Thursday Feb 19, 2026

Thursday Feb 19, 2026

Monday, 23 December 2024 00:43 - - {{hitsCtrl.values.hits}}

The IMF deal marks the beginning, not the end, of its journey

|

Sri Lanka stands at a crossroads. The successful conclusion of the IMF’s first review under the Extended Fund Facility (EFF) arrangement has been heralded as a moment of cautious optimism. For a country battered by an unprecedented economic crisis, this milestone offers a much-needed lifeline—a chance to stabilise, rebuild, and restore confidence in its battered economy. Yet, as history has shown us, an IMF deal is not a guarantee of recovery; it is only the first step on a long and arduous journey.

Sri Lanka stands at a crossroads. The successful conclusion of the IMF’s first review under the Extended Fund Facility (EFF) arrangement has been heralded as a moment of cautious optimism. For a country battered by an unprecedented economic crisis, this milestone offers a much-needed lifeline—a chance to stabilise, rebuild, and restore confidence in its battered economy. Yet, as history has shown us, an IMF deal is not a guarantee of recovery; it is only the first step on a long and arduous journey.

The deal brings immediate relief. The IMF’s disbursement of approximately $ 330 million provides critical liquidity to shore up reserves, stabilise the currency, and support much-needed reforms. This injection of confidence is equally vital, signalling to international investors and creditors that Sri Lanka is serious about restoring macroeconomic stability. But optimism must be tempered with realism. Sri Lanka’s economic recovery depends on hitting stringent targets for fiscal consolidation, debt restructuring, and institutional reform—all of which require political will and long-term vision.

For Sri Lanka to succeed where others have stumbled, the Government must prioritise both performance and prudence. This IMF program offers a blueprint, but its implementation will determine whether the country can break free from its economic malaise or spiral into further hardship.

Economic implications: Numbers that matter

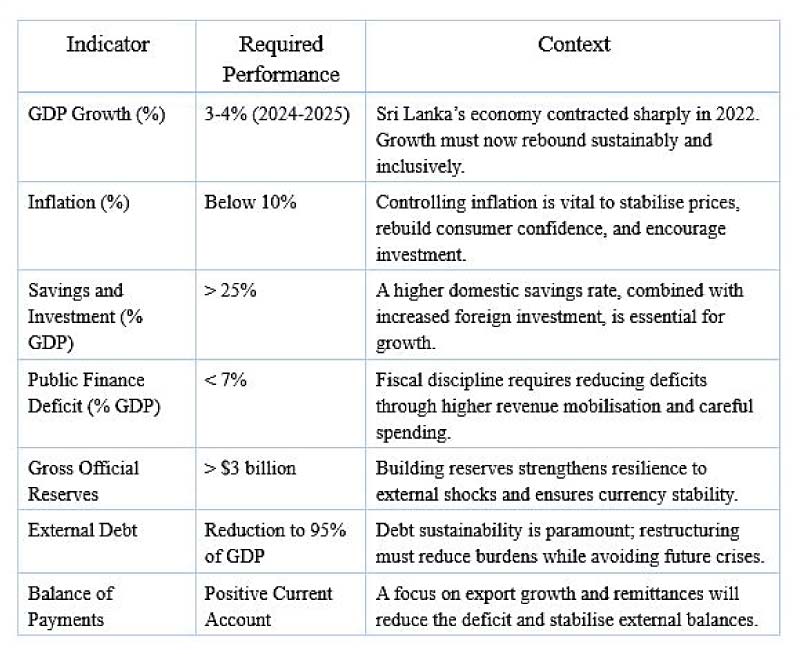

To understand the stakes, we must look at the key macroeconomic indicators that the IMF and the Government must address. These numbers are not abstract; they represent the very foundation of Sri Lanka’s recovery and long-term sustainability.

These targets are ambitious but achievable. However, the required performance up to 2028 will be particularly challenging given Sri Lanka’s recent economic trajectory.

Savings and investments: Pushing savings and investments beyond 25% of GDP will demand significant reforms to improve domestic savings rates and attract foreign direct investment (FDI). Sri Lanka’s savings rates have historically lagged behind regional peers, while political and economic uncertainty has deterred investors. A robust investment climate—underpinned by policy consistency, infrastructure development, and incentives for key sectors—will be crucial to meeting this goal. Without substantial improvements in capital inflows, particularly from exports and remittances, achieving this target will be arduous.

Public finance deficit: Reducing the fiscal deficit to below 7% of GDP requires bold measures to raise revenue and control spending. Sri Lanka’s revenue-to-GDP ratio remains among the lowest in the region, hampered by a narrow tax base and weak compliance. Achieving fiscal discipline will require comprehensive tax reforms, including widening the tax net, eliminating loopholes, and ensuring fairness in the system. On the spending side, there must be a careful balancing act—maintaining critical public services and social protection while cutting inefficiencies and wasteful expenditures. If these reforms falter, Sri Lanka risks falling back into unsustainable borrowing.

