Saturday Feb 21, 2026

Saturday Feb 21, 2026

Friday, 21 May 2021 00:00 - - {{hitsCtrl.values.hits}}

The State Pharmaceuticals Manufacturing Corporation. A guileful scheme that pervaded two regimes prioritises profits over public health, and gave life to an ostensible State-sponsored private sector that has emerged more powerful than the State, statutory bodies in the Ministry of Health and the country’s legitimate private sector

By a Special Correspondent

Sri Lanka’s health sector is unwell, its vital functions deteriorating putrefied by corruption, political power-play and negligence. Governance is all but dead within. COVID-19 has done little or nothing to manifest this state of failure. Instead, the pandemic has served as a facade for protagonists with ulterior motives to consolidate their end.

This report examines the local pharmaceutical manufacturing industry; a sector laid to waste despite the establishment of a dedicated State Ministry to promote Production, Supply and Regulation of Pharmaceuticals.

A guileful scheme that pervaded two regimes prioritises profits over public health, and gave life to an ostensible State-sponsored private sector that has emerged more powerful than the State, statutory bodies in the Ministry of Health and the country’s legitimate private sector. Let us consider these events.

Catching up to others

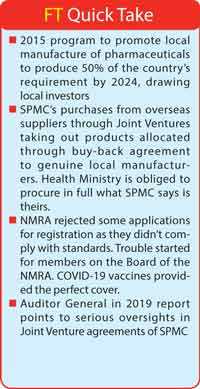

In 2015, then President Mahinda Rajapaksa introduced a program to promote local manufacture of pharmaceuticals in Sri Lanka. The program envisioned to produce 50% of the country’s requirement by 2024, drawing significant interest from local investors within the sector. This was also on account of a buy-back guarantee from Government for designated quantities, on top of potential to export.

Despotic attitudes of officials of the current regime have led to the breakdown of conventions within this program, resulting in erosion of investor confidence and substantial losses to the State. These failures also sit at the core of recent upheavals of personnel within the Ministry of Health and some of its most critical agencies.

In this instance, the Ministry of Health and the now State Ministry on Production, Supply and Regulation of Pharmaceuticals, have failed its primary responsibility; to safeguard and uplift human lives and health. The findings below bode ill for Sri Lankans and paints a dismal future for investments into the sector. The private sector too must indulge some introspection on its passive approach towards whims of self-minded politicians, to the detriment of valued stakeholders.

Pharmaceuticals, have failed its primary responsibility; to safeguard and uplift human lives and health. The findings below bode ill for Sri Lankans and paints a dismal future for investments into the sector. The private sector too must indulge some introspection on its passive approach towards whims of self-minded politicians, to the detriment of valued stakeholders.

Before 2015, Sri Lanka only produced close to 3% of its pharmaceutical requirement, with imports leading the way. Close to home, India, Bangladesh and Pakistan had evolved into major production hubs for the global pharma industry. By February 2021, India’s pharmaceutical trade was worth $ 41 billion, supplying 50% of global demand for various vaccines. It is billed to top $ 65 billion by 2024. Pakistan with just one EU GMP plant produced over $ 3.2 billion of pharmaceuticals in 2019, with Bangladesh billed to top $ 6 billion by 2025.

Local industry boom

With the advent of the new scheme, local manufacturing of pharmaceutical products got off to a sound start. At the outset, local industry supplied up to 5% of domestic requirement and by 2020 it had increased to 15%, with plans to ascent further by 2025.

With up to 100 products produced locally out of a planned 350, this program delivered significant savings to the Sri Lankan Government alongside a constant supply chain from here at home. Local manufacturers like Hemas, Sunshine Holdings, Navesta, CIC, Gamma and Astron invested billions of rupees to enhance capacity, with facilities built to European Medicine Agency’s Good Manufacturing Practice (EU GMP) standard and local GMP standards.

