Wednesday Feb 18, 2026

Wednesday Feb 18, 2026

Friday, 6 May 2022 00:00 - - {{hitsCtrl.values.hits}}

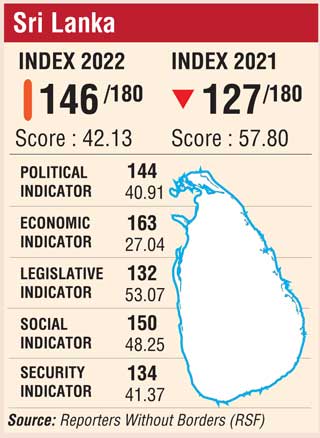

Sri Lanka has slipped in the latest media freedom index compiled by the Reporters without Borders (RSF).

Sri Lanka was ranked at 146 out of 180 countries in the 2022 index with a score of 42.13 as against 127th position in the 2021 index with a score of 57.80.

RSF said press freedom issues are closely tied to the civil war that ravaged the island until 2009, and to the crimes – still left unpunished – against many journalists during the crushing of the Tamil rebellion. With a media sector lacking diversity and highly dependent on major political clans, journalism is at risk.

Media landscape

State-owned media dominate the sector. The Ministry of Mass Media runs, among other outlets, the Sri Lanka Broadcasting Corporation (SLBC), the Rupavahini Corporation (SLRC), the Independent Television Network (ITN) and Associated Newspapers of Ceylon Ltd. (ANCL), whose editorial staff – be they print, radio, TV and internet – lack almost all independence. Journalists in the private sector are in essentially the same situation, as most owners of major media have clear political affiliations. In the print media, the four biggest owners share three-quarters of the country’s readership. The main press group, Lake House, belongs to the Wijewardene family, which alone owns more than half of the country’s publications. An RSF study concluded that fewer than one in five Sri Lankan citizens have access to politically independent media.

Political context

President Gotabaya Rajapaksa made a name for himself as secretary to the Ministry of Defence in the government of his brother, Mahinda, between 2005 and 2015. During that period, which Sri Lankan journalists describe as a dark decade, “Gota” became notorious as chief of the “white van commando”, a reference to the vehicles in which journalists were kidnapped to be executed. At least 14 disappeared that way. Since he took power in 2019, police pressure on journalists has seen a worrying resurgence.

Legal framework

Sri Lankan law does not restrict freedom of expression, but guarantees of protection for journalists do not exist. Above all, the 1973 law creating the Press Council, designed to “regulate” the sector, presents a major problem because the president appoints a majority of its members. Officials regularly invoke the anti-terrorism law to silence journalists, especially those who try to report on conditions for the Tamil minority in the island’s north and east.

Economic context

The mass media market is highly concentrated. In broadcasting, the four big firms of the sector share approximately 80% of total viewership. Political authorities exert strong influence on appointments and dismissals of editors-in-chief, whether through political friendships, control over subsidies and advertising contracts or, simply, through corruption. As a result, the most independent news content comes from online networks. Journalists who run them, however, are not exempt from pressure and intimidation.

Sociocultural context

The Sri Lankan press is directed mainly to the Sinhalese and Buddhist majority, who make up three-quarters of the population. Open criticism of the Buddhist religion or its clergy is very dangerous. Prosecutors have used the penal code to imprison journalists suspected of religious hatred. As a rule, treating issues involving the Tamil minority and/or Muslims is considered extremely sensitive. Journalists and media who risked it in recent years have been targeted by arrests, death threats or coordinated cyber-attacks.

Safety

At least 44 media professionals were killed or disappeared over the past two decades, which was marked by the crushing of the separatist Tamil Tiger rebellion. Although journalist murders stopped after 2015, those crimes have gone completely unpunished. The 10th anniversary year of the civil war, 2019, was marked by a troubling increase in attacks on reporters based in the north and on the east coast, the traditional Tamil homeland. Journalists there suffer systematic surveillance and harassment by the police and army. These areas are completely closed to independent media.