Tuesday Feb 17, 2026

Tuesday Feb 17, 2026

Tuesday, 8 December 2020 02:22 - - {{hitsCtrl.values.hits}}

“Wrongdoers are imprisoned to turn them into good people. Nothing like that happens inside this prison. People who are imprisoned for committing one wrongful act, go out learning 10 other wrongful acts – Prisoner

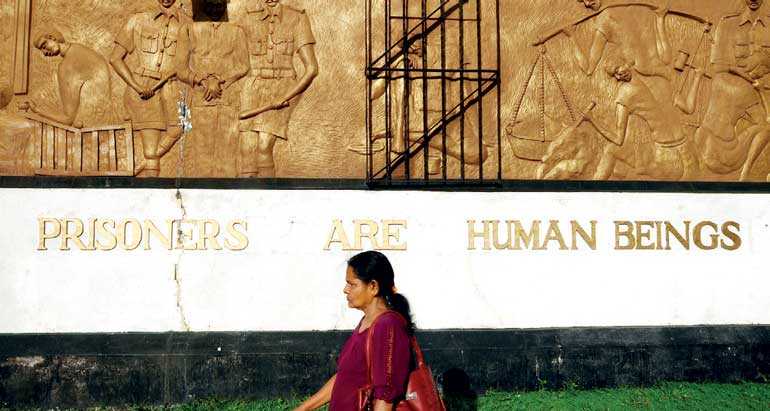

The Human Rights Commission of Sri Lanka conducted the first national study on the treatment and conditions of prisoners from February 2018 to January 2020. The findings of the report are very relevant now in light of the prisoner unrest and violence that took place at Anuradhapura Remand Prison in April 2020 and last week at Mahara Closed Prison in the context of the spread of COVID-19 in prisons.

The study was conducted over two years, with a team of up to 33 persons and data was gathered through inspections of 20 prisons under the Department of Prisons, questionnaires and interviews with over 3,000 prisoners and prison officers. Interviews were also undertaken with senior officers of the Prison Headquarters and key public officials, including the then Minister of Justice and Prison Reforms, Attorney General.

Treatment and conditions of prisoners

As per statistics, prisons are overcrowded to 107% of their capacity. The study found that prisoners live in severely overcrowded accommodation and even take turns to sleep at night, or sleep in the toilet due to the lack of space. Prison buildings are outdated and dilapidated with crumbling structures and leaking roofs, which pose a constant risk to prisoners’ lives. These structures are highly susceptible to natural disasters, and there are no disaster management protocols in place to deal with emergency situations.

Due to the level of overcrowding, sanitation facilities and water supplies are inadequate to meet the needs of prisoners. At night prisoners are locked in their cells and do not have access to the toilet, which is outside the cell. As a result, prisoners have to use plastic bags or buckets to relieve themselves and multiple prisoners in a single cell have to use the same bucket/bag.

A prisoner at Welikada prison stated, “If we want to pass faecal matter at night, we do it into a shopping bag and tie it. In the morning, we throw it into the toilet. We have to bear the bad smell overnight. In the early days, there were 11 people in my room.”

Due to poor hygiene and sanitation, a large number of pests, such as rats and mosquitoes can be a found in prisons.

The food served in prison was observed to be unappetising and even spoilt at times. Prisoners are dependent on their families to provide them with personal items such as soap and sanitary pads, as the prison doesn’t have a budgetary allocation for the distribution of such items to inmates. Prisoners cannot maintain contact with their families and legal representative because telephone facilities are not available in any prison, except for Welikada prison. The only way to communicate with the outside world is through letters or in-person visits. As a prisoner said, “We sit and worry the rest of the day. I worry about my family and how my children are not talking to me,” when referring to the anguish they feel due to long separation from their families.

The state of prison healthcare is far below the expected standard of care. Prison hospitals do not receive specialised medicine and equipment and prisoners have to be transferred to external hospitals for medical treatment. Since the transfer of prisoners to courts is prioritised over transferring to hospitals, prisoners can even miss their clinic appointments. Doctors in prison hospitals were said to discriminate against prisoners based on the offences they are suspected or convicted for, which discourages prisoners from seeking medical treatment.

Prisoners admitted to having suicidal thoughts and the tendency to engage in self-harm, indicating a high level of mental distress behind bars. In the study, 60% of male prisoners and 55% of female prisoners reported they experienced depression, anxiety and sadness to a level where it interferes with their daily tasks and everyday functioning.

