Wednesday Feb 18, 2026

Wednesday Feb 18, 2026

Saturday, 18 January 2025 00:10 - - {{hitsCtrl.values.hits}}

I first met Sudarshan Seneviratne – or Uncle Sudarshan as he was to me – when I was around 10 years old. In retrospect, I realise I have known him my entire life. While early memories are hazy, centred mainly on his friendship with my parents, he soon made an indelible impression on my young mind in a way few adults did. Already a Professor of Archaeology at the University of Peradeniya by then, he would go on to hold the only Chair in Archaeology in Sri Lanka’s university system. Tall, charismatic, and always with a twinkle in his eye, he seemed to possess encyclopaedic knowledge spanning archaeology, history, politics, literature, music, and beyond, with a delightful sense of humour to match. A true Renaissance man.

I first met Sudarshan Seneviratne – or Uncle Sudarshan as he was to me – when I was around 10 years old. In retrospect, I realise I have known him my entire life. While early memories are hazy, centred mainly on his friendship with my parents, he soon made an indelible impression on my young mind in a way few adults did. Already a Professor of Archaeology at the University of Peradeniya by then, he would go on to hold the only Chair in Archaeology in Sri Lanka’s university system. Tall, charismatic, and always with a twinkle in his eye, he seemed to possess encyclopaedic knowledge spanning archaeology, history, politics, literature, music, and beyond, with a delightful sense of humour to match. A true Renaissance man.

Those early memories are rich with his immense love for research and teaching, and I recall stories of his late-night writing sessions in his study – a practice I would unknowingly emulate decades later. His intuitive grasp of my aspirations led him to convince my parents to buy me my first computer. Later, he helped craft my first CV at 18 – a small yet pivotal moment in my young life. The wonderful evenings spent with him, Aunty Harsha, and Shavera were filled with pure joy, made complete by Aunty’s delicious food!

Perhaps his most important legacy is his demonstration that the personal and the political, the academic and the practical, need not be separated. His career showed how rigorous scholarship could be combined with social engagement, and how cultural heritage could serve as a bridge between communities and nations. The Buddha statue he gave me when I first left Sri Lanka – a replica of an ancient piece that has travelled with me to New York, London, Delhi, Zurich, Vienna, and now Oxford – symbolises how he wove together the personal and the professional, the ancient and the contemporary

|

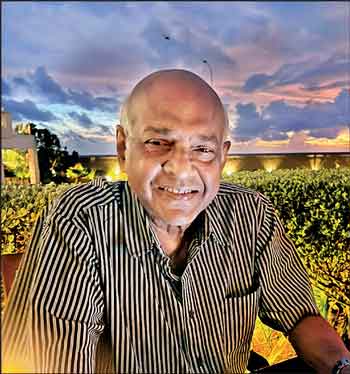

| Professor Sudarshan Seneviratne – Pic by Shavera Seneviratne |

It was during my time at the University of Peradeniya that I truly came to know Uncle Sudarshan’s essence: his intellectual brilliance, his commanding presence, and most importantly, the profound love he held for the university, his students, and his work. His office doors were perpetually open, welcoming anyone who sought his counsel – me included. Our friendship (and I hope it is the right word) deepened during our weekly journeys between Kandy and Colombo, which began with his appointment as Director of the Central Cultural Fund while I joined the University of Colombo. During these travels, we discussed everything from politics to literature to matters of my heart. Now I realise how amused he must have been by my youthful musings, yet he never made me feel small or irrelevant. Instead, he demonstrated what it truly means to listen and to care.

Our conversations continued long after those journeys ended, spanning different countries and many years. Our last one was towards the tail end of 2023. Throughout December, he had told me he was getting weaker every day, and I refused to believe it. How could the very person I had seen in Colombo just a few months ago not be in the best of health? My stubbornness was short-lived. When Shavera – his daughter whom he was ever so proud of – confirmed his declining health, I asked if I should immediately fly back home to say goodbye. ‘Remember him as the person you saw in September,’ she replied. ‘Hold onto that memory.’ When I received the dreaded message on 17 January 2024, I was left paralysed. As I had written in my doctoral thesis acknowledgments that I was immensely grateful to consider Uncle, Aunty Harsha, and Shavera as part of my family, I lost a family member that day.