Medicines produced for local consumption, needs approval from the local regulator, the National Medicines Regulatory Authority (NMRA), as manufactured to standard outlined by the World Health Organization (WHO). With the buy-back agreement in place with government up to 2024 (for most companies), the local industry grew over the past five years with significant investments in technical and social capacity. Things took a ‘drastic’ turn in 2021.

Fixing by the ‘State’

The changes are founded on an existing agreement that Government had in place with the State Pharmaceuticals Manufacturing Corporation (SPMC), that the State would purchase complete stocks ‘manufactured’ by SPMC. This agreement receives priority as SPMC is a State institution. In 2010, SPMC could manufacture only 20 of the 59 products its supplies to the Health Ministry’s Medical Supplies Division (MSD). The MSD’s requirement was significantly higher than SPMC capacity. With imports dominating medicines in Sri Lanka, the 2015 program to promote local manufacturing was a game-changer for the industry.

A little after its launch, ‘Management’ of SPMC began forming Joint Ventures with local and foreign individuals and organisations to ‘jointly’ produce pharmaceuticals. These pharma products were not manufactured in Sri Lanka and instead were imported from India, Singapore, Nepal and other destinations. However, the SPMC Management ostensibly with the tacit approval of the relevant Minister misled the Government to believe these products manufactured through so-called Joint Venture programs of SPMC be considered as SPMC products, and therefore, come under the government’s agreement for mandatory purchase, a special concession granted only for SPMC manufactured products. In other words, privileges accorded to a State enterprise were abused to facilitate products manufactured by its favoured Joint Venture (JV) partners to be given priority over other local manufacturers.

SPMC’s purchases from overseas suppliers through its joint ventures have taken out a significant quantity of products allocated through the buy-back agreement to genuine local manufacturers. This invalidates the buffer of the buy-back agreement as the Health Ministry is obliged to procure in full what SPMC says is theirs. The local industry that can supply up to 45% of domestic requirement following investments to the tune of billions of rupees suddenly found itself burdened with excess capacity despite assurances provided by Government.

Adverse economic cost

Concerns over SPMC’s Joint Ventures are not limited to the identity of partners or the source of production. There is the all-important question of price and the cost of operations to Government. From the outset, during the ‘Yahapalana’ regime, SPMC’s joint venture partners placed significant mark-ups on products, but the Ministry still went ahead with purchase.

The writer was privileged to observe documents shared with the Ministry of Health, detailing resultant losses to the State from these consignments. With local industry and regulators beginning to raise apprehensions, over time, joint venture partners and the SPMC moved to reduce prices almost on par with the domestic trade. Despite differences being a mere 10 cents over local trade, one must be cognisant to the volumes involved.

The economic impact to the Sri Lankan Government and the public therein are severe. This encompasses 350-plus medicines the Ministry must procure for MSD; medicines that can be manufactured here at home for much less. A conservative estimate of 10 cents lost per 250 million tablets for 100 medicines (Rs. 2.5 billion) reveals the measure of money involved. Needless expenditure for Government and profits for a favoured group.

Obstacles no more

Pricing oversight and regulations formed the key stumbling blocks for Joint Venture partners and the SPMC in their malfeasance. Price of medicines manufactured in Sri Lanka must be approved by two pricing committees; one governing the SPMC and its Joint Ventures and another overlooking medicine manufactured by other local organisations. The current Chairman of the SPMC and his representatives sit on both committees, and in this present circumstance, construes a conflict of interest as it gives him visibility and control over ‘competitor’ pricing.

Furthermore, medicines, including those manufactured locally, require approval from National Medicines Regulatory Authority (NMRA). It was revealed in documents, the NMRA had rejected some applications for registration from SPMC, as they didn’t comply with standards of manufacture stipulated by the WHO. This is how trouble started for members on the Board of the NMRA. COVID-19 vaccines allegedly provided the perfect cover to achieve this end. COVID-19 vaccine manufactured in China ostensibly provided the perfect opportunity for the SPMC and its Joint Venture partners to achieve their objectives. The same protagonists are believed to be behind the recent changes on the Board of the NMRA.

