Sunday Feb 22, 2026

Sunday Feb 22, 2026

Thursday, 9 January 2025 01:48 - - {{hitsCtrl.values.hits}}

By Ranmalee Nanayakkara

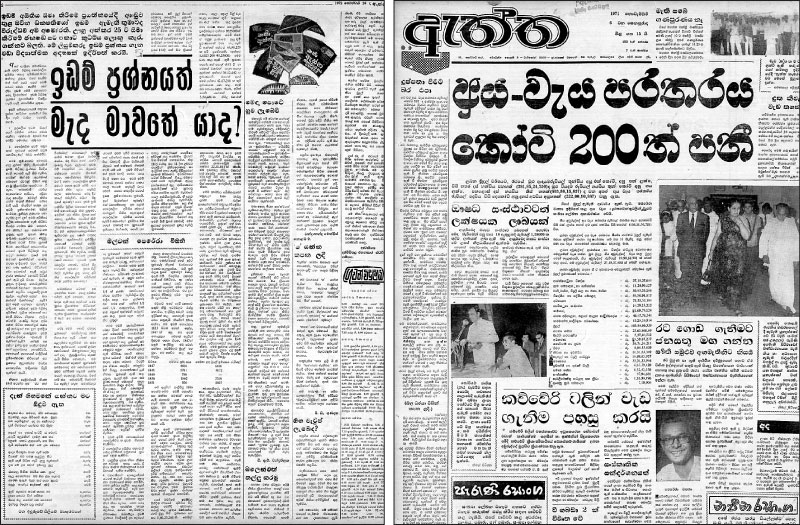

In the early 1970s, Sri Lanka found itself grappling with multiple internal and external economic factors that would culminate in an economic crisis during the Sirimavo Bandaranaike Government. Back then, daily newspapers were the main source of information available to the public, and notable among these was the Aththa (Truth) newspaper, a Sinhala-language daily published by the Communist Party of Sri Lanka (CPSL).

Sirimavo’s United Front (UF) alliance won an overwhelming majority in the 1970 General Election, defeating Dudley Senanayaka’s United National Party (UNP). The UF had ministers from several leftist parties including the CPSL. Pieter Keuneman and B.Y. Tudawe both held ministerial positions in the coalition Government.

In the early days of the coalition, the Aththa newspaper adopted a largely pro-UF stance, promoting the Government in various ways. The following is taken from an Aththa article published just before the 1970 General Election (1970/05/26). This particular issue also carried an advertisement issued by a group of UF supporters urging readers to be aware of news spread by capitalist newspapers.

“Sirimavo Bandaranaike requires no introduction, as her dedicated service to the nation speaks volumes. She is revered as a maternal figure for her profound impact on our country” - Malwatu Maha Nayaka

“Our struggle extends beyond merely ousting the Government led by Dudley Senanayaka; it also aims to establish a Government comprising the Lanka Sama Samaja – Communist coalition within the United Front. All three parties have wholeheartedly embraced this vision, and our policies are unequivocally aligned with it”.

However, severe inflation between 1973 and 1974 sparked economic uncertainty in the country and public dissatisfaction against the government grew. The Aththa newspaper began to criticise the UF coalition and its policies. The following is taken from the Aththa editorial published on 25 May 1972.

“The true measure of Government ministers lies not in their rhetoric but in their ability to actualise their proposed visions through implementation”

As public discontent grew, Aththa began to criticise the same Government it had backed, revealing how whenever there was political turmoil in the country the Aththa would side with the people.

The newspaper was critical of capitalist policies, often highlighting socio-economic disparities and injustices within Sri Lankan society. After the UF Government came into power, it embarked on an ambitious economic agenda aimed at shifting the country from a liberal market structure toward a state-led model.

