Saturday Feb 14, 2026

Saturday Feb 14, 2026

Friday, 19 July 2024 00:22 - - {{hitsCtrl.values.hits}}

Taxpayer rights have been steadily curtailed in recent policy changes

Introduction

Introduction

A taxpayer is required to file, a return of income, VAT return or SSCL return as the case may be on or before the due date. If the Inland Revenue officers are not in agreement with the return filed, they have a statutory right to raise an appropriate assessment on or before the expiry of the relevant time bar provided in the relevant statute. Generally, within a 30-day period a taxpayer of receipt of assessment has to appeal/request for administrative review against such to CGIR, specifying the grounds of appeal. Taxpayers dissatisfied with an assessment have recourse through a four-tier appellate system.

Tax assessment process – general

The tax assessment process commences with an inquiry, which may involve interviews and requests for documents. Following this, the Assistant Commissioner responsible for the taxpayer’s file may issue an assessment if they determine that the declared tax liability is incorrect.

Initially, the taxpayer can request for an administrative review from/appeal to the Commissioner General of Inland Revenue (CGIR). The CGIR will consider written and oral submissions before rendering a decision on the assessment raised against the taxpayer.

The dissatisfied taxpayers may appeal to the Tax Appeals Commission, an independent body that adjudicates disputes of fact and law. Further appeals on legal matters can be directed to the Court of Appeal and ultimately the Supreme Court which is the highest and final superior court in Sri Lanka.

In addition to the tax appellate process, taxpayers can seek judicial intervention through writ applications. The courts may intervene inter alia, if there is a breach of natural justice, infringement of fundamental rights, or if tax officials have improperly denied legitimate benefits of the taxpayer.

Time bar for raising of assessment and lodgement of appeal

Tax laws establish specific timelines for tax authorities to issue assessments and for taxpayers to appeal these assessments to higher authorities, such as the CGIR, Tax Appeals Commission, Court of Appeal, and Supreme Court.

Precisely adhering to these deadlines is crucial. Assessments issued beyond the stipulated timeframe (time-barred) could be challenged and potentially overturned. Further, missing these deadlines can result in taxpayers losing their right to appeal right and incurring substantial financial burden.

Financial professionals must diligently monitor these deadlines to protect the financial interests and mitigate potential financial risks.

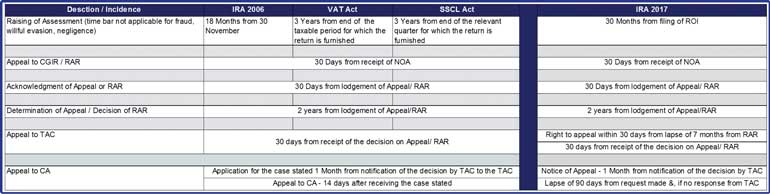

The timeliness specified for key incidences in the Inland Revenue Act No. 10 of 2006, Inland Revenue Act No. 24 of 2017, Value Added Tax No. 14 of 2002 and Social Security Contribution Levy Act 25 of 2022 are summarised in the given table.

Once an assessment is raised under IRA 2017, in general it would take approximately 1.5 years for administrative review and to obtain determination from Tax Appeals Commission. Timeline assumes efficient handling of raising of assessment, appeal/administrative review, including timely filing, prompt scheduling of a hearing, and a relatively reasonable time taken for decision from the Tax Appeals Commission. Thereafter the process can extend significantly if legal complexities necessitate appeals to higher courts (Court of Appeal and Supreme Court).

Burden of proof

The taxpayer bears the responsibility of proving that a tax assessment issued by the CGIR is excessive, as outlined in S.141 of IRA 2017 and S.9 of the Tax Appeals Commission Act, No. 23 of 2011. This legal principle is supported by Court of Appeal judgments, in the cases such as Peoples’ Leasing and Finance PLC v. Commissioner General of Inland Revenue and Brooky Diamond (Private) Limited v. Commissioner General of Inland Revenue. However, there’s an exception: S176 (4) of the IRA 2017 places the burden on the CGIR to justify the imposition of penalties, requiring them to demonstrate non-compliance with the provisions of the IRA, 2017 by the taxpayer.