There are numerous cases of venture partners winning tenders offering samples with ‘best possible quality for the lowest price’; propositions that cannot work in the real world. Some of these suppliers have been found providing inferior medicines unfit for consumption to the Sri Lankan public. The SPMC does not employ any stringent process of quality control. Evaluation can take well over a year at times, by when batches have expired or already consumed by the Sri Lankan public. By such time, no such company or supplier exists, but the same persons involved have turned up with new contracts from the SPMC, it was revealed. Details of this story will follow in coming weeks.

Auditor General takes note, what then?

As alluded to above, SPMC’s Joint Ventures did not manifest within the short span of this Government. It found root during the Yahapalana regime, and distended disproportionately under the sitting administration. The Auditor General in a 2019 report on SPMC Joint Ventures made the following observations.

“According to the recommendation of the Official Committee appointed by the Cabinet Ministers, quality control, management and technical assistance of the production process of the investor who had contracted for the joint venture [sic] should be provided by the Corporation and 10 per cent of share of business of the said investor should be issued to the Corporation in this regard. However, 15 drug items for Rs. 2,172.65 million and 5 items of surgical consumables for Rs. 42.41 million had been purchased from two private companies of which shares had not been issued, and sold to the MSD during the year under review.”

“The sale price should be decided adding 20 per cent profit margin to the production cost of the pharmaceuticals manufactured by the investor who had contracted for the joint venture. Out of the total production cost of the said 11 items, 13.73 per cent had been earned by the investor as a profit margin and 8.28 per cent of the invoice value had been earned by the Corporation as service charges. Accordingly, [sic] the sale price has been decided by adding 23.15 per cent of the total production cost as profit and service charges.”

“It was confirmed that cost sheets presented to the Corporation by the private company, which only the distribution was carried out without manufacturing surgical equipment were not accurate, and they were not prepared including the actual cost of production of the first manufacturer. Actions had not been taken by any responsible officer of the Corporation to get confirmed the accuracy [sic] of such cost sheets and to get confirmed the data included in the cost sheets by an independent party.”

“A process of converting public funds incurring by the Government for medical supplies to income of several intermediate companies had been implemented through the said activity. Proper supervision, guidance or administration had not been carried out by the Corporation as the man partner of the joint ventures.”

“The certificate of Good Manufacturing Practice and the license for manufacturing of surgical consumables had not been obtained from the National Drugs Regulatory Authority by an actual manufacturer of surgical consumables which had been purchased and supplied by the contracted investor to the MSD.”

What action has successive Ministers and officials at the Ministry of Health and the State Ministry for Pharmaceutical Production, Supply and Regulation taken with regards to this report?

Industry talking points

To further corroborate the above aspects, the Daily FT spoke to a veteran of the Sri Lanka Pharmaceutical Industry, who was instrumental in re-shaping local manufacturing in 2015, and provided the below perspective.

“When it comes to local pharmaceutical manufacturing, we are in a rather pathetic situation. It had functioned very well for the past seven years, but all of a sudden the SPMC with blessings of the State Minister for Pharmaceutical Production, Supply and Regulation decided to do things on their own, which is not good for any industry or the private sector.”

“Sri Lanka is a relatively small economy, and we can’t achieve scale unlike other countries despite the presence of a strong private sector. To provide scale for the private sector, this buy-back system was introduced. Agreements must be honoured. In this instance, there is no logic to remove quotas from someone with a standing agreement delivering to specification, and giving them to SPMC joint ventures. If it was taken over by government then there can be no dispute on the matter. But it was taken under the guise of government and given to someone else. The profits made ultimately don’t even remain in the country as most of these Joint Ventures have significant foreign shareholding. That doesn’t pass a good message to industry and the private sector as a whole.”

“In any industry there is a clear public and private sector. Competition is allowed and we can match or duplicate products. But that situation changes when there is a third sector; a government-sponsored or government-favoured private sector. That’s when things go out of hand, because they get the best of both worlds. They strive for profits and experience immunity of government. That doesn’t help other private sector players, because we are just building something to lose. The Government is keen to build pharma parks in Hambantota and Oyamaduwa. For these to work they need investors joining hands with existing players, and we won’t necessarily have the confidence to do it. This ultimately affects progress of the country and pharma manufacturing in Sri Lanka.”

