Wednesday Feb 18, 2026

Wednesday Feb 18, 2026

Thursday, 14 November 2024 00:00 - - {{hitsCtrl.values.hits}}

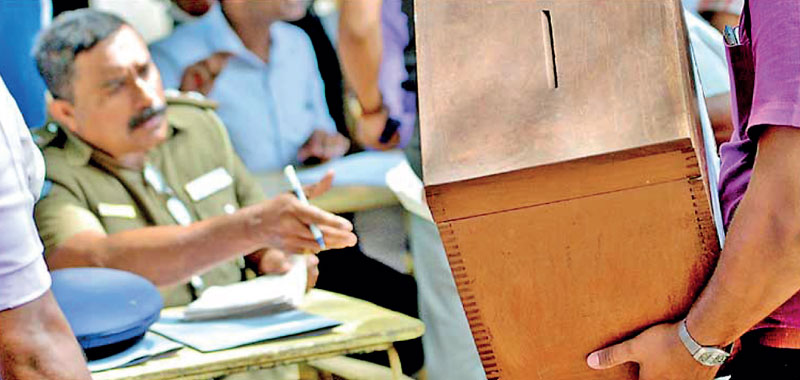

A system change will be meaningless unless governance participation is taken to the people in an effective, practical way not just during elections but in between them as well – Pic by Shehan Gunasekara

|

Government has no wealth, and when a politician promises to give you something for nothing, he must first confiscate that wealth from you -- either by direct taxes, or by the cruelly indirect tax of inflation

– John Wayne –

Politicians are the same all over. They promise to build bridges even when there are no rivers

– Nikita Khrushchev –

These two quotations, one by a famous US actor John Wayne and the other by former USSR Premier Nikita Khrushchev symbolises the reality of election promises. There are many more quotes on election promises that are appropriate to describe the fallacy of many promises made during election time, which has aptly been named the “silly season”.

These two quotations, one by a famous US actor John Wayne and the other by former USSR Premier Nikita Khrushchev symbolises the reality of election promises. There are many more quotes on election promises that are appropriate to describe the fallacy of many promises made during election time, which has aptly been named the “silly season”.

Whoever who wins the election and forms the next government in Sri Lanka will have plenty of promises to keep, if they were serious about them. The NPP manifesto released during the Presidential election was some 290 pages and that’s a lot of promises. It is an extensive document, and it presents the overall theme and program of President Dissanayake’s presidency, and it will be the guiding governance document should the NPP win the general election.

Whether the NPP forms the Government or an Opposition party or alliance forms the next government, one hopes that as a first step they will reflect their manifesto promises in strategic action plans, spread over five years indicating what they will be doing, how they will be done, who (which ministry) will be doing them, by when over the five-year period, and how funds will be obtained for implementation of their plans. If such a plan is not presented, their promises will not be worth the paper the manifestos were printed on.

Ideally, such plans should have preceded the elections and should have been integral to their manifestos so that the voters could have made a more informed decision when they voted. This not being the case, one should now look towards the future and discuss what perhaps should happen in the future.

Election promises

Two factors are relevant to the subject of election promises. Firstly, it’s not about making promises, as it’s part and parcel of a silly season, but why voters make decisions without questioning the promises, and secondly, about the lack of a methodology to hold those making promises accountable to the promises made during the silly season.

In a society that has inequality and inequity, with many having no recourse to hold politicians responsible for the promises made, except believing promises by another set of politicians at the next election and believing them, and many ending up without opportunities for their advancement due to the failings of politicians, life does not change for them except going further downhill.

The country does not have a political mechanism for people participation in governance except every five years at an election, although that participation is limited to going for or being ferried to political campaign rallies to listen to criticism of a governing party and promises about what contending parties would do, if elected. The art and mastery of public speaking rather than the substance of what is said matters at most rallies and rallies are generally extravaganzas for entertaining people and giving them imaginary hope.

A general opinion does exist today that voters are more circumspect today than they were some years back although without a mechanism in place for participation in governance, it is difficult to assess this circumspectness on the part of voters. Voters of today are probably more informed thanks to a wider TV audience and the proliferation of social media. However, this information, readily circulated by voters, is a mix of fact and fiction without any questioning of whether it is one or the other.

A change to the governance structure, a system change, therefore, should be a priority for whoever wins government on the 15th of November. The centrality of the national Parliament for governance must be questioned as its not the building on Diyawanna Oya that is important but who is inside it that matters.

It’s a much-hackneyed phrase, but very relevant to this day, is that every five years, voters become masters for a day and servants for the next five years. If governance is to improve and people are to participate in governance, this conundrum, if one could call it as such, must change.

Participation mechanism

This participation mechanism has many key elements. Firstly, it must be there to tell the truth to the people. Truth about the economy, truth about the country’s financial position. Whether it is at election time or during the interim five years, governance must be based on truth and people attuned to what is possible and what is not possible based on truth. People’s expectations should not be based on untruth.

Secondly, participation in governance should be decentralised and broad based as too much centralisation, with just a majority of the 225 parliamentarians making decisions on behalf of the entire country is not only unjust, unwise and even foolish, and recent events have shown that it has not worked for the country as well. Submitting a parliamentary bill and having them passed by a majority in parliament does not give an assurance that such bills have been passed after discussion, amendments made based on such discussions, and the implications of the bill has been considered with careful thought as to its immediate and longer-term effects and benefits to the people.

In regard to a methodology to hold those making promises at election time accountable to the people, any promise that has a direct dependency on funding should provide information on how such funding will be found to implement the promise. In this regard it is suggested that such promises, made by any political party, at a general election or at a Presidential election, should compulsorily be submitted to an independent financial body whose task should be to check the costings of the promise as well as the veracity of the estimated expenditure and the source of funding.

Admittedly, manifestos contain promises that are directed towards changes to political and social culture, as well as changes or new proposals that have a direct financial implication. An overall change to the design and content of manifestos may have to be considered to differentiate promises that have a direct and immediate financial implication and others that do not have such an implication or they are very long term implications.

Manifestos are necessary and a serious part of an election as they represent the essence of a social contract with the people who vote in a President or a government. It is therefore or should be, a legally enforceable document which should provide an opportunity for a voter to take legal recourse should an elected President or a government fails to make good on their promises to the people unless it can provide good reasons for not doing so. If the governance mechanism is based on a methodology of governance based on truth, and it is decentralised to allow greater, effective participation by the people, manifestos and the earlier mentioned strategic plans based on manifestos, could be used as resources for discussions with the people.

Finally, the question is about the mechanism political parties are willing to introduce to bring in greater accountability to their part of the social contract they have with the people via the manifestos, and are they willing to make their manifestos legally enforceable documents so that election promises are based on the truth, they are realistic, they are widely discussed and their financial implications are assessed by an independent entity accountability to the people.

A system change will be meaningless unless governance participation is taken to the people in an effective, practical way not just during elections but in between them as well.