Sunday Feb 22, 2026

Sunday Feb 22, 2026

Friday, 3 May 2019 00:00 - - {{hitsCtrl.values.hits}}

By Zahrah Imtiaz, D.B. Subedi, and Muttukrishna Sarvananthan

www.eurasiareview.com: Sri Lanka is once again in the spotlight of the world; regretfully for ugly and vile reasons. This is Sri Lanka’s 4/21 moment (ala 9/11 in the USA and 11/26 in India).

The Easter Sunday massacre of gigantic proportions (253 dead and still counting among a total population of around 21.5 million in the island nation) calls for genuine soul searching as regards how the people of this island nation should arise from this tragedy.

The National Thowheed Jamath (NTJ) – a local group of radicalised followers of Islam – is thought to be the perpetrator suspected to be acting with support from the ISIS. While it will take time for a full investigation of the massacre, it is now time for genuine soul searching as regards how the people of this island nation should arise collectively from this tragedy.

In this article, we argue that countering violent extremism in the long-run will require adopting a ‘soft approach’. Unlike a ‘hard approach’, also known as ‘kinetic approach’, which overwhelmingly relies on the use of force and stringent enforcement of the law, a ‘soft approach’ requires engaging the peoples across ethno-religious divides to counter violent extremism. This requires, first and foremost, to de-securitise ethnic and religious identities and helping the country to stand united socially and politically to prevent terrorist violence in the future.

Impacts on social foundation

Historically, religious and ethnic diversity has been the social foundation of Sri Lanka. The country is endowed with four considerable ethnic and religious groups.

The Sinhalese constitute almost 75% of the total population of which little over 70% are Buddhist and less than 5% are Christian. The Tamils of North and East make up little over 11% of the total population in which almost 9% are Hindus and little over 2% Christian. The Muslims, also known as the Moors, constitute over 9 % and are all followers of Islam. The hill-country Tamils constitute a little over 4% of the total population, of which over 3% are

Hindus and less than 1% Christian

(www.statistics.gov.lk/PopHouSat/CPH2011/Pages/Activities/Reports/SriLanka.pdf).

Despite ethnic and religious differences, bulk of the Sri Lankan Muslims speaks the Tamil language with some Arabic influence.

It is said that it takes years to build trust but just a moment to break it. In business parlance, it may take months or years to win a customer, but just a second to lose one.

For years the Sri Lankan Muslims (or ‘Moors’ in terms of the Census category), a minority within a minority, have eagerly tried to prove themselves to be like Caesar’s wife, above suspicion. During the nearly three decade civil war, they chose to side by the Government and fight against the separatist movement in the country. Until now, the Muslim minority community has been at the receiving end; subjected to violence and ethnic cleansing by especially the Tamil Tigers (formally known as Liberation Tigers of Tamil Eelam) http://www.uthr.org/Reports/Report7/chapter2.htm https://groundviews.org/2010/03/02/citizens-commission-expulsion-of-the-northern-muslims-by-the-ltte-in-october-1990/. And yet on the just past Easter Sunday of 2019, the community now finds itself under the microscope.

In a country where ethnic and religious identities are deeply overlapped, the heinous terrorist violence of 4/21 is likely to adversely affect already fragile and often tense inter-ethnic and inter-religious relations. Therefore, any effort to dealing with the extremist elements and bringing justice to the victims and their families must aim to enhance social cohesion as a potential force to fight terrorism. Experience from countries like Pakistan, Afghanistan, Syria, among others, have clearly shown that social and political cleavages provide fertile ground for terrorism to grow and sustain.

De-securitise the collective identity of Muslims

For the Muslim community in Sri Lanka, the attacks on Easter Sunday will have far-reaching consequences. As the shock of what happened wears off, they will find that the trust they had built with their fellow citizenry, especially with the majority Sinhalese community, has been cracked.

Despite the assurances from all quarters that we cannot treat all ‘Muslims as terrorists’, many will do just that prompted by the post-4/21 paranoia. And it is here that the Muslim community has to practice more restraint and patience. As their faith and practices come into question, they would not only be called into defend it but also look within and search for answers for some hard questions.

These questions have been ignored for the last several decades, opening the path to radicalisation and into violent extremism in the country. They are: Has the Muslim community truly insulated itself away from the majority community? Has the Muslim community allowed extremist ideologies to creep into the faith and tolerated them as they grew? And how can the community now start setting things right in ways it prevents radicalisation and violent extremism?

Time will find answers to these questions. More importantly, Muslim religious, social, and political leaders must come forward to work with other ethnic and religious communities to better understand the processes of religious radicalisation taking place within their community as well as within other ethnic and religious communities in the country.

The Government should desist from adopting a hasty short-sighted strategy to counter terrorist violence by the use of excessive force. Instead, understanding the Muslim community and their commitment to peace and harmony is crucially important to distinguish between peace-loving Muslims and the tiny proportion of extremist elements within the community.

