Sunday Feb 22, 2026

Sunday Feb 22, 2026

Thursday, 31 October 2024 00:02 - - {{hitsCtrl.values.hits}}

Sri Lanka’s debt crisis is a stark example of the destructive power of predatory lending

|

The apparent ‘good news’ delivered by former President Ranil Wickremesinghe and Sri Lanka’s International Sovereign Bonds (ISB) holders in violation of the country’s election laws in September, is now being enshrined as the official position of the new National People’s Power (NPP) administration. The new President assumed power assuring renegotiation of the corrupt and disastrous ISB agreement.

The apparent ‘good news’ delivered by former President Ranil Wickremesinghe and Sri Lanka’s International Sovereign Bonds (ISB) holders in violation of the country’s election laws in September, is now being enshrined as the official position of the new National People’s Power (NPP) administration. The new President assumed power assuring renegotiation of the corrupt and disastrous ISB agreement.

Despite his recent claim that renegotiation of the plan is possible with a significant parliamentary majority in upcoming elections, his insistence on public endorsement is a thinly veiled attempt to legitimise a deeply harmful agreement. Moreover, the creditors’ overt interference in the electoral process is a blatant attempt to coerce the next Government into honouring a deal disastrous for Sri Lankans.

The Ceylon Chamber of Commerce, acting as the creditors’ mouthpiece as its members own approximately $ 1.8 billion in Sri Lanka’s outstanding ISBs (CBSL, April 2024. Annual Economic Review 2023) purchased at significant discounts reaching 40% to 50% of face value during the COVID-19 outbreak issued an ultimatum to the newly elected President. The Chamber demanded immediate implementation of the agreement disclosed on 19 September on the eve of the Presidential elections – a ticking time bomb set for the economy and its people. The terms of the deal, which favour creditors and the developed capitalist core over national interests, will inevitably lead to increased hardship of the masses, economic instability and worsening of terms of trade in the long run. The aim of this discussion is therefore to show the depths of the impending disaster and how those who support it stand to gain at the expense of public wellbeing.