In remembering him – one year later – I attempt to find the language that failed me then, to honour him as he truly deserves. In Nox, her elegy for her brother, Anne Carson writes, ‘We want to be able to say, this is what he did, and here’s why... I wanted to fill my eulogy with light of all kinds.’ Through his remarkable life and work, Uncle Sudarshan forged paths that continue to guide us today. In seeking to fill this tribute with ‘light of all kinds’, I have come to understand what he knew all along – that our most intimate bonds are also profound acts of political imagination, capable of reshaping how we understand our shared past and collective future.

Heritage as living history

Sudarshan Seneviratne’s approach to archaeology and heritage management was transformative in its emphasis on inclusivity and living history. His vision was shaped by his doctoral work under Professor Romila Thapar at Jawaharlal Nehru University, where he studied the social base of early Buddhism in southeast India and Sri Lanka. This academic foundation informed his pioneering concept of ‘social archaeology’, which viewed archaeological sites not as mere historical artefacts but as living spaces that could contribute to contemporary dialogue and understanding.

His perspective on heritage was deeply rooted in recognising the shared cultural legacy of South Asia. At the UN General Assembly in May 2011, delivering a speech titled ‘Humanism for Peace: A Buddhist Perspective’ during the Inter Faith Dialogue on International Peace, Harmony and Co-existence celebrating Vesak, he articulated this vision: ‘Though Sri Lanka represents a culture flavoured by the Buddhist ethos, there is also a legacy of a shared heritage enriched by Hindu, Islamic and Christian cultures, representing diversity and commonalities within its resident community.’ This inclusive approach characterised his work throughout his career, particularly during his roles as Senior Advisor on Culture to the Ministry of Foreign Affairs under Minister Lakshman Kadirgamar and as Director General of the Central Cultural Fund.

The Jetavana site in Anuradhapura, which is the largest existing brick-constructed stupa in the world, became a cornerstone of his archaeological philosophy. Under his leadership, what was traditionally viewed as a purely religious monument revealed itself as a vibrant testament to Sri Lanka’s multicultural heritage. The excavation yielded Hindu statues, Tamil inscriptions, and artefacts from across the ancient world, painting a picture of a thriving hub of international trade and cultural exchange. In his Himal (2008) article ‘Archaeology and the Rejection of the Mono-Country’, he emphasised this diversity: ‘The discovery of West Asian ceramics and large quantities of imported ceramics and raw material for beads only further bespeak of the multicultural and multi-religious character of the Jetavana site.’

Through innovative approaches like the ‘Public Participatory Interactive Multicultural Museum and Site Presentation’, he demonstrated how heritage sites could serve as bridges between communities. This model was pioneering for heritage site management in multicultural societies, emphasising the importance of making sites accessible and meaningful to all communities. His insistence on presenting heritage sites in all three national languages of Sri Lanka was a practical manifestation of this inclusive approach.

Heritage as diplomatic bridge

Seneviratne’s reconceptualisation of heritage as a form of soft power marked another significant contribution. His appointments as Sri Lanka’s High Commissioner to India in 2014, and to Bangladesh in 2020, allowed him to put this philosophy into practice. Having studied in India for ten years (becoming the first Sri Lankan to complete his Master’s and PhD from the Jawaharlal Nehru University), he brought a unique perspective to diplomatic relations, emphasising cultural connections and shared heritage rather than political divisions.

His understanding of diplomacy was deeply rooted in regional cultural connections. As he assertively stated in his keynote address ‘Heritage and Silent Diplomacy as Soft Power: The SAARC and IORAC’ at the International Conference on Heritage as Soft Power at the University of Kelaniya in 2019: ‘The region itself does not require third party peace merchants from outside the region or their subalterns in the region to educate us on our shared legacy and the value of mutual respect for each other.’ This perspective informed his approach to what he termed ‘Track 3 diplomacy’ – people-to-people connections built through cultural exchange and shared heritage.

