Friday Mar 13, 2026

Friday Mar 13, 2026

Saturday, 13 November 2021 00:00 - - {{hitsCtrl.values.hits}}

SOEs in Sri Lanka too played a significant role in rolling out the Government’s stimulus programs. This was particularly seen in sectors such as utilities, pharmaceuticals, banking and aviation where SOEs have continued their services without raising prices, and or providing moratoriums on due payments

By Imesha Dissanayake

State-Owned Enterprises (SOEs) have many definitions to it, often entailing a definition of a legal entity engaged in a commercial activity that has majority control or ownership by the country’s Government through direct or indirect means. However, because of the complex and diverse landscape of SOEs around the world, there is no longer a uniform definition of SOEs.

Globally, SOEs are present in key economic sectors accounting for 20% of investment, 5% of employment, and up to 40% of domestic output as estimated by the International Finance Corporation (IFC) in 2018. Over the last two decades, SOE’s share among the world’s 2,000 largest firms has doubled to 20%, making them a significant player in the world ecosystem.

In Sri Lanka, there are 52 strategic SOEs termed as State-Owned Business Enterprises (SOBEs), monitored by the Ministry of Finance (MoF), 87 SOEs with strong commercial aspect, monitored by the Department of Public Enterprises and 117 SOEs that are non-commercial entities, monitored by the National Budget Department. SOEs represent a key element of the Sri Lankan economy, being prevalent in strategic sectors such as energy, water, ports, banking, insurance, transportation, aviation and construction.

The 52 strategic SOBEs, represent nearly 10% of the public sector employees in 2019 and their asset base has expanded by 16.6% in 2020 on a Year-on-Year (YoY) basis according to MoF. However, the continuous losses recorded by some SOBEs and the reliance on treasury support remain a key cause of concern.

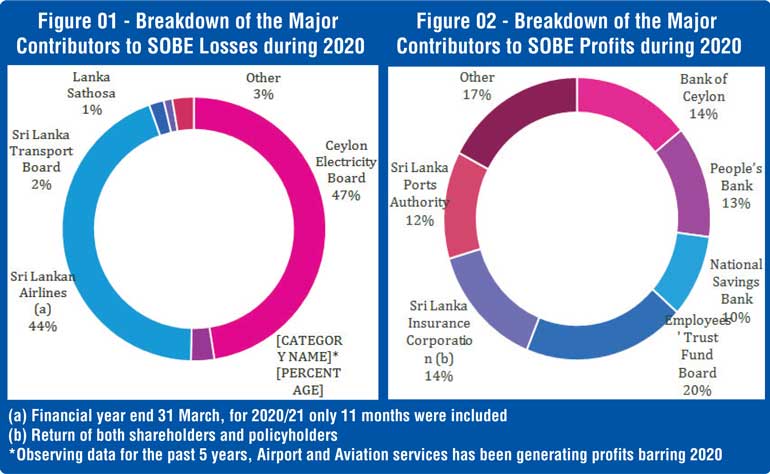

The Fiscal Management Report 2020-21 issued by the MoF, highlighted that during the first eight months of 2020, the 52 SOBEs recorded a net loss of Rs. 10 billion. However, as at end 2020, this was translated into a net profit of Rs. 34 billion with measures introduced by MoF to improve the liquidity positions of these SOBEs and the decrease in fuel bill owing to the fall in oil prices during 2020. On close examination of the profits and losses of the SOBEs, it was observed that 97% of losses were contributed by five SOBEs while 83% of profits were contributed by six SOBEs. Figure 1 and 2 provide a breakdown of the largest contributors to the profits and losses during 2020.

the 52 SOBEs recorded a net loss of Rs. 10 billion. However, as at end 2020, this was translated into a net profit of Rs. 34 billion with measures introduced by MoF to improve the liquidity positions of these SOBEs and the decrease in fuel bill owing to the fall in oil prices during 2020. On close examination of the profits and losses of the SOBEs, it was observed that 97% of losses were contributed by five SOBEs while 83% of profits were contributed by six SOBEs. Figure 1 and 2 provide a breakdown of the largest contributors to the profits and losses during 2020.

Role of SOEs during the pandemic in 2020

SOEs around the world have been one of the significant contributors to governments’ stimulus programs. The advantage of having state presence in sectors is that an immediate shift in products or services can be allocated to meet emergency needs and relief measures unlike in a free market. Drawing from countries’ experiences during the pandemic, the public utilities of most countries have expanded their services without raising prices or at zero cost to consumers.

