Sunday Feb 22, 2026

Sunday Feb 22, 2026

Friday, 20 September 2024 00:24 - - {{hitsCtrl.values.hits}}

It will be wise to mark a second preference in this election – Pic by Shehan Gunasekara

Sri Lanka awaits the election of its 10th President in a political landscape that has not been seen before in history. For the first time, at least three frontrunners are contending for the presidency – as opposed to the usual bi-candidate race – with a certain possibility of none achieving an over-half majority vote. This new structure of contest has affected many socio-political dimensions of the election.

Sri Lanka awaits the election of its 10th President in a political landscape that has not been seen before in history. For the first time, at least three frontrunners are contending for the presidency – as opposed to the usual bi-candidate race – with a certain possibility of none achieving an over-half majority vote. This new structure of contest has affected many socio-political dimensions of the election.

However, in this article, we wish to focus on how the presence of more than two major candidates would affect the existing voting system and the mathematics governing its outcome. This simulation – rather than a modelling to predict the next president of Sri Lanka – is a critique of the systems designed to measure our social choice, their strengths and limitations in upholding the fundamental notions of democracy.

Voting systems

Sri Lanka has a form of ‘preferential voting’ to select its president. In this system, the candidates have to secure over 50% (50%+1) of valid ballots to become the president. This is in contrast to the ‘plurality voting system’ where each voter can mark only one candidate and the candidate with the highest number of votes wins the race, irrespective of whether they win an over-half majority. This is seen in the main elections of countries such as the USA, Canada and the UK.

A plurality system is less desirable for several reasons. First, in a closer fight between three main agents, the ballots between two ideologically similar candidates will split up, leading to the win of a third candidate who may be less popular. This ‘spoiler effect’ violates a basic principle of democracy where the preference of the majority may not be represented in the final result. Moreover, ballots that are cast on any candidate who does not win become ‘wasted votes’ in plurality vote. Consequently, it discourages people from selecting contestants who may not secure the most votes and leads to ‘strategic voting’. Citizens end up voting for either of the two candidates who are most likely to win, ultimately concentrating power to bi-partisan systems.

Preferential voting systems minimise this spoiler effect and wasted votes by allowing the voters to rank candidates according to their preferences. A variant of ‘instant run-off’ (IRV) – one of the most famous preferential voting methods – is used in Sri Lanka. The method for selecting the president if none secures a 50%+1 majority of first preferences, as per Article 94 of the Constitution and Sections 56 and 57 of Presidential Election Act No. 15 of 1981, is illustrated in Figure 1. This form of IRV is known as ‘top-two IRV’ or ‘contingent vote’ and is unique to the Sri Lanka presidential election and elections in several USA and Australian states.

Democratic power

of the second preference

Let’s imagine that among top two candidates named A and B, A has the highest number of first preferences but is disliked by the majority of voters in the country. The win by A will be prevented only if those who did not give their first preference to A or B indicate their second preference for B and that manages to offset the original lead by A. Therefore, if none secures an over-half majority, the degree to which the majority will is represented in the outcome depends on second (or third) preferences marked by those who did not vote for the top two. If the proportion of those second preferences becomes small this may reduce the top-two IRV to a plurality voting system!

This understanding highlights two of the key predictors of the presidential election outcome if a majority is not secured: 1) the original gap between the two candidates when counting first preferences and 2) the percentage of the second preferences cast by those who did not vote for the top two. The simulations to follow will show how these variables could change the next president of Sri Lanka.

This understanding highlights two of the key predictors of the presidential election outcome if a majority is not secured: 1) the original gap between the two candidates when counting first preferences and 2) the percentage of the second preferences cast by those who did not vote for the top two. The simulations to follow will show how these variables could change the next president of Sri Lanka.

