Monday Feb 16, 2026

Monday Feb 16, 2026

Wednesday, 30 October 2024 00:30 - - {{hitsCtrl.values.hits}}

The way we talk about suicide plays a vital role, as it has the potential to wound or heal, disenfranchise or empower, defeat or motivate, especially for survivors of loss

The 10th of September (World Suicide Prevention Day) and the hive of activity that surrounds it each year, has gradually begun to fade; from social media, and from our collective memory. However, there are still red-hot smouldering embers, brightly ablaze in the lives of those affected by mental illness and suicide, including those bereaved by suicide loss.

The 10th of September (World Suicide Prevention Day) and the hive of activity that surrounds it each year, has gradually begun to fade; from social media, and from our collective memory. However, there are still red-hot smouldering embers, brightly ablaze in the lives of those affected by mental illness and suicide, including those bereaved by suicide loss.

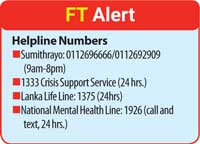

Prevention in the context of recognising warning signs and risk factors, reducing access to means and reaching out for support, helpline numbers, asking the suicide question, etc. in connection with intervention were widely discussed; in panel discussions, news articles, and social media platforms. However, a key concept discussed in the literature about suicide prevention was/is neglected; and that is postvention.

Postvention is an organised response in the aftermath of a person taking their life, where healing and recovery is promoted while mitigating negative effects of exposure. It is an integral part of prevention, where practical social support in the immediate aftermath and long-term support is offered to prevent future suicides from occurring, especially in those who are already vulnerable and are at risk. It involves acknowledging the fact that bereavement as a result of suicide might be complicated in nature, and that it would be experienced differently than when losing a loved one or a friend to other causes.

Survivors of suicide loss

Survivors of suicide loss are often left with fundamental beliefs around safety, predictability and control being shattered, and with ‘why’ questions and questions around responsibility for which seeking answers may be a challenging process. Feelings of anger and rage, guilt and shame, abandonment, groundlessness and disbelief are some of what survivors may experience, while there is a strong need to seek explanations and reasons for the death of their loved one. There is a process of profound meaning making and other existential questions that a survivor may grapple with, not excluding spiritual questions. The complex nature of suicide often means that there is no one single factor that might contribute to a person taking their life, and therefore there being no socially consensual answers. This when coupled with speculation, blame, rumours and gossip spread through mainstream media and social media, can bring excruciating pain to those bereaved by a loved one ending their life.

The grieving process that one goes through after a tragic loss like suicide, is often disenfranchised in our society, where there is no public acknowledgement of one’s grief, one’s grief may not be seen as valid, and friends, neighbours, extended family members, etc. may be unsure of how to support the bereaved, uneasy about what to say and do. The already existing stigma and taboo around suicide may cause a wall of silence to shroud the bereaved, as the initial days after a loss passes by. Therefore, effective postvention involves us staying close to the bereaved, not just in the initial phase after their loss, but for the long haul. Avoiding asking for explanations, and refraining from providing hollow reassurances like “at least they are not suffering anymore” is crucial. Acknowledging their pain, and understanding that different people may need different forms of support at different times can contribute to constructive postvention. Encouraging professional support by reaching out to a mental health professional could also be a part of postvention.

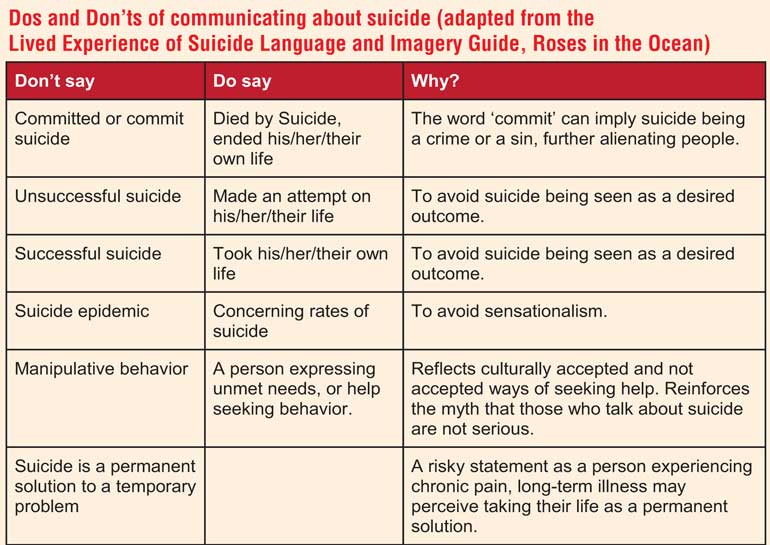

Language matters! The way we talk about suicide plays a vital role, as it has the potential to wound or heal, disenfranchise or empower, defeat or motivate, especially for survivors of loss. Roses in the Ocean, the national lived experience of suicide organisation in Australia, created guidelines for communicating about suicide through consultations with those with lived experience. Lived experience of suicide can be understood as having experienced suicidal thoughts, survived an attempt at ending one’s life, caring for someone through a suicidal crisis or having been bereaved by suicide.

Lessen the negative effects of exposure

Using non-judgmental, compassionate language when speaking about suicide, while avoiding the sharing of graphic details, images of locations, and methods can promote prevention, and lessen the negative effects of exposure. Being mindful not to provide simplistic reasons for someone ending their life, as it can put other vulnerable people at risk, is another powerful way to promote prevention through postvention. There is also a need for law-enforcement personnel, emergency medical personnel, coroners, funeral directors, hospital staff, school administrators, human resource managers, etc. to be provided training in postvention, so that they can provide immediate support to survivors of loss.

Using non-judgmental, compassionate language when speaking about suicide, while avoiding the sharing of graphic details, images of locations, and methods can promote prevention, and lessen the negative effects of exposure. Being mindful not to provide simplistic reasons for someone ending their life, as it can put other vulnerable people at risk, is another powerful way to promote prevention through postvention. There is also a need for law-enforcement personnel, emergency medical personnel, coroners, funeral directors, hospital staff, school administrators, human resource managers, etc. to be provided training in postvention, so that they can provide immediate support to survivors of loss.

A gaping hole in the narrative around prevention is the support offered to those responding to a death by suicide such as members of law-enforcement. This is an urgent need that requires attention, in order to mitigate future risk. There is also the need for robust postvention action plans for schools and organisations, so that their response can be proactive rather than reactive. Finally, posts on social media, text messages, etc. reminding people to speak up and reach out, puts the onus solely on the person needing support, whereas we all have a collective responsibility to reach in and offer support.

(The writer is a psychologist with a passion for suicide prevention. He is also a certified Question-Persuade-Refer suicide prevention gatekeeper training instructor.)