Similarly, governments in Brazil, Canada, Germany, and India have directed their public banks to assist in alleviating the impact of the pandemic. In countries such as Indonesia and China, the governments have also taken drastic steps in converting their SOEs into producers of emergency supplies such as ventilators and face masks.

This, however, can be a source of distortion with the lack of competitive pressures to improve efficiency and can have knock-on effects on the whole economy. Based on a survey carried out by the World Bank with a sample of 482 COVID-19 related aid packages approved across five continents (as at July 2020), the total approved state aid amounted to around $ 7 trillion. Out of this, 4.6% targeted support was allocated to SOEs in order to continue their operations. Therefore, if an SOE had poor performance and badly run balance sheets at the start of the pandemic then it would have acted as a burden rather than as a buffer for economies during the pandemic.

SOEs in Sri Lanka too played a significant role in rolling out the Government’s stimulus programs. This was particularly seen in sectors such as utilities, pharmaceuticals, banking and aviation where SOEs have continued their services without raising prices, and or providing moratoriums on due payments. This may have further aggravated the economic and fiscal costs of COVID-19 for the country. Hence, managing the performance of SOEs becomes a critical factor when recovering from the COVID-19 crisis and lingering debt crisis.

In 2020, net profit generated by SOBEs increased by Rs. 30 billion when compared to 2019, together with treasury support for SOBEs growing at over 50% to Rs. 75 billion. This increase in treasury support offsets the profits generated by the SOBEs with a net negative impact of Rs. 41 billion on the treasury. Levy and dividend transfers from major SOEs that goes into the Government coffers, too declined significantly by 35% and 43% respectively during 2020. This was owing to the treasury refraining from enforcing excessive levies, in order to infuse more liquidity into SOEs.

The State-Owned Banks played a vital role in implementing moratoriums and the credit relief scheme introduced by the Central Bank of Sri Lanka (CBSL), to support the businesses that were affected by the pandemic. This has resulted in a drag on the Banks’ profitability. SOEs such as Sri Lankan Airlines (SLA), Airport and Aviation Services and Sri Lanka Transport Board (SLTB) who continued their services amidst COVID-19 too have seen a decline in their profitability with a decline of 23%, 125% and 226% respectively.

Treasury also provided financial support of Rs. 28 billion and Rs. 13 billion to SLA and SLTB respectively. Therefore, the financial viability of SOEs remain crucial in order to continue their services without being a drain on the treasury and intensifying costs of the pandemic to the country.

However, it should be noted that SOBEs such as Ceylon Electricity Board (CEB) and Ceylon Petroleum Corporation (CPC) have benefitted from the low crude oil prices seen globally during 2020. SOEs such as Lanka Sathosa have also benefited from the sales growth in essential goods during the COVID-19 pandemic.

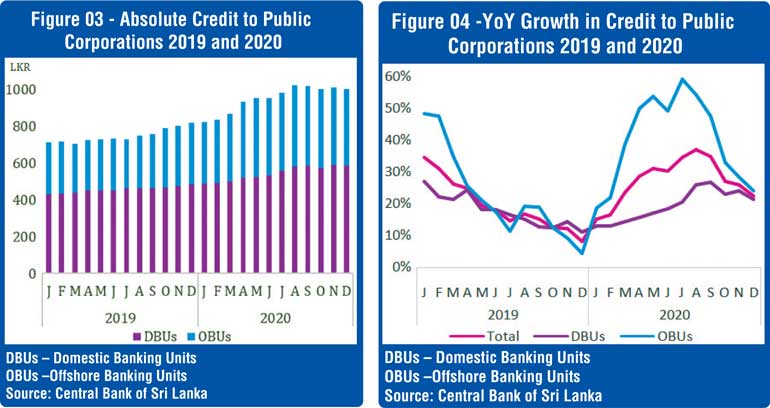

The increase in cost for SOEs during the pandemic can be further explained by the escalation of borrowings by SOEs from banks. Total credit that was directed to SOEs as at end 2020 rose by 23% YoY to Rs. 1,002 billion with a notable growth in foreign currency borrowings (24%). The CBSL annual report (2020) attributes this credit growth, to SOEs such as Road Development Authority, National Water Supply and Drainage Board, Paddy Marketing Board, CPC, SLA, SPC and CEB.