19 September agreement in a nutshell

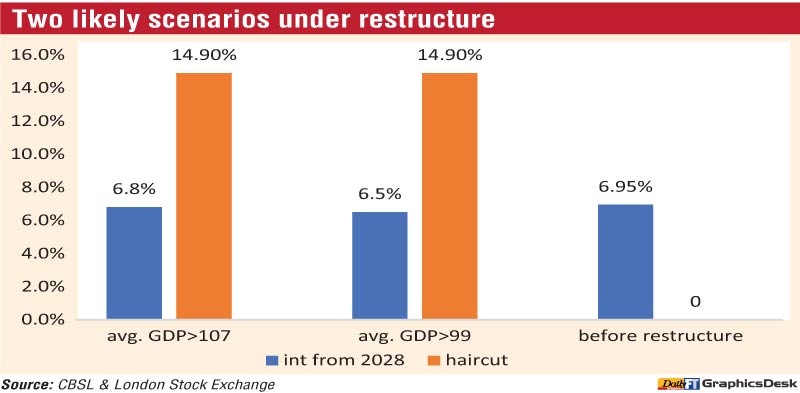

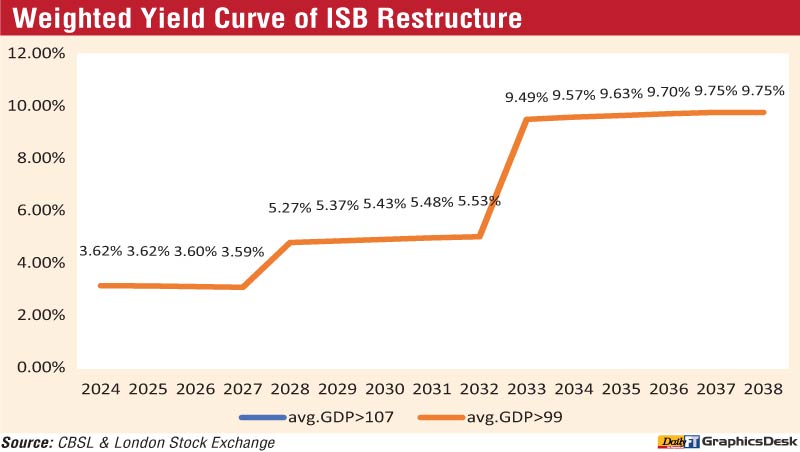

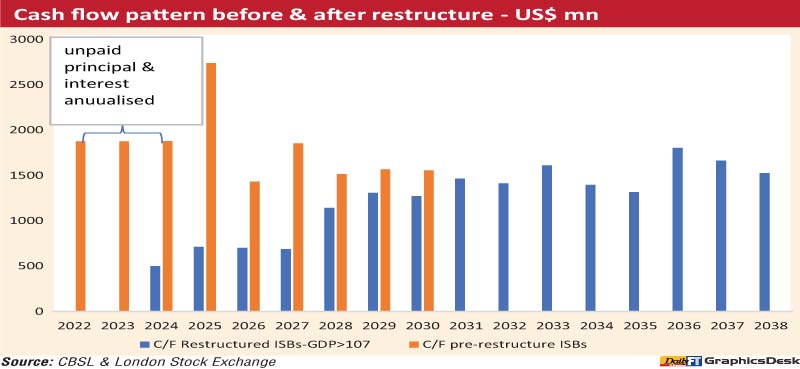

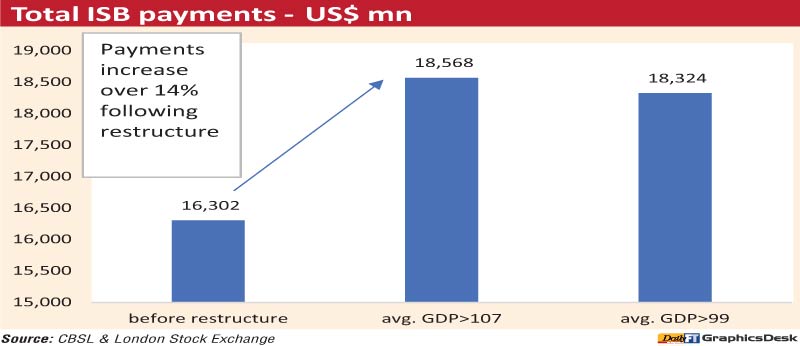

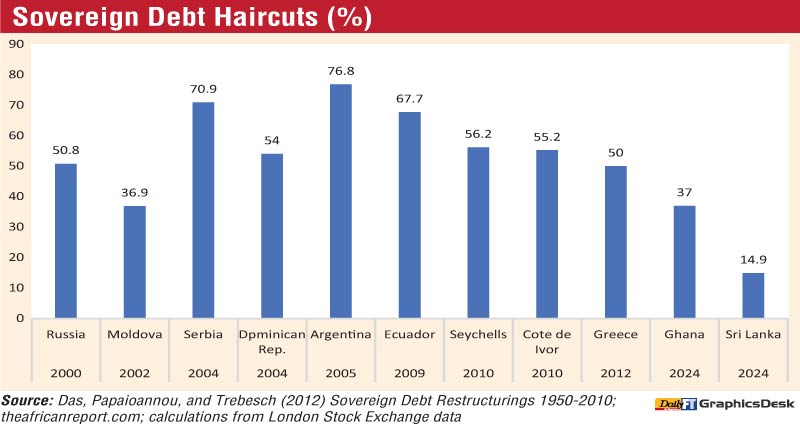

The proposed restructuring program extends the maturity period of ISBs from 2030 to 2038 under all scenarios expected for Sri Lanka’s nominal GDP. The extended maturity period masks a significant increase in total interest payments. In the first scenario, if the average nominal GDP between 2025 to 2027 exceeds $ 107 billion total nominal ISB payments will surge by over 14% to $ 18.56 billion from $ 16.3 billion before restructuring, amounting to an additional $ 2.3 billion in debt repayments over eight years. Under this arrangement, the weighted coupon rate of interest will be 6.8% from 2028 onwards while the average coupon rate will climb to 9.65% from 2032 onwards from 6.95% before restructuring. However, it is indicated that under this arrangement 14.9% haircut is offered on total principal payments. It should be evident that due to higher interest rates following 2028, the haircut grows back with fury after a little over two years of interest payments. This is indicated by total payments exceeding the initial payments by over 14% following the restructuring. Despite a nominal haircut, the higher interest rates will effectively erase any relief, leading to a net increase in debt servicing costs.

In the second probable scenario where Sri Lanka’s average GDP between 2025 to 2027 equals or exceeds $ 99 billion, the terms of debt repayment essentially remain the same as before except for an insignificant reduction of the weighted coupon interest rate from 6.8% to 6.5%. This will result in total payments reaching $ 18.32 billion, a negligible reduction of nearly $ 240 million over eight years for a reduction of nominal GDP by $ 8 billion compared to the $ 107 billion parameter of scenario one. Consequently, the total payments will exceed initial ISB payments by over $ 2 billion under scenario two.

It is outrageous that a restructuring program aimed at stabilising a country with a quarter of the population living in poverty (World Bank, April 2023, Poverty & Equity Brief) the weighted interest rate after restructuring is set to significantly exceed the expected real GDP growth rate. This is a violation of the ‘Golden Rule’ in economics derived initially by the works of Von Neumann and recently by the French Economist Thomas Piketty, where a real growth rate below the real interest rate will exponentially increase the degree of maldistribution of income in favour of capital compromising economic stability more and more as the gap between the two rates widens.

