of freedom would be celebrated as ‘progress’ and ‘development’.

In the words of Marshall MacLuhan – ‘the medium is the message.’ The message cannot be separated from the way we express it. There is no pure content. When we use a machine for  communication we may gain in efficiency but lose in terms of sensory balance and human meaning. This is how we have become strangers to each other today.

communication we may gain in efficiency but lose in terms of sensory balance and human meaning. This is how we have become strangers to each other today.

This essay was not written to glorify orality and denounce print. They are both modes of communication which we need to use with awareness of their relative advantages and disadvantages. However, each has features that conduce towards sensory balance and sensory imbalance. This should be kept in mind.

We can think of orality in terms of quality and print in terms of quantity. But these are just appearances. Beyond the appearance lies the quality and spirit of the communication and its power to connect human beings; what we call connectivity. If there is true connectivity and commonality we can then decide how much orality and how much print may be required to supplement our message. But initially the quality and substance must be there. It must be true. True to our deep self.

In this way the solutions to our human problems are defined by the quality of our human discussion and communication. Simply dressing something up as a law or policy or advertisement will be a waste of time. Our civilisation is threatened by junk which is disguised as ‘communication’. My idea of junk is quantity without connectivity and without meaning. We must leave something better for our children.