Therefore, given the country’s current position in terms of its debt obligations, it would not be sustainable for SOEs to be contributing to public sector debt and instead will need to be looking at avenues to enhance its position to improve Government finances.

Importance of SOE reform

SOEs worldwide have a growing global reach with assets valued at $ 45 trillion in 2018, which accounts for about half of global Gross Domestic Product (GDP) when compared to $ 13 trillion in 2000 according to International Monetary Fund (IMF). This outreach of SOEs can either exacerbate economic challenges or create significant value creations for countries. Therefore, SOEs around the world face strong pressures to improve their performance.

Similarly, for Sri Lanka, the presence of SOEs in strategic sectors of the country is proof of the significant value creation it can generate through spillover effects. The societal returns too are greater as it links to our day-to-day activities such as the water we drink, the electricity we use, or even the bus or train we ride.

The total revenue of the 20 largest SOBEs, was identified by MoF in 2019 to be almost 60% greater than the revenue recorded by the entities under the S&P SL 20 Index of the CSE. The total turnover of the 52 SOBEs too was significant in 2020, amounting to Rs. 1,804 billion, which was about 1.5 times the total Government revenue collected in 2020. However, in 2019 (pre-COVID), 88% of the total profits generated by SOBEs were by seven entities only while 93% of losses were by three entities, indicating that there is room for improvement in terms of its efficiency and profitability.

Hence, focusing on improving efficiency and profitability can increase Government revenue and ease revenue collection for the Government. The IMF too has estimated that globally, better utilisation of public assets can add additional public revenue equal to 3% of GDP.

Tools available for SOE reform

Optimising the performance of SOEs can be the best course of action the Government can follow to enhance Government revenue and, improve value creations for both the society and economy, especially given the COVID-19 context. An array of options is available for the Government to take on board in order to improve the performance and effective product or service delivery of SOEs to catalyse the country in the post-pandemic era. Below provides a brief overview of these possible solutions that can be implemented to optimise SOE performance (refer the full report for more details and the current state these are at in Sri Lanka).

Performance management is a tool that ensures a set of individual activities that are aligned to an organisation’s goals are achieved in an effective and efficient manner through periodic monitoring and evaluation. Therefore, developing a sound performance management system will ensure that SOEs will achieve its intended results.

A board bears the ultimate responsibility for stewardship and performance of SOEs; hence, its composition and functioning have a significant impact on the SOE’s operational and financial performance. Hence, improving the composition of SOE boards through a robust and transparent process will lead to improved SOE performance.

A regulatory authority is a body responsible by exercising regulatory and monitory measures to prevent market failures, restriction or removal of anti-competitive practices, and promotion of public interest. Strengthening regulatory authorities will ensure regulation of SOEs and optimise its performance.

Divesting SOE ownership by listing on the capital market will lead to improved accountability and transparency of SOEs owing to the listing requirements. Listing will also be an avenue for the Government to tap into public funds while maintaining Government control.

This refers to a holding company for SOEs that act as a central coordinating agency charged with monitoring performance and ensuring governance practices across the SOEs. A holding company could also act as a buffer against future pandemics and assist the Government in its relief measures.

Way forward

The above-mentioned tools would provide the necessary restructuring for SOEs to enhance their financial viability and effective product or service delivery. Sri Lanka has undertaken certain reform measures to improve SOEs’ performance. This is a good first step in this regard but building on it is vital as SOEs can be significant social and economic value creators, since, most Sri Lankans encounter these on a daily basis. SOEs can also aid the Government to reduce its debt burden and improve its fiscal performance.

Improvements in all these areas will ultimately lead to higher economic growth while also achieving the country’s development goals in the post-pandemic era. However, the success of SOE reform will rely on the SOE’s ability to be agile and respond rapidly to changes in the environment, similar, to the agility we saw during the outbreak of COVID-19 where the immediate shift of SOE resources was observed to meet emergency demand and relief measures.

(Full report can be accessed at – SOE Reform: the Impetus for Post Pandemic Economic Revival)

(The writer is a Research Associate attached to the Economic Intelligence Unit of the Ceylon Chamber of Commerce. This article is part of the Strategic Insight Series, which focuses on key contemporary topics that matter to the private sector. Topics such as Renewable Energy, REITS, Online Payments and FinTech Regulatory Sandbox amongst others have been covered by the briefs to date.)