Sunday Feb 15, 2026

Sunday Feb 15, 2026

Wednesday, 10 April 2024 01:22 - - {{hitsCtrl.values.hits}}

This article is part of the spring 2024 edition of the Brookings Papers on Economic Activity, the leading conference series and journal in economics for timely, cutting-edge research about real-world policy issues. Research findings are presented in a clear and accessible style to maximise their impact on economic understanding and policymaking. The editors are Brookings Nonresident Senior Fellows Janice Eberly and Jón Steinsson

By Serkan Arslanalp, Barry Eichengreen, and Peter Blair Henry

www.brookings.edu: At a time when many countries, large and small, are confronting heavy and growing public debt burdens, Jamaica offers a rare example of a country that succeeded in substantially reducing its debt, according to a paper discussed at the Brookings Papers on Economic Activity (BPEA) conference on 28 March.

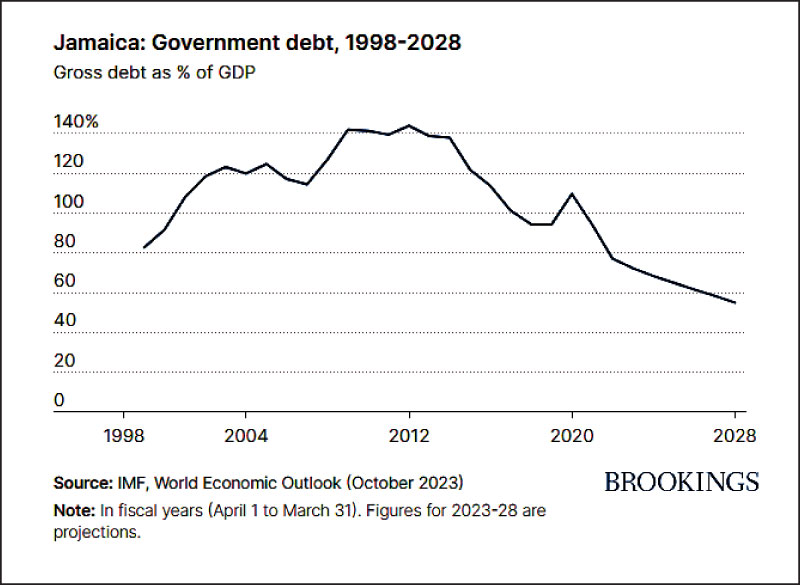

Jamaica cut its debt, as a percentage of its gross domestic product (GDP), in half—from 144% in 2012 to just 72% in 2023, according to the paper—”Sustained Debt Reduction: The Jamaica Exception.” And the International Monetary Fund (IMF) expects Jamaica’s debt ratio to decline still further, to less than 60%, by 2028.

The authors—Serkan Arslanalp of the IMF, Barry Eichengreen of the University of California-Berkeley, and Peter Blair Henry of Stanford University—examine how and why Jamaica succeeded and whether its success can be replicated by other countries.

First, Jamaica adopted fiscal rules that highlighted the debt problem, encouraged the formulation of a medium-term plan, and limited slippage from the plan’s targets. The Fiscal Responsibility Framework introduced in 2010 required the minister of finance, by the end of the financial year 2016, to reduce the budget deficit to zero, the debt-to-GDP ratio to 100%, and public-sector wages as a share of GDP to 9%. The framework as augmented in 2014 required the minister, by the end of financial year 2018, to specify a multi-year trajectory to bring the debt-to-GDP ratio down to 60% by 2026. It included an escape clause to be invoked in the event of large economic shocks, which prevented the rule from being so rigid that it lacked credibility, the authors write.

Second, Jamaica’s leaders leveraged the country’s success in sharply reducing political polarisation since the end of the 1970s. The government, parliamentary opposition, and other stakeholders in 2013 formed the Partnership for Jamaica Agreement, which fostered a common belief that the burden of debt reduction would be widely and fairly shared. The Agreement supported the creation and ensured broad national acceptance of the Economic Programme Oversight Committee to monitor and publicly report on fiscal policies and outcomes, and to provide independent verification that all parties kept to the terms of their agreement.

“Meaningful debt reduction was accomplished only when Jamaica put in place two prerequisites: a set of rules anchoring fiscal policy … and a series of partnership agreements. … Both elements were needed,” the authors write.

They also examine three other countries that achieved significant debt reduction—Ireland in the late 1980s, Barbados starting in the 1990s, and Iceland after its 2008 financial crisis—by successfully pursuing a similar approach.

The authors conclude that partnership agreements such as in Jamaica are most likely to be achieved in smaller countries where it easier to bring relevant stakeholders to the negotiation table. And they are most prevalent in small, open economies dependent on a few economic sectors and thus vulnerable to shocks, making cooperation on fiscal adjustment urgent.

Our “observations leave us relatively pessimistic about the efficacy of fiscal rules in countries such as Germany, whose provisions lack flexibility,” the authors write. “And they leave us concerned about the scope for sustained fiscal consolidation in large countries like the United States with high levels of political polarisation.”

(Source: https://www.brookings.edu/articles/sustained-debt-reduction-the-jamaica-exception/)

(Serkan Arslanalp is Advisor – International Monetary Fund; Barry Eichengreen is Professor – University of California, Berkeley and Peter Blair Henry is Senior Fellow – Hoover Institution and Freeman Spogli Institute, Stanford University.)