Sunday Feb 15, 2026

Sunday Feb 15, 2026

Thursday, 3 September 2020 00:00 - - {{hitsCtrl.values.hits}}

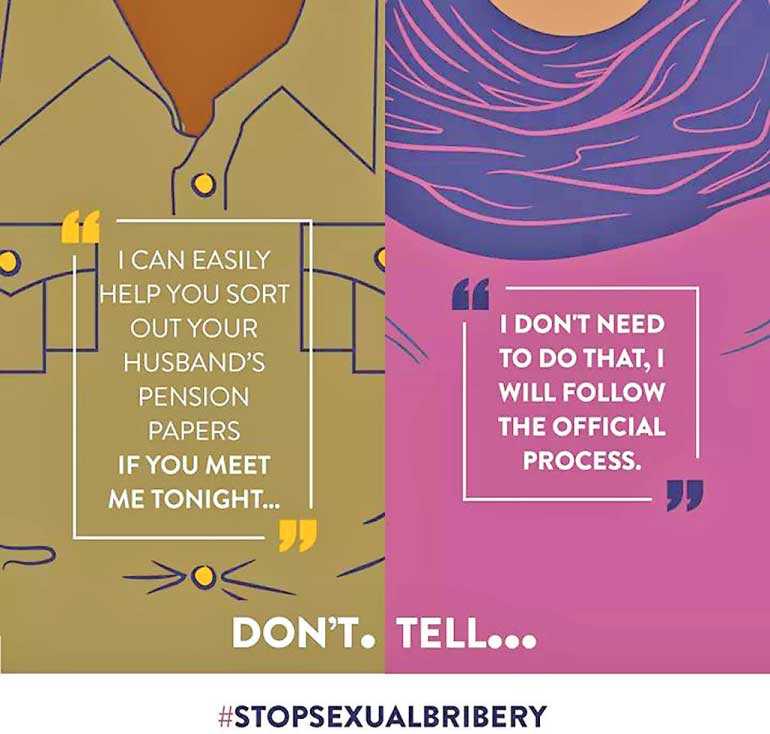

The cultural and societal perceptions surrounding sexual bribery and the treatment of victim survivors makes it more challenging for them to come forward with their stories and for justice to be met – Pic by Shehan Gunasekara

When public officials demand cash or favours to perform their duty we understand that these are bribes and that the officials in question are corrupt. What if the demand was of a sexual nature instead? Is it corruption? Sexual exploitation? Can it be categorised as a bribe?

Much like monetary bribes and other forms of corruption, sexual bribery extends to everyday transactions. However, it is rarely discussed due to unfamiliar terminology and vague interpretation. This makes it difficult to identify and understand, consequently resulting in a very low rate of reported offences. From 2010-2019 only 13 cases have been reported to the Commission to Investigate Allegations of Bribery or Corruption (CIABOC), with only six being prosecuted1.

The Centre for Equality and Justice (CEJ) has been active in researching and documenting this issue among war affected female heads of households. Their working definition of the offence is an “improper benefit” that is sexual in nature, demanded from a person by persons in positions of power in exchange for a service.

Sexual bribery has always remained in the background of other forms of corruption due to the lack of clarity and awareness around it. The cultural and societal perceptions surrounding sexual bribery and the treatment of victim survivors makes it more challenging for them to come forward with their stories and for justice to be met. “He did not force her. He only suggested, so he’s not at fault” is what Madhuri’s neighbours said when she shared her experience of being sexually propositioned by her local government officer.

CEJ has found that women who are heads of their households or without a male figure in their lives are the most susceptible to sexual bribery. Community and social criticism, traditional patriarchal values and their vulnerable position add to the notion that women are to blame for such advances or that they must accept them. The idea that sexual bribery is a secondary form of abuse that goes against law, fundamental rights and is a tool of corruption is still a vague concept that many cannot grasp. For Madhuri, the situation was problematic and confusing. She knew that his request was wrong and unlawful but did not know how to assert her rights without provoking the officer on whom she was dependent on to receive her family’s much needed documents.

Most Sri Lankans are unaware of their rights and the legal implications of this offence. Sexual bribery can be brought up under the Bribery Act (No. 2 of 1965) although there is no express provision. The definition for gratification in the law as it stands does not extend to those of a sexual nature, despite covering other forms of bribery from money, loans, gifts, etc. Several suggested amendments have been presented for consideration in recent years and CEJ’s advocacy has led to a working definition for gratification and sexual forms of gratification. This working definition has been accepted by the CIABOC and has been added to the National Action Plan for Combating Bribery and Corruption in 2019.

The CIABOC has also established a reporting mechanism for individuals to lodge a complaint either by calling them on their hotline – 1954 or reaching them on their website –https://www.ciaboc.gov.lk/contact/complaints.

However, in order to create zero tolerance for sexual bribery the reporting system should be facilitated by officers who are trained to handle sensitive cases such as these in order to instil trust and faith in the mechanism and to ensure accountability of the public service sector.

In 2019, the National Action Plan to Combat Bribery and Corruption in Sri Lanka was initiated by the CIABOC with the aim of combating corruption on a large scale. This proactive measure has continued with President Rajapaksa’s election manifesto of upholding a corruption free public service sector and holding accountable those who misuse their office. Organisations that provide training to government and private sector bodies such as Sri Lanka Foundation Institute (SLFI), and Sri Lanka Institute of Development Administration (SLIDA) should include modules on how to combat sexual bribery in their anti-corruption training modules.

Understanding and creating awareness around sexual bribery is essential to Sri Lanka’s effort towards combating this issue and maintaining a public sector that upholds accountability, identifies and prevents all forms of corruption. Until sexual bribery becomes part of the ‘corruption’ conversation, there will always be a missing piece to the corruption puzzle restricting the recognition and ability to address its full extent and impact.

*Names have been changed to protect privacy

Footnote

1https://www.pressreader.com/sri-lanka/daily-mirror-sri-lanka/20191217/281784220985785