His research on Indian Ocean maritime networks revealed how Sri Lanka’s position as a central hub of ancient trade routes profoundly shaped its multicultural identity. Writing in ‘Sri Lanka and the Indian Ocean in Antiquity’ (2023), he noted: ‘By the early 4th Century BCE, this island was primarily a production-distribution portal within the Rim and reached even to the Mediterranean and the Far East.’ As Executive Director General of the Indian Ocean Rim Association (IORA) Sri Lanka Secretariat, he drew on this historical understanding to strengthen cultural connections in regional cooperation.

Education and social transformation

Throughout his career, Seneviratne maintained an unwavering commitment to education as a catalyst for societal change. Writing in Himal, he expressed particular concern about the crisis in post-colonial education, arguing that the negation of liberal education had produced ‘vertically divided’ societies. His solution was to ‘humanise’ education through the liberal arts, fostering an intellectually independent next generation of South Asians.

His vision of archaeology exemplified this transformative approach. He saw it not merely as the excavation of artefacts, but as a powerful tool for conflict resolution, particularly relevant in post-war Sri Lanka. As he argued in the same article, ‘Archaeology and heritage studies are perhaps the best avenues to rectifying the process of cultural plurality, and de-mythologising all forms of parochialism in a scientific manner, by placing alternative histories before the next generation for a more rational understanding of the past.’ He consistently refused to allow archaeological evidence to be coopted for nationalist or exclusivist agendas.

His approach to mentoring was deeply personal, as I experienced firsthand. From an early stage, he shared his writings with me, engaging me in intellectual discourse that I only later realised was carefully calibrated to push my understanding further. His reading suggestions often revealed their full significance months later, demonstrating his extraordinary ability to nurture intellectual growth over the long term.

Over the years, our intellectual exchange came full circle as I began sharing my own writing with him. Though I sometimes hesitated, wondering if he would agree with my perspectives, he never criticised. Instead, he would occasionally suggest a book I hadn’t encountered, its relevance only becoming clear months later. Our final exchange was about my article for Asian Survey reviewing Sri Lanka’s tumultuous years of 2022-23. In writing about what I believed were two significant years – covering one of the biggest protests in South Asia, presidential resignations, bankruptcy, default, IMF negotiations, increasing authoritarianism, and an ongoing economic crisis – I struggled to capture the magnitude of the moment. Inspired by W.B. Yeats, I titled it ‘Things Fall Apart – Can Sri Lanka Hold On?’ His delight in this reference was palpable, and I promised to share the published version once he returned home from the hospital – a promise that would remain unfulfilled.

A legacy of light

‘Grief is a necessary component of the revolutionary imagination,’ reflects sociologist Gargi Bhattacharya about racial capitalism and personal tragedy in We, the Heartbroken. Writing this – at a time when Sri Lanka’s future shows glimmers of hope – has helped me channel my grief into remembering Uncle Sudarshan as the revolutionary intellectual he was.

His legacy lies not just in his archaeological discoveries or academic publications, but in his vision of heritage as a living force for social transformation. His approach to heritage management, emphasising inclusivity and multiple narratives, offers a model for addressing contemporary challenges of conflict and national identity. As he argued, ‘Heritage is seen as an idiom that expresses a common language of humanity where people reach out to each other for understanding, sharing and co-existence’ (Himal, 2007).

Perhaps his most important legacy is his demonstration that the personal and the political, the academic and the practical, need not be separated. His career showed how rigorous scholarship could be combined with social engagement, and how cultural heritage could serve as a bridge between communities and nations. The Buddha statue he gave me when I first left Sri Lanka – a replica of an ancient piece that has travelled with me to New York, London, Delhi, Zurich, Vienna, and now Oxford – symbolises how he wove together the personal and the professional, the ancient and the contemporary.

In a world increasingly divided by nationalism, Sudarshan Seneviratne’s vision of heritage as a bridge between communities and his commitment to education as a tool for social transformation remain more relevant than ever. His understanding of the relationship between heritage, education, and diplomacy offers crucial insights for addressing contemporary challenges of conflict and national identity. His legacy challenges us to see beyond parochial boundaries and to recognise the shared heritage that connects us all – a legacy that continues to illuminate paths forward, even in his absence.

(The writer is a Lecturer in South Asian Studies, University of Oxford, UK.)