This is shockingly evident in the new ISB agreement. Under its terms if Sri Lanka’s real GDP growth exceeds 2.7% from 2024 to 2027 or cumulative real growth exceeds 11.5% during the period the weighted coupon rate of interest climbs to 6.8% and following 2032 the rates surge up to 9.75% for the next six years. This is more than twice the expected minimum real growth rate threshold stipulated in the agreement. By accepting these terms, Sri Lanka risks locking itself into a perpetual cycle of debt and underdevelopment.

The illusion of debt relief: The flawed NPV analysis

The use of Net Present Value (NPV) analysis to assess the impact of foreign debt restructurings, as employed by certain think tanks, is fundamentally flawed. This method is ill-suited for evaluating the complex dynamics of sovereign debt, particularly for third-world nations like Sri Lanka.

A core assumption of NPV analysis is that the value of the unit of account remains constant over time. However, this assumption is violated in the case of third-world countries, where currencies are prone to depreciation. As the Sri Lankan Rupee depreciates, the rupee cost of future debt payments, denominated in US dollars, increases significantly, which has to be met with increased taxation. This means that the burden on the nation’s economy, measured in local currency terms, grows exponentially. Discounting cash flows in NPV analysis can nevertheless show a reduction in payments due to restructuring. However, in reality, the rupee cost of the debt is rising exponentially with depreciation hand in hand with the higher value of nominal payments in US$ terms as discussed above in the case of Sri Lanka. Hence, from the perspective of the debtor nation, it is incorrect to use the NPV method and it is advantageous to the creditors at the expense of the former.

Furthermore, the NPV method is unsuitable for comparing debt portfolios with different maturity profiles. In the case of Sri Lanka’s ISB restructuring, the maturity period has been extended, altering the timing of cash flows. To accurately assess the impact of such changes, more sophisticated techniques like the Replacement Chain Method or Equivalent Annual Annuity Method must be employed.

By relying on the NPV method, analysts and policymakers risk underestimating the true cost of debt restructuring. This flawed approach can lead to misguided decisions that further exacerbate the nation’s financial woes. It is imperative to adopt a more rigorous and realistic framework for evaluating debt sustainability and the efficacy of restructuring efforts.

IMF distorts international norms to enforce indebtedness

The basis for this disastrous debt deal was laid by the IMF’s debt sustainability analysis (DSA). The DSA, a supposed exemplar of neutrality and impartiality, is weaponised to lock the nation into a cycle of indebtedness. The IMF declared that Sri Lanka’s debt-to-GDP ratio must decline to 95% by 2032 from nearly 113% in 2023 to reach sustainability. This envisaged debt ratio of 95% is almost twice that of the ratio declared by the World Bank in the 1990s which would classify a low-income economy as highly indebted. This was reiterated by the United Nations in 2006/07 declaring that a developing economy with a nonconvertible currency is highly indebted if its total outstanding debt to gross national income exceeds 50% (see Nihal Kappagoda, 2007, Debt Sustainability Framework for Low-Income Countries, United Nations).

This indicates that the ratio assigned for Sri Lanka by the IMF is designed to sustain the indebtedness of the economy and its people as opposed to reaching debt sustainability. More importantly, this manipulation by the IMF cripples Sri Lanka’s bargaining power with creditors. The nation is forced to accept meagre reductions in principal payments, ensuring a steady flow of wealth from Sri Lanka to lenders.

Furthermore, the IMF-World Bank debt sustainability framework first launched in April 2005 and periodically updated holds that if the threshold for debt sustainability shown by the present value of total outstanding debt being greater than or equal to 70% of the GDP a country has higher capacity for debt repayment (see https://www.imf.org/en/About/Factsheets/Sheets/2023/imf-world-bank-debt-sustainability-framework-for-low-income-countries). Present value of outstanding debt implies that we consider the total discounted future interest payments of borrowings in addition to outstanding principal amount borrowed as a ratio of the GDP.

Therefore 95% debt to GDP ratio assigned for Sri Lanka which also excludes the present value of interest payments indicates that Sri Lanka’s capacity to repay is greater than the strongest economies as per IMF standards! This is invariably an outrageous distortion and a vicious manipulation of accepted parameters to enrich creditors at the expense of an impoverished population. This manipulation by the IMF demolished the bargaining power of Sri Lanka to demand a meaningful reduction on principal payments of foreign debt at negotiations with creditors.