Despite enabling a democratic choice, the contingent vote is not without its limitations. In the Sri Lankan system, the voters are allowed to mark only three preferences. So, if any voter fails to include either of the top two candidates within their three preferences, his ballot does not get counted in the selection of the president. This is known as ‘ballot exhaustion’. The contest of 39 candidates for the current Presidential election – the highest number in Sri Lanka’s history – increases the probability for ballot exhaustion. Moreover, when it is anticipated for none to secure a majority, there is room for a spoiler effect to occur through a discrete political deal between the third-preferred candidate and one of the top two runners.

Dynamics in casting a second preference

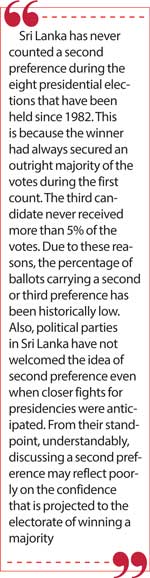

Sri Lanka has never counted a second preference during the eight presidential elections that have been held since 1982. This is because the winner had always secured an outright majority of the votes during the first count. The third candidate never received more than 5% of the votes. Due to these reasons, the percentage of ballots carrying a second or third preference has been historically low. Also, political parties in Sri Lanka have not welcomed the idea of second preference even when closer fights for presidencies were anticipated. From their standpoint, understandably, discussing a second preference may reflect poorly on the confidence that is projected to the electorate of winning a majority.

The electoral literacy of Sri Lankan voters to mark a valid ranking of preferences can also be a challenge. There were nearly 135,000 invalid votes in 2019 even when people mostly crossed in front of one candidate. This number is likely to worsen when marking preferences. Voters carry many misconceptions about casting a second preference as well. In response, the election commission, civil societies and media have already shared voting guides for the public. But there is a clear necessity for better voter education on how to mark preferences in the current election.

Ideology and second preference

Ideology and second preference

Ideologies become a major determinant in preferential voting. It is unlikely for voters to cast a second preference for a candidate who has contradictory ideologies to their first preference. In the context of Sri Lanka, more second preferences will be cast for a candidate among the top two who shares the ideologies of those eliminated candidates. This relationship – termed as ‘party effect’ – is included as the third key predictor in our simulation. However, it is important to note that ideology in Sri Lankan politics is not strictly drawn along the lines of parties or coalitions but is mingled with other social interests. The current presidential election which saw the formation of alliances between the biggest political rivals has further blurred the ideologies of its agents.

Simulating the election outcome

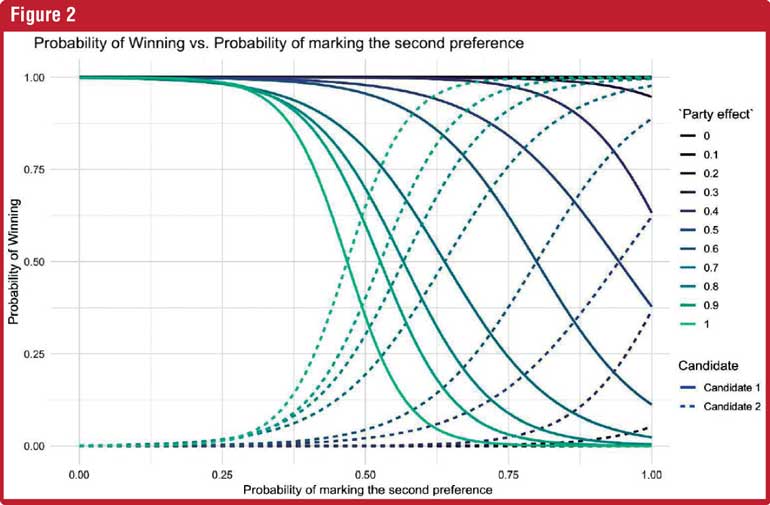

We modelled a contest where there were three main candidates with none securing an over-half majority. We used a probability distribution where each voter had a chance to vote for either of the three main candidates. In each model, we ran 100,000 simulated elections with 10,000 voters per election drawn from this distribution.