The Sri Lankan Muslim community is not a monolith and thus a blanket solution for all will neither be accepted and nor will it work. Whilst it is natural to expect individuals from non-Muslim communities to be angry at the Muslim community in the aftermath of these attacks, it is imperative to note that further antagonism and discrimination would only push the Muslims away and discourage any reform within the community.

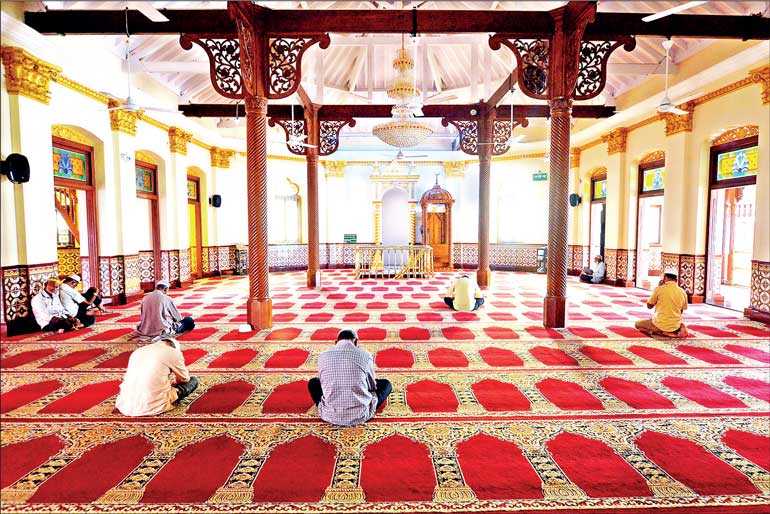

Whilst extremist ideologies have to be rooted out, the community must also feel that they are all in it together, to fight terrorism and not having to constantly legitimise their faith. The sense of retribution and fear are already high with hundreds of Muslims in the Western Province taking refuge in Mosques and police stations as a result of physical intimidation.

The emerging call to ‘return to arms’ is counterproductive

One spectrum of the emerging public opinion is a ‘call to arms’; back to the dark last phases of the civil war between January 2006 and May 2009 and its aftermath until the end of 2014, trampling on freedom, human rights and dignity, and democracy. The emerging call for return to authoritarianism, banning of this and that (e.g. the organisation/s suspected to be responsible for the heinous crime, burqa/niqab), and the sermons of parochialism and populism, which are back in vogue, must be countered with evidence and resolute.

The proposed ‘hard approach’ to deal with terrorism will only result in securitisation of the Muslim community and their religious identity and perhaps result in more reciprocal radicalisation in all sections of the society. A government, of course, can ban an organisation or a dress; but cannot ban an ideology. A ‘return to arms’ may serve narrow political opportunism in the short-term, but at the cost of deeper polarisation of the Sri Lankan society in the longer-term.

Imperative to prioritise socio-economic and cultural development

We would argue that retribution never ensures human security and enduring peace among fractured communities. The purported claim of the perpetrators of inhumanity that, no faith other than theirs is worthy of human life is hollow. This is because there is ample evidence that throughout the world they have killed more people of their own faith than that of other faiths in countries like Syria, Iraq, Afghanistan, and Pakistan, for example. The persons who call for retribution should remember the foregoing irrefutable fact; terrorists have no faith/religion other than murder.

It will be misleading to think that radicalisation, especially of youths, is an outcome of ONLY the misinterpretation of religious texts and adherence to a false ideology. Often, underlying socio-economic and cultural factors also trigger radicalisation that results in violent extremism.

Therefore, it is imperative to address the economic, social, and cultural factors that could potentially trigger radicalisation, which results in violent extremism. In spite of the very impressive human development indicators of Sri Lanka as a whole, two of the minority ethnic groups, viz. Muslims and the hill-country Tamils, are generally/mostly lagging behind the majority Sinhalese community and the largest minority group, viz. the Tamils of North and East Sri Lanka, in terms of almost all the human development indicators, including life expectancy, literacy, and educational attainments. http://www.lk.undp.org/content/srilanka/en/home/library/human_development/national-human-development-reports/NHDR2014.html

Therefore, the Government should implement an affirmative action plan to improve the literacy rates and educational levels, inter alia, of the Muslim and hill-country Tamil communities, especially that of women of these communities. The increase in educational levels of the Muslims in general, and that of Muslim women in particular, would go a long way towards luring the Muslim youth away from violent extremism because they would be less susceptible to brainwashing by terrorist elements.

Although the suspected masterminds of the Easter Sunday massacre appear to be well-educated and from a reasonably affluent family, raising the educational standards of the Muslim community as a whole has the potential to reduce the propensity for violent extremism within that community.