In turn it not only allows the extraction of surpluses in the form of debt repayments: the unbearable debt repayments will continue to weaken the currency in the long run. It ensures that the product of labour is extracted at the lowest possible price in the form of exports. This underlying aim is further emphasised by the IMF demanding labour market liberalisation as a binding condition to approve its ongoing program, exploiting the vulnerable position of the economy to its fullest. The new labour laws seek to abolish the eight-hour working day by changing the threshold to a 40-hour work week which will also abolish the need to pay overtime for work performed more than eight hours a day. Hence, the debt crisis is exploited to further suppress the terms of exchange between the developed capitalist core and an underdeveloped economy. It will also deny the nondebt form of capital required to transform the economy from its underdeveloped third-world status.

Government colluding with creditors

The agreement also demands that the creditors hold the right to alter the current governing law of Sri Lanka’s outstanding ISBs from New York to UK or Delaware law. As we have reiterated in our earlier accounts (https://www.ft.lk/columns/DDR-wipes-out-half-of-EPF-ETF-incomes--An-act-of-financial-terrorism-by-CBSL/4-753829) the US law allows countries to declare debt cancellations if it can establish that borrowed funds were not used in the best interest of the public and have enriched a few under previous governments or have been the means to suppress human rights, the knowledge of which cannot be denied by the creditors (see Buchheit, L. C., Gulati, M. & Thompson, R. B. 2007. The Dilemma of Odious Debts, Duke Law Journal).

The majority of Sri Lanka’s external debt can be categorised under this framing. Therefore, by agreeing to uphold the new agreement Sri Lanka has effectively waived the legal right for securing a higher debt cancellation. This is the ‘good news’ delivered by the former President and now embraced by the new NPP administration.

Sri Lanka’s Government entertaining the interests of the creditors at the expense of the general public is further revealed by the recent experience of Ghana’s debt restructuring. The government of Ghana rejected a disastrous proposal similar to that of Sri Lanka made by its international creditors. It reached an agreement with 90% of bondholders meaningfully reducing both principal and interest payments. Ghana secured a 37% haircut on outstanding sovereign debt while the maximum interest rate applicable for new bonds was capped at 6% as opposed to 9.75% for Sri Lanka. As a result, its nominal debt relief amounts to $ 4.4 billion (see https://www.theafricareport.com/363637/ghana-bondholders-take-37-haircut-in-debt-restructuring-deal/) as opposed to increase in nominal payments of Sri Lanka by up to $ 2.3 billion.

In contrast, the proposal submitted through its advisors, Lazzard and Clifford & Chance, in April 2024, Sri Lanka demanded an equally disastrous deal comparable to that of creditors’ where interest rates reach a maximum of 9.5% for a debt that was borrowed at 6.95%. Ironically, bilateral lenders and the IMF disagreed with the initial agreement stating that it violates comparability of treatment and does not meet IMF program requirements. Furthermore, Lazzard was the financial advisor for both Ghana and Sri Lanka in the process. Sri Lanka demanding a program benefiting the creditors and both countries hiring the same financial advisor points to the conclusion that the Government of Sri Lanka was directly colluding with the creditors and the deal was mired in corruption.

The current NPP administration has agreed to implement a new variant of the same corrupt deal which merely reduces the weighted coupon rate of interest of bonds from 8.1% to 6.5% from 2028 onwards reducing total payments by $ 1 billion. The new Government must reject this destructive path and prioritise people’s interests.

It is evident that the Sri Lankan Government’s actions have been influenced by corrupt interests. The cosy relationship between the Government and international creditors raises serious questions about transparency and accountability. The new administration must break free from this destructive path and prioritise the well-being of the Sri Lankan people.

The role of predatory lending

Sri Lanka’s debt crisis is a stark example of the destructive power of predatory lending. Despite the nation surpassing the critical 50% debt-to-GDP threshold, international lenders continued to pile on debt, disregarding basic financial prudence. Commercial banks typically adhere to a 1:1 debt-to-income ratio, carefully assessing a borrower’s creditworthiness to mitigate default risk. For instance, commercial banks assess whether the borrower has already piled up a mountain of debt that is unpayable before lending further. However, when lending to Sri Lanka and the rest of the third world, the metropolitan lenders wilfully violated these accepted criteria, which are in place to mitigate risks of default.

Sri Lanka’s lenders have continued to sink the economy in a bottomless ocean of debt; they persisted in extending credit even as government revenue hovered around a mere 10% of GDP and debt-to-GDP ratios approached 100%. This reckless behaviour, where debt exceeded government revenue by a factor of ten, is a clear indication of predatory lending practices. Established norms in lending were blatantly violated by creditors to Sri Lanka and other third world nations. It is imperative to hold these lenders accountable for their role in exacerbating the debt crisis in the third-world. By ignoring sound financial principles and fuelling unsustainable debt burdens, they have contributed to the economic hardship faced by millions of poor across the global South.

(The writer is attached to the Institute of Political Economy.)