Monday Feb 16, 2026

Monday Feb 16, 2026

Tuesday, 1 October 2024 00:04 - - {{hitsCtrl.values.hits}}

Is it reasonable for the Government to take on more debt to build tracks and commit taxpayer funds to a service that is incapable of even covering operational costs?

An outspoken activist justified his support for Anura Kumara Dissanayake (AKD) because of the superiority of the manifesto proposals on public transport, especially railways. It’s possible that the actual decision was taken on some other basis, but the railway proposals shed light on a larger problem. I had studied the manifestos in detail but paid little attention to sector proposals, considering them irrelevant in the context of the financial constraints any successful candidate would have to work within in 2024-29.

An outspoken activist justified his support for Anura Kumara Dissanayake (AKD) because of the superiority of the manifesto proposals on public transport, especially railways. It’s possible that the actual decision was taken on some other basis, but the railway proposals shed light on a larger problem. I had studied the manifestos in detail but paid little attention to sector proposals, considering them irrelevant in the context of the financial constraints any successful candidate would have to work within in 2024-29.

I rechecked the manifestos. Ranil Wickremesinghe (RW) discussed transport infrastructure relevant to the export economy briefly but made no mention of railways. Sajith Premadasa (SP) made six promises on transport, of which one was on rail (reviving the Kelani Valley light rail transport project cancelled by Gotabaya Rajapaksa). AKD’s manifesto contained eight detailed promises on railways alone, all suitable for inclusion in a wish list:

No-money promises

It is understandable that the AKD manifesto would appear attractive, especially for those who care about public transport, a sorely neglected part of the economy. But, the activist should have at least gone beyond the wish list to see whether the promises had been costed and whether the sources of funding were realistic. With a few exceptions, none of the manifesto promises had been costed by any candidate. No estimates had been provided for the massively expensive railway and expressway promises. Given the tax cuts and Government salary increases proposed by all candidates to varying degrees, there is little or no money for the required capital expenditures. And there are limits on how much debt can be taken on.

But even if there was money, is it wise to put more resources into this sector?

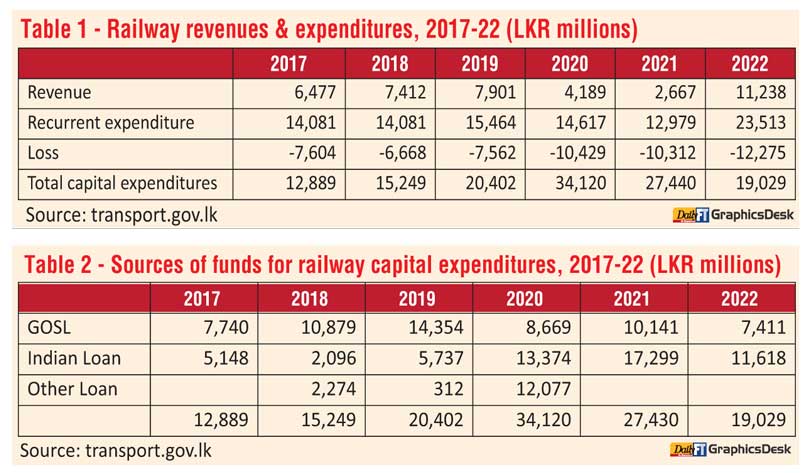

The railway is a strange business in Sri Lanka. Revenues crashed in 2020 and 2021 because of COVID and lockdowns and then increased well above the pre-lockdown levels in 2022. Anyone could see the load factors were up. This could be attributed to a shift to rail travel because of shortages and higher prices affecting the alternative modes. One would expect the losses to decrease when more revenue was generated. But instead, recurrent expenditure doubled, resulting in the largest losses since 2017. And all this without taking into consideration capital expenditures.

Even in a system like Sri Lanka’s where investments in track and rolling stock are minimal (exceptions being the Main Line to KKS and the Beliatta extension, Table 1 shows that capital expenditures, exceed recurrent expenditures in most years. If proper modernisation is undertaken, the capital expenditures should be even greater. Modernisation does not mean high-speed trains like in China. It just means not going at 15 KM/H on the Uva line, not having to use ear plugs after Polgahawela, etc. It means the quality of transport offered by the IRCON constructed new tracks on the Main Line to KKS.

Where should the money come from? Is it reasonable for the Government to take on more debt to build tracks and commit taxpayer funds to a service that is incapable of even covering operational costs? What is more reasonable is to expect at least a partial contribution to capital expenditures and/or loan repayments from operations.

Alternatives to debt-financing

The present economic realities do not justify any further investments in railways, unless satisfactory answers can be provided for the above questions. The only way that operational losses can be stanched is by reforms in the way the railway system is operated. That would mean ending the present integrated monopoly structure and changing the organisational culture that permits one or more of the many trade unions to harass and extort the government and the passengers through wildcat strikes like the unannounced strike that stranded passengers in July.

Taking on more debt without reforms is foolish. The more track is laid, greater are the losses as was the case when the Main Line was rebuilt after the war and the Southern Line was extended to Beliatta. The more passengers are carried, greater are the losses as was the case after 2022. The taxpayers bear the burdens of debt repayment. The managers and employees of the railway are completely insulated from that process and enrich themselves at the cost of the taxpayers.

Realigning the incentives of the managers and employees does not mean that all subsidies have to be stripped out. The substitute for rail transport is road transport where the taxpayers bear most of the costs of the roadway through taxes on fuel and general taxes. The profitability of a road transport company is not calculated by factoring in all the costs of the roadway and does not include the negative externalities of pollution and congestion. It would be reasonable for taxpayers to contribute to rail track investments in the form of viability gap financing.

This leads to a reform design that would separate the building and maintenance of track from train operations. The state role would be greater in track given the significant public contribution in terms of land, rights of way, etc. Ideally, some form of competition would be introduced in train operations along with private investment. The State would, of course, play a strong role in regulation and in ensuring competition is effective.

What can be done

None of the critical issues identified above are addressed in the NPP wish list or in the other manifestos. There is no money to fulfil any of the wishes. Even if there was money, it would be foolish to put it into the railway sector under the present circumstances.

Macro-economic stability is the highest priority at this time. But action to remove the constraints to growth must be started in parallel. Infrastructure reform takes time and must address multiple interacting components. Merely calling for bids to develop valuable railway land in urban centres will not suffice.

Support for reform, and even privatisation, has gone up significantly. What was said or not said in the manifestos is irrelevant. Work to develop a sector reform plan using international experience must start now.