Monday Feb 16, 2026

Monday Feb 16, 2026

Wednesday, 17 April 2019 00:00 - - {{hitsCtrl.values.hits}}

By Natasha Fernando

Sri Lanka is an island nation in the Indian Ocean located at the tip of the South Asian Subcontinent. Often praised as the pearl of the Indian Ocean, it’s strategically located among important sea lanes of communication that passes through strategic chokepoints including Strait of Malacca, Bay of Bengal and Gulf of Mannar.

Sri Lanka is thus located close to important bodies of water, making the island geographically prominent but also geographically vulnerable due to several contentious issues: The Palk Strait conundrum, Sethusamudram Ship Canal Project, and climate change.

Sri Lanka’s geographic blessings

Historically the Strait of Mannar has been a short cut between the Far East and the Indian Ocean, posited in a manner important for intercontinental shipping.

The Bay of Bengal is becoming increasingly strategic owing to several facts: being the largest bay in the world, with important trade routes traversing through it, and being associated with the Bay of Bengal Initiative for Multi-Sectorial Technical and Economic Cooperation (BIMSTEC). Sri Lanka has the current chairmanship of the BIMSTEC which could be attributed to Sri Lanka’s geographic advantage being located at such close proximity to the Bay.

The Gulf of Mannar is not of a high economic importance but is very significant in terms of biodiversity with the richest concentrations of Marine Species. In fact the UNDP is engaged in a project to declare the Reserve as a protected zone. Being close to international shipping routes has garnered attention to Sri Lanka’s main ports, including Colombo, Trincomalee and Hambantota.

Ambassador Wharton visiting Sri Lanka for its 69th Independence Day ceremony stated: “Forty percent of all seaborne oil passes through the former and half the world’s merchant fleet capacity sails through the latter, making the sea lanes off of Sri Lanka’s southern coast some of the world’s most important economic arteries.”

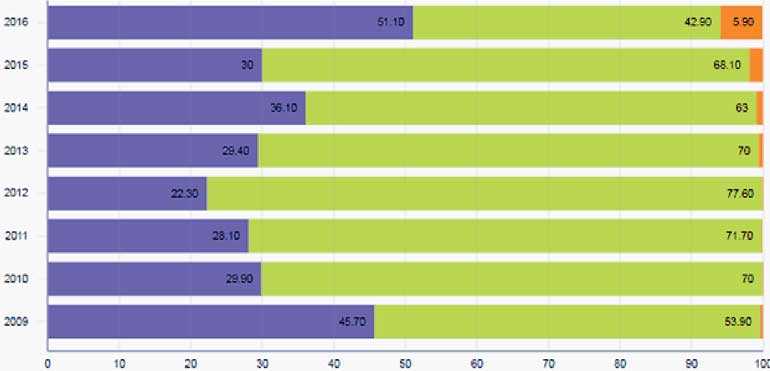

The Colombo Dockyard is generating massive income through ship repairs, ship building, and heavy engineering. The graphic demonstrates the percentage of revenue generation sector-wise. Purple represents ship repairs, green depicts ship building, and orange shows heavy engineering. Accordingly, ship repairs have increased since the drop in 2012. Ship building has remained at an average of 60% through 2009-2016. The percentage of heavy engineering services has increased. Interestingly, the Colombo Dockyard has embarked on ambitious projects including the recent launch of cable laying vessel designed for subsea operations, installation and repair works of optical and power cables. These projects have been possible due to Sri Lanka being utilised for refuelling, docking, and repair functions as an important transhipment hub in the Indian Subcontinent.

The geographic vulnerabilities

The Palk Strait separates India from Sri Lanka but no ship can pass through it as it lacks sufficient depth. According to GlobalSecurity.org, the real distance by sea between the Arabian Sea and the Bay of Bengal does not exceed 1,500 nautical miles. Without a shipping route through the Palk Strait, ships must navigate around the southern tip of Sri Lanka which is a longer route.

The Sethusamudram Ship Canal was proposed to cure this deficit. Although discussions were underway, and the Indian Government appointed the Sethusamudram Project Committee in 1955, the project was never realised. It was met with hostilities from environmental lobby groups which contested the feasibility of the project. The project was further stalled during the LTTE hostilities.

The negotiations during the ceasefire in 2003 between the Government of Sri Lanka, the LTTE and India were not successful as the LTTE claimed right to patrol the sea within certain demarcations. The Indian Government refused to recognise the authority of the LTTE since patrols may only be conducted by a legitimate government force. Allowing the LTTE this function would seem to endorse terrorism.

The geographical conundrum of the Sethusamudram is a sad trajectory. If we were to reiterate an old mythical tale of Rama and Seetha; when Rawana (the beastly magical king of Sri Lanka) abducted the beautiful Seetha, maybe the gods cursed the shoals, offshore islands and sediment areas of the Palk Strait.

The other assumption is a conspiracy theory, due to security concerns contingent on the development of the Sethusamudram, the Hambantota harbour was built down south. Therefore, there will arise ‘no need’ for the Sethusamudram. After all, Colin Chapman states: “The deep-sea port, constructed and largely financed by the Chinese at a cost of $ 1.5 billion, straddles a major eastward shipping route used by 200 to 300 international vessels daily.”

Finally, climate change presents a geographic dilemma for Sri Lanka which is an island state that is directly impacted by global warming and rising sea levels. The low-lying coastal lines will be subject to shoreline erosions damaging the coastal eco-systems and livelihoods.

Sri Lanka has suffered much during the severe flooding and severe droughts in various parts of the countries. These changing climate trends adversely impact the agricultural sector which amounts to 7.8% of GDP and occupies 28% of the labour force. What is our future? The geographical position of Sri Lanka is thus both a blessing and a curse providing opportunities and creating vulnerabilities.

In order to leverage Sri Lanka’s geographical advantages, the policy makers must open the country’s economy to facilitate international shipping trade which in future will be a main source of income to the nation. This includes developing the capacities and promoting the Hambantota Port for re-fuelling, docking and repairing services. The logistical lines between Colombo and Hambantota must be strengthened.

Further, Sri Lanka’s Coastguard and Navy as the country’s first line of defence must factor climate change assessments into their maritime security strategy. There should be timely humanitarian assistance and rescue rendered to those affected by natural disasters.

Only consistent policies on risk reduction and disaster mitigation practices in the agricultural sector will make livelihoods resilient in the face of climate change. The relevant experts must be consulted on these pressing issues to face the uncertainties of the future.

(Natasha Fernando is an independent researcher. She is a graduate of University of Kelaniya and University of London, specialising in international studies and law.)

(Source: http://southasiajournal.net/sri-lankas-geographic-conundrum-lessons-for-the-future%ef%bb%bf/)