Thursday Feb 19, 2026

Thursday Feb 19, 2026

Wednesday, 14 August 2019 00:00 - - {{hitsCtrl.values.hits}}

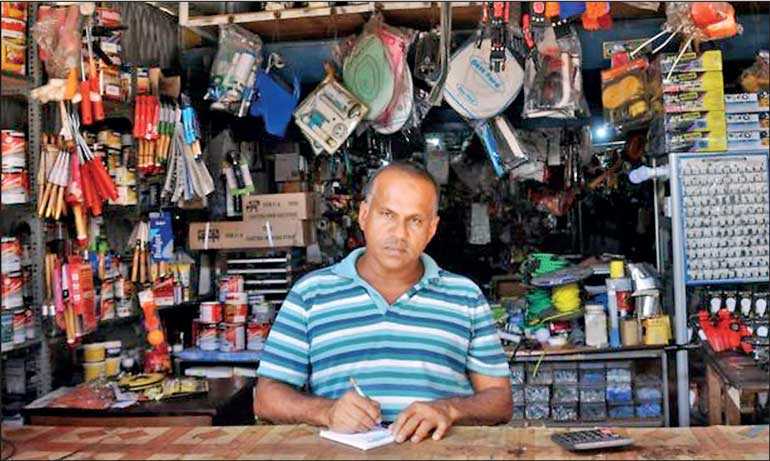

BBC: Until a few months ago, Mohammed Iliyas, was doing a thriving business in his hardware shop in western Sri Lanka. Now trade has plummeted and his losses are mounting.

His shop stocks everything from paint tins to electric bulbs and is one of the better known in and around Kottaramulla village, about 90 kilometres (56 miles) from the capital Colombo.

|

Buddhist monk Galagoda Aththe Gnanasara Thero has been accused

|

Minority Muslims live among the majority Sinhalese community in this area. For decades, Iliyas, who is a Muslim, spent his days serving people from all religious communities.

But that has changed since Sri Lanka’s Easter Sunday bombings in April.

“Since the Easter Sunday bombings, almost 90% of my Sinhalese customers have stopped buying from my shop. My business has gone down significantly and I have lost hundreds of thousands of rupees,” Iliyas said.

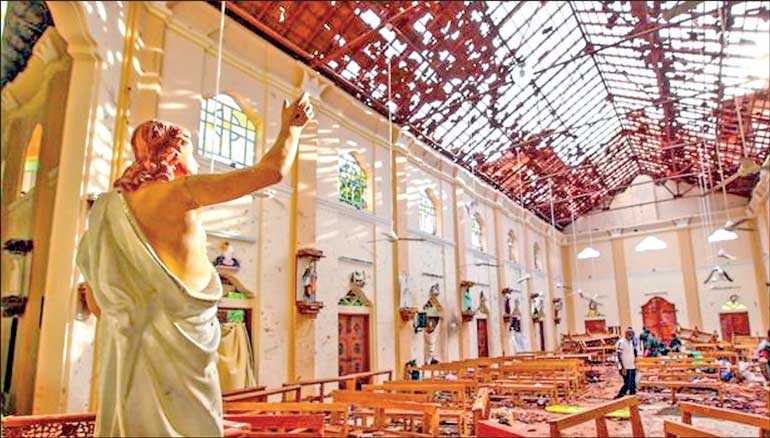

Islamists linked to little-known local groups targeted high-end hotels and churches in Colombo and in the east of the country killing more than 250 people, including foreigners. The devastating attack, claimed by the Islamic State group, shocked the nation.

“Though some customers have started coming back in recent weeks it is not enough. If this trend continues then I am in big trouble,” Iliyas said.

Many Muslims feel that since the suicide bombings they have been demonised, and traders from the community say that they have become a target.

There have been attacks on Muslim-owned businesses and houses in several parts of Sri Lanka, with the worst violence in May.

In June, a senior Buddhist monk openly called on the Sinhalese people not to buy from Muslim shops, prompting strong criticism from Finance Minister Mangala Samaraweera, who urged ‘true Buddhists’ to unite against what he described as the ‘Talibanisation’ of the religion.