Rehabilitation in prison

Although the rehabilitation of offenders is the primary stated objective of the Department of Prisons, the present system of rehabilitation barely fulfils the stated objective. For instance, prisoners are mostly involved in labour intensive and manual tasks throughout the duration of their sentence, and do not have the chance to continue disrupted public education or learn employable skills.

Convicted inmates are paid Rs. 1 per day for engaging in prison work, as payments have not been revised for decades. As a result, prisoners are released back into society without the means to earn a livelihood, suffer the stigma of imprisonment and are unable to re-integrate into society. This obstructs effective reintegration and creates conditions ripe for reoffending.

The system for early release from prison is dysfunctional and does not incentivise prisoners to reform themselves with the promise of early release on license, partly due to the lack of a standardised system of assessing prisoners’ suitability for early release. The process of commuting prisoners serving death, life and long-term sentences is also ad-hoc and lacks transparency, which leads to the risk of arbitrary decisions by the President in the release and commutation of prisoners. Long-term incarceration, without the prospect of early release as a reward for rehabilitation, is only a burden on the overburdened prison system and the taxpayer and serves no benefit to the prevention of crime in society.

Vulnerable categories of prisoners

The study found that prisoners on death row and life prisoners were more vulnerable because they are held in prison indeterminately, without an end date to their sentence. Death row prisoners are only allowed thirty minutes out of their cells/wards each day and the lack of meaningful daily activity coupled with distance from their families, impacts adversely on their mental and physical health. Death row prisoners feel they have ‘nothing to lose’ i.e. no incentive to behave well in prison because they are already serving indeterminate sentences and cannot be punished further.

Prisoners arrested under the Prevention of Terrorism Act (PTA) have spent a prolonged period of time in remand – it was reported that 11 PTA prisoners have spent 10 to 15 years in remand, while 29 prisoners have spent 5 to 10 years in remand. They are vulnerable to the constant risk of ill-treatment and discrimination from other prisoners and prison officers depending on changes in the political climate. PTA prisoners reported they were subjected to torture during the period they were held on Detention Orders following their arrest and were forced to sign confessions, which form the basis of the evidence against many of them.

Foreign national prisoners are also vulnerable because they do not know the local language and are completely cut off from their families in prison. The prison system also does not accommodate the specific needs of women in detention, such as the provision of sanitary napkins, and offers limited opportunities for rehabilitation beyond stereotypical programmes such as sewing and craft-making.

Use of violence and the working conditions of prison officers

The use of violence by prison officers for the maintenance of discipline and order was reported from all prisons visited. Prisoners said they are beaten using bats and batons and subjected to verbal abuse. An inmate stated “they treat us like dogs”. It was said that disciplinary action is not taken against responsible prison officers, which enables a culture of violence and impunity.

The lack of effective external and independent oversight of prisons prevents inmates from complaining against prison officers due to fear of reprisals. The use of violence to control distressed prisoners suffering withdrawal symptoms (alcohol/drugs) appeared to be a factor that caused deaths in prison, along with the delays in transferring prisoners for emergency medical treatment at night time.

Interviews with prison staff revealed that the high-risk work environment in which they work, the minimal salaries they are paid and the high levels of burn out and severe psychosocial distress they experience, also exacerbate the use of physical violence and verbal abuse. A study conducted by the Ministry of Health on levels of stress experienced by prison officers revealed 31.1% of prison officers suffer from burnout, 28.6% suffered from mental exhaustion and 37.8% suffered from diminished personal accomplishment.

At every prison, the administration is severely short staffed and so prison officers have to undertake multiple tasks and work overtime, often without extra remuneration. A prison officer stated: “Officers can’t go on leave. Officers have to do night duty today and go on court escorts the following morning. We work under immense pressure. It’s humanely impossible to handle this and not be angry or stressed – you have to be a saint.”

Any attempts, therefore, to re-imagine the prison system must include professionalization of the staff, training on human rights and use of minimal force and changes to their salary scale in order to reflect the high-risk nature of their work.

The criminal justice process

The penal system cannot be re-imagined without key reforms to the criminal justice process. Prisoners reported the use of violence in police custody to obtain confessions/gather evidence after the arrest. One of the reason for the protracted legal process is due to delays in the police investigation and on the part of the Attorney General’s Department and Government Analyst Department, particularly in relation to persons arrested on minor drugs charges who spend many months in remand for offences that carry small fines as penalties. This is exacerbated by the lack of legal aid and directly contributes to overcrowding in prisons.

Persons from disadvantaged backgrounds are further marginalised by the justice system. Rather than prevention of crime, the prison system pushes persons into a cycle of poverty and marginalisation. The report recommends that we need to re-imagine the prison system to ensure a safer society.