Model 1

In the first model shown in Figure 2, we kept the gap in first preferences between the first two candidates constant. Baseline percentages for Candidates 1, 2 and 3 were set at 37%, 33% and 30% based on the estimates of the latest poll by the Institute of Health Policy and after redistributing the vote percentages of other candidates among the top three. The party effect was set assuming voters of the eliminated Candidate 3 would prefer Candidate 2 above Candidate 1. A maximum party effect of 1 meant that all those voters would give their second preference to Candidate 2. Next, we changed the percentage of voters who gave a second preference for different party effects to see how the probability of winning changed between Candidates 1 and 2.

The first interesting observation was that the odds for flipping the win between the two candidates came into being only after one-fourth of voters cast a second preference! Given these baseline percentages, Candidate 2 could offset the gap in first preferences only if more than 50% of voters expressed their second preference, and that too with a moderate party effect. If the voters of Candidate 3 happened to prefer Candidate 1 for some reason (lowering the party effect), even a large proportion of second preferences in favour would not help Candidate 2 win.

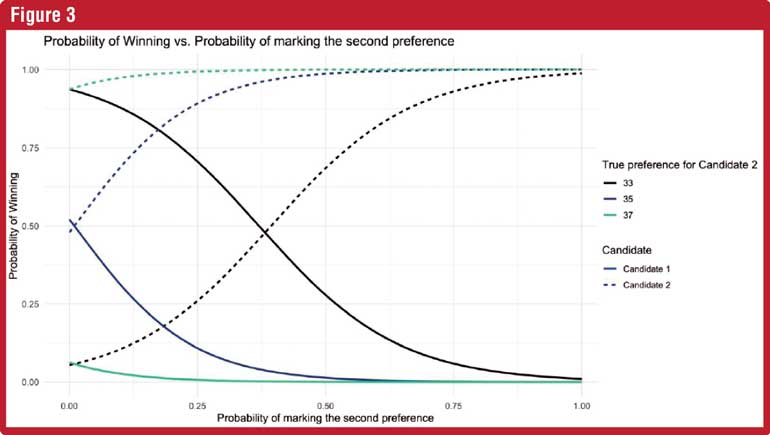

Model 2

In the second model, we kept the party effect in the same direction (voters of Candidate 3 preferring Candidate 2 to Candidate 1) and in a moderate intensity. We also fixed Candidate 3’s first preferences at 30%. Next, for different percentages of first preferences for Candidate 2, we changed the percentage of voters casting second preferences to see how the probability of winning will change for Candidate 1 and 2.

In the absence of second preferences, the drop in the percentage of first preferences for Candidate 2 from 37% to 33% drastically reduced his chances of winning the election. However, as seen in Model 1 also, even with a low first preference percentage of 33%, Candidate 2 could maximise his winning probability by increasing the support from second preferences.

So, in a nutshell, if none secures an outright majority in this Presidential election, the second (or third) preferences cast by voters will be decisive in electing the next president of Sri Lanka. It will also support a more democratic social choice by minimising a plurality vote. Therefore, it will be wise to always mark a second preference in this election. Second preference does no harm if your candidate ends up with a majority or among the top two but it will certainly matter if that expected outcome does not occur.

So, in a nutshell, if none secures an outright majority in this Presidential election, the second (or third) preferences cast by voters will be decisive in electing the next president of Sri Lanka. It will also support a more democratic social choice by minimising a plurality vote. Therefore, it will be wise to always mark a second preference in this election. Second preference does no harm if your candidate ends up with a majority or among the top two but it will certainly matter if that expected outcome does not occur.

(Dr. Inosha Alwis is a lecturer at the Department of Community of Medicine, Faculty of Medicine, University of Peradeniya. He works at the intersections of public policy and health and has a special interest in social and health choices.

(Dr. Supun Manathunga is a lecturer at the Department of Pharmacology, Faculty of Medicine, University of Peradeniya. His research interests are stochastic process modeling and Bayesian methods in medical and social data analysis.)