Saturday Feb 21, 2026

Saturday Feb 21, 2026

Friday, 21 October 2022 00:00 - - {{hitsCtrl.values.hits}}

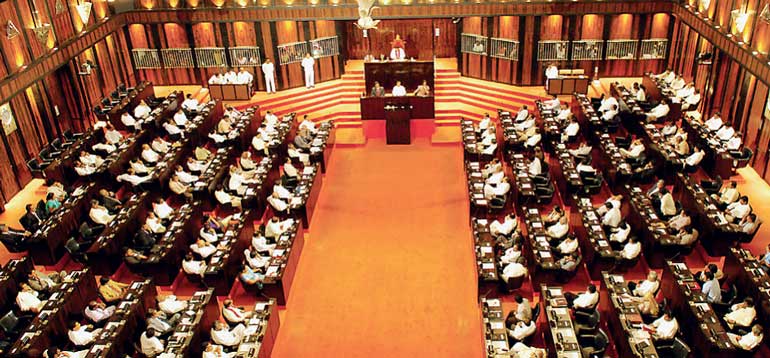

The Sri Lankan Government should withdraw a draft law that would give the authorities broad powers to detain people in military-run ‘rehabilitation’ centres, placing them at great risk of abuse, Human Rights Watch said this week.

The Bureau of Rehabilitation Bill, submitted to Parliament on 23 September 2022, would allow the compulsory detention in centres of “drug dependant persons, ex-combatants, members of violent extremist groups and any other group of persons.”

The Bureau of Rehabilitation Bill would establish a new administrative structure controlled by the Defence Ministry to operate ‘rehabilitation’ centres staffed by military personnel. The proposed law, which human rights advocates have already challenged in the Supreme Court, does not describe the basis for being sent for ‘rehabilitation,’ but other recent Government policies provide vague and arbitrary powers to forcibly ‘rehabilitate’ people who have not been convicted of any crime.

“The Sri Lankan Government’s proposed ‘rehabilitation’ efforts appear to be nothing more than a new form of abusive detention without charge,” said Meenakshi Ganguly, South Asia Director at Human Rights Watch. “The Rehabilitation Bill would open the door widely to more torture, mistreatment, and endless detention.”

The Sri Lankan Government has previously used coercive ‘rehabilitation’ centres to enable arbitrary detention and torture. Following the civil war, which ended in 2009, thousands of people whom the Government identified as members of the defeated separatist Liberation Tigers of Tamil Eelam were detained in military-run ‘rehabilitation’ centres, where some were allegedly tortured and subjected to other abuses, including sexual violence. The current bill seeks once again to ‘rehabilitate’ ‘ex-combatants’ 13 years after the war ended.

The Rehabilitation Bill is the latest measure in a long history of laws, such as the Prevention of Terrorism Act (PTA), that authorise arbitrary detention and torture in Sri Lanka. The law could be used to target minority communities or anti-Government protesters whom President Ranil Wickremesinghe has labelled “extremists.”

Under the Rehabilitation Bill, which would allow prolonged detention without judicial oversight, Government officials would be protected from criminal liability for their actions if they act “in good faith.” The bill also empowers officials to use undefined “minimum force” to “compel obedience” from detainees. Another provision provides that an official who “without reasonable cause” strikes, wounds, ill-treats, or wilfully neglects anyone under rehabilitation can be punished by up to 18 months in prison, suggesting that there might be a “reasonable cause” to harm detainees. International law absolutely prohibits torture, and other cruel, inhuman or degrading treatment or punishment.

A separate bill to amend Sri Lanka’s Poisons, Opium and Dangerous Drugs Ordinance, which was presented to Parliament on 9 September, provides for the compulsory rehabilitation of alleged drug users. The legislation would worsen already abusive laws and practices under Sri Lanka’s “war on drugs,” which Sri Lankan military officers have repeatedly compared to the “war on terror.”

Sri Lanka already has a system of forced “rehabilitation” for alleged drug users, which is run by the armed forces at two sites previously used to “rehabilitate” former combatants. There have been allegations of forced labour and ill-treatment, including the collective punishment of inmates, who are denied access to medically appropriate treatment for drug dependency while undergoing coercive “de-addiction.” The death of an inmate at the Kandakadu rehabilitation centre in June led to the arrest of four army and air force sergeants acting as “therapists.”

International standards for the treatment of addiction maintain that treatment should always be voluntary and addiction regarded primarily as a health condition. The abstinence-based “rehabilitation” programs operated by the military are not based on scientific evidence and provide no harm reduction services.

In 2017, the United Nations Working Group on Arbitrary Detention expressed concern at the involvement of the Sri Lankan military in drug treatment and at the lack of medical care, as well as irregularities in the judicial process. The detention of alleged drug users for coercive “rehabilitation” is incompatible with medically appropriate drug dependency treatment and contravenes international law, Human Rights Watch said.

The proposed amendment to the drug law contains provisions to weaken evidentiary standards and deny bail to suspects in some criminal cases related to the possession of drugs. Sri Lanka continues to impose the death penalty for some drug offenses, contrary to international law standards and despite a national moratorium on executions since 1976.

The Rehabilitation Bureau Bill and the proposed amendment to anti-narcotics legislation are only the latest measures in President Wickremesinghe’s assault on fundamental rights, Human Rights Watch said. An attempt to use the Official Secrets Act to restrict public gatherings in the capital, Colombo, was withdrawn earlier in October amid widespread objections that the action was unlawful.

On 6 October, the United Nations Human Rights Council adopted a resolution expressing concern at the human rights situation in Sri Lanka and mandating enhanced UN monitoring, as well as renewing a mandate for the UN to collect and analyse evidence of past human rights violations for use in future prosecutions.

“President Wickre-mesinghe is pursuing abusive and repressive policies that make it difficult for Sri Lanka’s international partners to wholeheartedly back desperately needed economic measures,” Ganguly said. “Foreign governments should make clear that they will support the urgent needs of the Sri Lankan people, but they will also take action through targeted sanctions and other measures against those committing serious human rights violations.”