External debt: Bringing external debt down to 95% of GDP by 2028 will demand sustained progress on debt restructuring. Sri Lanka’s unsustainable debt load has been a key driver of its economic crisis, and the IMF’s support depends on meaningful reforms to improve debt transparency and management. Successful restructuring will hinge on negotiations with international creditors, as well as prudent new borrowing policies. Any misstep in these negotiations or further accumulation of high-interest loans would derail the debt sustainability targets.

Balance of payments: Achieving a positive current account balance will be no easy feat. Sri Lanka’s balance of payments has been strained by a combination of import dependency, weak export performance, and declining remittances. To reverse this trend, the country must focus on export diversification, strengthening its industrial base, and promoting sectors such as tourism and IT services. Import substitution policies may help in the short term, but long-term stability requires a strong export-driven economy. Without structural reforms to improve trade competitiveness, the current account targets could prove elusive.

Reserves, which plummeted dangerously low during the height of the crisis, must be rebuilt to over $ 3 billion. This will provide the country with a much-needed buffer against external shocks—something Sri Lanka sorely lacked in recent years. Meanwhile, the restructuring of external debt, currently unsustainable at over 100% of GDP, must bring it down to a manageable level. Failure on any of these fronts would risk derailing progress.

Lessons from the past: IMF programs and their pitfalls

Sri Lanka is not the first country to turn to the IMF during a crisis, and the global experience with such programs offers valuable lessons.

Take Argentina, for instance. Repeated IMF interventions failed to stabilise its economy, largely due to inflation spiralling out of control and political instability undermining reforms. Sri Lanka must avoid this trap by maintaining a clear focus on controlling inflation and fostering bipartisan support for its economic agenda.

Greece’s experience during the Eurozone debt crisis provides another cautionary tale. While IMF-backed austerity measures restored fiscal order, they came at a severe cost: deep economic contraction, social unrest, and a collapse in public services. Sri Lanka must learn from this and strike a balance. Fiscal consolidation is necessary, but it cannot come at the expense of social protection and economic growth.

Pakistan offers a different lesson—a cycle of IMF bailouts without meaningful structural reforms. Overreliance on external financing without addressing the underlying causes of the crisis—weak institutions, low revenue mobilisation, and poor governance—left Pakistan vulnerable to repeated economic shocks. Sri Lanka must break this cycle by committing to genuine, long-term reforms.

The common thread in these examples is clear: success hinges on consistent implementation, political stability, and a willingness to prioritise long-term gains over short-term fixes.

A vision beyond the immediate term

The Government’s focus must go beyond the immediate needs of stabilising the economy. While achieving the IMF targets is critical, Sri Lanka must also lay the groundwork for sustained, inclusive growth that benefits all citizens. This requires a clear, comprehensive vision that extends beyond the current parliamentary term.

Revenue mobilisation: Sri Lanka must widen its tax base and improve compliance. Progressive taxation, combined with efforts to close loopholes, can generate the revenue needed to reduce deficits without burdening the poor.

Debt management: The IMF’s recommendation to establish a consolidated Debt Management Office within the Ministry of Finance is essential. A centralised framework will ensure greater transparency, efficiency, and accountability in managing public debt.

Exports and investment: Long-term stability requires a shift towards export-led growth. Policies that support export-oriented industries, coupled with efforts to attract foreign direct investment (FDI), can create jobs and boost productivity.

Social protection: Economic reforms must not leave the most vulnerable behind. Targeted social safety nets can help cushion the impact of higher taxes, inflation, and spending cuts on lower-income households.

These measures require political commitment and institutional capacity. Crucially, they must outlast political cycles. A failure to think beyond the next election would jeopardise Sri Lanka’s hard-won progress.

The risks ahead: Proceed with caution

While Sri Lanka’s IMF deal offers hope, the risks are real. Political instability could derail reforms, as vested interests resist change. Reform fatigue, too, is a genuine concern—if the public does not see tangible benefits soon, support for the program could waver. Globally, external shocks—rising interest rates, slowing trade, or geopolitical tensions—could further complicate the recovery.

The Government must proceed with caution. An IMF deal is not a panacea; it is a foundation on which Sri Lanka must build its recovery. Strong institutions, consistent policies, and effective communication will be critical in navigating these risks.

A call to action: Seize the moment

Sri Lanka’s economic crisis has been a painful wake-up call. The IMF deal marks the beginning, not the end, of its journey. The Government now has an opportunity to reshape the country’s economic future—to move beyond crisis management and build a more resilient, inclusive, and prosperous nation.

But this will not happen by default. It will require discipline, vision, and leadership. The path ahead is difficult, but the stakes are too high to falter. With sustained reforms, political commitment, and a clear roadmap, Sri Lanka can not only recover but emerge stronger. The challenge is great, but so is the opportunity—let us not let history repeat itself.

(The writer is a Professor of Marketing, University of Surrey, UK. He can be reached via email: [email protected].)