Change how we work

Local industries must be protected in order for them to grow. This requires preferential treatment through non-tariff or non-import substitution through regulatory control or buy-back agreements. This is what transpired in India, Pakistan and Bangladesh and that is how these nations now produce up to 90% of domestic requirement and export to other countries. This is what the State Ministry of Production, Supply and Regulation of Pharmaceuticals in Sri Lanka must take note of under the government’s plan to devise creative strategies to promote local industry. In effect, this is a golden opportunity for its young State Minister towards contribute to the development of Sri Lanka.

There is hardly any purpose setting up manufacturing in Sri Lanka to supply 15% of the market. Up until local manufacturers achieve scale and build a considerable export base, the industry should have quantum that is assured with buy-back. This cannot be an indefinite solution, and to their credit the local industry had made plans to achieve 50% self-sufficiency by 2025. After that, competitive dynamics could come into play on their own.

These Joint Ventures were initiated by SPMC with privileged patronage during the previous regime, but it was administered such it did not disrupt the local private sector whilst benefiting their own. The practice permeated to the current regime on a much larger scale, backed by more powerful individuals abusing titles and associations with high office. At present, the greed of a few masquerading as SPMC Joint Ventures is beginning to destroy genuine local manufacturers who had put their faith in organic growth by reinvesting returns of their initial investments. The only outcome so far from a reported investigation into complaints was the former secretary to the Ministry of Pharmaceutical Production, Supply and Regulation was removed for following instructions passed down by the scheme’s central figures.

A passive private sector

The local pharma industry has reportedly engaged with Ministers and several Government leaders on this matter, but with no conclusive outcome. However, another discussion point is why industry did not raise questions at the very first instance the SPMC moved to create these dubious Joint Ventures. ‘We cannot change anything, if we cannot change our thinking’. When we allow an individual or group to enjoy unrestricted benefits it becomes a tenacious addiction. Sustained by friends allied to high office, the SPMC and its joint venture groups have prevailed from one regime to another in a finely twisted web, growing bigger and bolder.

Sri Lanka’s pharma industry is in a fledgling state, it needs to be nurtured to take wing and take the global stage. Whilst we cannot anticipate if it can take on the might of India and the rest of our well-entrenched neighbours, there are niches that Sri Lanka could play in. Europe is concerned of its overdependence on India in view of the prevailing pandemic, and these are advantages Sri Lanka can make use of. This does not mean Sri Lanka can bypass India, but there are many Indian companies who could use the ‘made in Sri Lanka’ tag as operations go global. However promising these prospects may seem, the local pharma industry cannot succeed unless it stands up against state-sponsored corruption that has manifest itself as SPMC Joint Ventures.

Operation successful, patient dead

In the interim, the local pharma industry is faced with limited options. With significant investments made on the ground these companies have nowhere to go. Government too needs to take note, as public funds are allegedly misappropriated to the tune of billions. Who can bell the cat?

Industry veterans averred there is a lot of pressure building within the industry, and there could come a decisive moment for the Chamber.

“People have invested their own money as well as borrowed money and there is commitment to stakeholders. We cannot operate beyond a certain point. Most of the people who have put up plants do not know what to do. There can be serious oversupply in the country like with the banking sector. But that then becomes a commercial issue.”

“We welcome further investments in the trade, even majority foreign ownership should be allowed as we need to fast-track development. But this kind of individualistic opportunistic behaviour has to stop for Sri Lanka to develop. If anyone wants to maintain this state-favoured private sector, then Government must forget the genuine private sector.”

“If all players concerned are growing, we have no argument with that. We have seldom complained, and that has been taken for granted and our aspirations for a vibrant Sri Lankan manufacturing industry shattered to pieces. If one person can take down an industry which is of national interest, then that is a huge concern for the private sector.”