Ethnic and religious fault lines run deep in a multi-ethnic and multi-religious Sri Lanka. Muslims make up nearly 10% of Sri Lanka’s 22 million people, who are predominantly Sinhalese Buddhists.

About 12% of the population are Hindus, mostly from the ethnic Tamil minority, and 7% are Christians.

The country endured a brutal civil war that ended in 2009 with the total defeat of the separatist Tamil Tiger rebels. Tens of thousands of people were killed in the nearly three decade-long conflict. Nearly 10 years of relative peace was shattered on Easter Sunday.

Muslims across the island have denounced the senseless killings. But their outright rejection of violence and condemnation hasn’t satisfied a section of Sinhalese hardliners. Initially, their anger was directed at those that follow the hard-line Wahhabi form of Islam.

Now Muslim leaders say that the entire community is facing retaliation. They feel that Sri Lanka’s mainstream politicians and the security forces are indifferent to violence against them. The government says it has increased security to control communal tensions.

“My brother was killed just outside the house by a Sinhalese mob who were vandalising Muslim properties in June this year. We are not sure whether we will get justice,” said Mohamed Najeem, who lives in north-western Sri Lanka’s Puttalam district.

Police say that two people have been arrested in connection with the killing of Najeem’s brother, Mohamed Ameer Mohamed Sally, and investigations continue.

Muslim women wearing traditional Islamic dress were also targeted after Easter Sunday as the government banned face coverings in public, citing security reasons.

Though the niqab and burka – which cover most or all of the face and are worn by some Muslim women – were not specifically named, rights groups say even those wearing head scarves have been harassed.

“Muslim women working in government offices are facing problems. In some places, those who are wearing only headscarves are being asked to go home and come back wearing a saree,” said Juwairiya Mohideen, director of the Muslim Women Development Trust.

Some Sinhalese women refuse to sit next to Muslim women wearing the traditional Abaya – a long loose-fitting robe – on public buses, she said.

Community representatives say actions including boycotts of Muslim businesses are in part driven by the messages of local Buddhist clergy, who are in turn inspired by senior monks.

One monk accused of triggering anti-Muslim sentiments in the past is Galagoda Aththe Gnanasara Thero, leader of the Bodu Bala Sena (BBS) or ‘Buddhist Power Force’, a nationalist group.

“No organisation has asked people not to buy from Muslim shops. People are doing it on their own, we have nothing to do with it,” he said.

President Maithripala Sirisena pardoned the monk in May this year, freeing him from prison after he had served less than a year of a six-year prison term for contempt of court.

“The Muslim community will have to discuss among themselves and find answers. We don’t say that all the Muslims are involved in violence. But Muslim businessmen should find out those who are supporting hardline Islam and expose them,” the BBS leader said.

But Muslim leaders said the monk should question his own views. “He must stop pontificating to us. He must turn the search light inwards,” said Rauff Hakeem, the leader of the Sri Lanka Muslim Congress and a minister in the government.

He said Muslims were willing to engage in serious introspection to find out where things went wrong in the community and they were already doing so voluntarily.

“When hate speech emanates from totally unexpected quarters at the high echelons of religious power it is very disappointing and quite disgraceful,” said Hakeem.

There have been some signs of progress for Sri Lanka’s Muslims in recent weeks.

Muslim ministers who resigned in May this year to protest the linking of their entire community with terrorism have been sworn in again as ministers.

A Muslim gynaecologist who was accused of sterilising thousands of Buddhist women against their will has been released on bail.

Dr. Mohammed Shafi was taken into custody in May after a Sinhala newspaper published a report making the allegations without any evidence. He was held for several weeks despite the Criminal Investigation Department informing the court that there was no evidence against him.

Some Muslim traders in Colombo’s busy Pettah market also said their Sinhalese customers had started coming back, though at a slow pace.

But they were anxious to see how the situation would develop as the country gears up for a presidential election that has to be held by 9 December. National security is expected to be a key political issue.

Muslim leaders fear that anti-Muslim rhetoric will be used for political point-scoring, and to divide communities.

“They should realise this kind of polarisation and demonisation of a community can (actually) create a fertile ground for further radicalisation,” warned Hakeem.

Sri Lankan Muslims hope and pray that they will not become a pawn in a bigger political game. (Source: https://www.bbc.com/news/world-asia-49249146)