Between 1968 and 1970, Sri Lanka began modest economic liberalisation, easing trade restrictions, promoting private investment in select industries, and boosting agricultural exports. However, from 1970 to 1977, this trend reversed as the Government pursued a socialist agenda, bringing trade, industry, agriculture, and banking under State control. State-owned enterprises expanded significantly, emphasising centralised economic planning.

In a system where getting permission to import was difficult, and what you imported determined how well your business did, Government officials wielded significant power. By the mid-1970s, Sri Lanka’s economic trajectory veered sharply inward, with strict Government rules on trade and cash flow. It was like sailing into unknown waters on the world’s economic map.

As indicated in the Ceylon Today, 2018:

“This started off when the Sri Lankan Government implemented significant land reforms driven by socialist principles, resulting in the nationalisation of approximately 502 privately-owned tea, rubber, and coconut estates. This move aimed to curtail the extent of privately-held land holdings”

Sirimavo’s administration initiated land reforms to tackle landlessness and enhance agricultural output. The 1972 Land Reform Law sought to redistribute land to those without it, empowering rural dwellers and promoting agricultural self-reliance.

An Aththa article by Milton Perera on 26 February 1972 notes:

“The Government’s imperative now lies in reclaiming lands rightfully belonging to foreigners without compensation. This approach stands as both just and effective. Centuries of exploitation by foreign companies, predominantly of white descent, have exploited our people and resources. It’s time to rectify this historical injustice”.

Throughout this period, the Government invested extensively and prioritised substitutes, a trend that was highlighted by the Aththa in 1972:

“Only 25% of the country’s population constitutes the active labour force, with the remaining 75% relying on this minority for sustenance. This imbalance contributes to a stagnant economic system within the country”.

From 1972 to 1977, there were calls to the Government to halt the import of certain goods including machinery and equipment. In an Aththa interview on 18 January 1973, S.S.S. Karunathilaka, a former Additional Research Director at the Central Bank, mentioned the sole path to economic recovery lay in developing the country’s agricultural sector. He said the country should consider prohibiting the import of tractors and other such agricultural machinery, and instead focus on domestic production of these items to stimulate national economic growth.

These constant shifts in policies between the major political players posed a significant challenge to the Sri Lankan economy during this period. Reading the Aththa sheds light on the profound shifts in policy that had a dramatic impact on Sri Lanka’s economy. This pattern, sadly, resonates even in today’s context. Governments of the past, in their bid to please various stakeholders, often altered policies without considering long-term consequences. The recent 2022 economic crisis serves as a stark reminder of this phenomenon, mirroring the patterns seen during the economic turmoil of the 1970s.

In 2021, the Sri Lankan Government persisted with ill-conceived policies, including flawed monetary strategies, mounting foreign debt, stringent import regulations, and dwindling export revenues. These decisions stemmed from a short-sighted focus on appeasing voters rather than prioritising the country’s economic growth. Short-term fixes and fleeting satisfaction only sowed seeds of chaos, ultimately causing the president to step down. This underscores the importance of stable, enduring policies that foster long-term growth rather than serving the narrow interests of a few.

In tracing the economic journey of Sri Lanka through the 1970s, the Aththa newspaper provides a revealing lens into the shifting policies, ideological battles, and public responses that shaped the era. Initially a fervent supporter of the UF Government’s State-centred approach, Aththa later became a critical voice, capturing the people’s growing disillusionment with failed economic strategies that ultimately deepened day-to-day hardships.

This archive reminds us of the cyclical nature of economic policies shaped by political motivations that resonate with the recent economic challenges of 2022. As the country grapples with current issues of foreign debt, inflation, and policy instability, the lessons from the Aththa newspaper serve as both a historical record and a cautionary tale, underscoring the need for sustainable, well-considered economic strategies that prioritise the long-term welfare of the country and its citizens.

The Aththa newspaper from 1964-1992 is now digitised and open-access on JSTOR.

https://www.jstor.org/site/south-asia-open-archives/saoa/aththa-38065172/?so=item_title_str_asc