Reform the customary personal laws

Another critical policy measure that requires urgent attention of the Government (and indeed the Muslim community itself) is to reform the customary personal laws of all ethnic groups, especially that of the Muslim community. The Muslim Marriage and Divorce Act (MMDA https://www.lawnet.gov.lk/1948/12/31/marriage-and-divorce-muslim-3/) and the Muslim Law of Inheritance (https://www.lawnet.gov.lk/1948/12/31/muslim-intestate-succession-3/) are profoundly discriminatory towards the women of this community. It is more or less discriminatory in the same way as the Thesawalamai Law of the Tamils of North-East origin (https://www.lawnet.gov.lk/1947/12/31/thesawalamai-pre-emption-4/) and the Kandyan Customary Law of the Sinhalese (https://www.lawnet.gov.lk/1948/12/31/kandyan-law-3/) are.

For example, the MMDA legitimises child marriage among the Muslim community, which in turn results in underage marriages and higher birth rate among that community, and the consequent impoverishment of the majority of that population; such impoverishment is a breeding ground for violent extremist ideologies. The underage marriages and the consequent higher birth rate are essentially a cultural issue.

The Muslim politicians, who are almost entirely male, should proactively propose these reforms to the MMDA and other discriminatory customary laws to the Government of Sri Lanka. The rights of all human beings are universal and there cannot be any exemptions in terms of religion, ethnicity, gender, or any other division of humanity.

Promote moderate forms of Islam

Sri Lankan Muslims overwhelmingly belong to the Sunni Muslim sect. The spread of ultra-orthodox Salafist/Wahhabist forms of Sunni Islam in Sri Lanka since the 1980s, especially in the Eastern Province, had gradually radicalised considerable Muslim youths. Therefore, in order to counter the preaching of radical forms of Islam, the Government in collaboration with the Muslim community should promote moderate forms of Islam. Moreover, Muslim women should be proactively inducted to preach and teach Islam, like in Morocco (https://smallwarsjournal.com/jrnl/art/moroccos-unique-approach-countering-violent-extremism-and-terrorism). The Muslim religious bodies (such as All Ceylon Jamiyyathul Ulama http://www.acju.lk/) should be convinced to undertake these reforms.

Unite politically and socially

Having been emerging from decades of armed conflict that tore the country apart ethnically and politically, the social fabric of Sri Lanka has become rather fragile in the absence of substantive post-war reconciliation. The 4/21 terrorist violence targeting the minority Christians (most of the victims were Tamil Christians both in the Batticaloa and Colombo churches) has taken place in a social context where Muslim community was being targeted virulently, and at times violently, by hardline Buddhist ideologues since 2012.

However, it is important that Sri Lanka must overcome social and religious fragmentations and confrontations and remain socially united to recover from the terrorist violence. It is also for this reason that the efforts to deal with violent extremism and terrorism must involve a soft approach that helps to forge much needed inter-religious and inter-ethnic cooperation and collaboration.

Ethnicity and religion have always been highly instrumental in mobilising and stoking the voter base in Sri Lanka. As the country is preparing for the upcoming elections, there would be a temptation among the political parties both in the Government and Opposition to stoke the electorate by trumping up anti-Muslim sentiments, which are already rising among the non-Muslim communities.

This kind of political opportunism, which is not unlikely in the current situation, will only undermine social cohesion and create a favourable condition for reciprocal radicalisation across religious faiths. If parochial political interests and actions further deepen religious and ethnic fragmentation, it will push the country into a new cycle of conflict and violence.

Therefore, to end with a positive note, the carnage of 4/21 could also teach a lesson for peace and reconciliation and help address the social, economic, and cultural drivers of violent extremism. To do this effectively, any responsible government of today, or that of the future, should desist from contemplating irrational, knee jerk, and/or shortsighted policy measures, and instead propagate rational, fair (to all citizens), and durable policy solutions to the multiple crisis facing Sri Lanka, including peaceful and rights-based ways and means to counter violent extremism and terrorism.

[Zahrah Imtiaz, M.Sc. (Sydney), B.Sc. (Sydney), is a Journalist by profession and a Research Associate at the Point Pedro Institute of Development, Sri Lanka. [email protected].]

[D. B. Subedi, Ph.D. (UNE), M.Sc. (CEU), is a Postdoctoral Research Fellow at the School of Humanities, Arts, and Social Sciences at the University of New England in New South Wales, Australia. His current research project studies the rise of nationalism, populism, and extremism in South Asia. He is the author of the book Combatants to Civilians (Palgrave 2018). [email protected].]

[Muttukrishna Sarvananthan, Ph.D. (Wales), M.Sc. (Bristol), M.Sc. (Salford), B.A. (Hons) Delhi, is a Development Economist by profession and the Founder and Principal Researcher of the Point Pedro Institute of Development, Point Pedro, Northern Province, Sri Lanka. He is the author of ‘Terrorism’ or ‘Liberation’? Towards a distinction: A case study of the armed struggle of the Liberation Tigers of Tamil Eelam (LTTE). https://www.universiteitleiden.nl/binaries/content/assets/customsites/perspectives-on-terrorism/2018/2018-02/01-terrorism-or-liberation-towards-a-distinction-a-case-study-by-muttukrishna-sarvananthan.pdf [email protected].]

(Source: https://www.eurasiareview.com/01052019-sri-lankas-4-21-moment-a-way-forward-to-countering-violent-extremism-oped/)