Further if the CGIR alleges tax evasion, the burden of proof shifts to CGIR to substantiate their claim. This principle aligns Indian legal precedent in the case of Sati Oil Udyog, where the court ruled that the tax authority must provide evidence to substantiate claims of tax evasion.

Power dynamics in the tax system

Taxpayer rights have been steadily curtailed in recent policy changes. For instance, while previously given 30 months to amend tax returns, the IRA 2017 now restricts taxpayers to a 12-month window for filing amendments to the return of income. Simultaneously, the government has extended its time bar to raise assessment from 18 to 30 months, shifting the balance of power towards tax authorities and away from taxpayers.

The IRA 2017 allows taxpayers to appeal to the Tax Appeals Commission within seven months if they did not receive a determination. However, recent amendments have established a two-year period for the tax authority to provide a determination. If a determination is not issued with two-year period, it is automatically deemed appeal is granted unless an appeal has been referred to the Tax Appeals Commission after expiry of seven months period from filing for Administration Review. In the context of this legal framework, as a strategy a taxpayer may refrain from exercising above provision to benefit from the beneficial provision.

Policy proposal in the Budget speech 2024 presented in the parliament last November, outlines the intention of the policy makers to restrict the submission of documentary evidence at the hearing of Tax Appeals Commission. Tax officials can request documents during tax audits or administrative reviews, but taxpayers must provide them within specific timeframes (six months domestically, nine months internationally). Failure to do so will prevent the submission of these documents during the appeal process. This proposed amendment to the Tax Appeals Commission Act is expected to expedite tax assessments and administrative reviews. However, it may also limit taxpayers’ ability to present crucial evidence to an independent body during appeals.

To appeal to the Tax Appeals Commission, taxpayers must currently provide a substantial financial security, as a non-refundable 10% or a refundable 25% bank guarantee. This being a first independent forum one may opine where taxpayer seek justice for his grievances, it is important access to these forums without cost. Imposition of cost to seek justice could unfairly impede access to justice. This financial barrier can impede access to justice, particularly for those with limited resources.

Unlike the IRA 2006, which allowed taxpayers to defer tax payments pending an appeal and imposed a limited 50% penalty, the IRA 2017 mandates immediate tax payment even when an appeal is filed. Taxpayers under the IRA 2017 must pay the assessed tax in full unless granted an extension, which is subject to potentially unlimited interest charges. This financial burden would again unfairly impede access to justice.

Unlocking the bottlenecks: Speeding up tax appeals

While Sri Lanka’s tax appeals process is relatively sound, challenges persist due to understaffing within the tax authority. These issues contribute to delays in assessments and unfair administrative reviews. Addressing these staffing deficiencies is crucial for improving the overall efficiency and fairness of the tax system.

Policymakers could consider shortening the assessment timeline from the current two years to the previous eighteen months or even shorter, contingent on improving the Inland Revenue Department’s capacity. This move is expected to boost investor confidence and stabilise the tax system. Furthermore, the process of issuing tax determinations, currently taking up to two years, should also be accelerated.

To streamline the appeals process, amendments to the Tax Appeals Commission should be contemplated. These changes may include shorter timelines for initial hearings and determinations, as well as the integration of online hearing procedures and evidence submission.

Strict adherence to the Tax Appeals Commission Act’s composition (i.e. The Tax Appeals Commission is composed of a maximum of nine members. Among them, three are retired Supreme Court or Court of Appeal judges, while the remaining six are individuals with extensive expertise in taxation, finance, and law) and the proposed establishment of a tax ombudsman in the Budget speech 2023 and a special tax appeals court as proposed in Budget speech 2021 are crucial for enhancing the efficiency and fairness of the tax appeals process. These measures can expedite dispute resolution, ensuring timely justice for taxpayers.

(The writer is Associate Director (Tax) KPMG. She holds an LLB (University of London), is Fellow Member of Association of Chartered Certified Accountants (FCCA, UK), Associate Member of Chartered Institute of Taxation (ACIT), CA Sri Lanka – Passed Finalist. She also holds an Advance Professional Certification in Transfer Pricing – International Bureau of Fiscal Documentation, Netherlands, Masters of Financial Economics (University of Colombo), MBA in Information Technology (University of Moratuwa), and BSc. Information and Communication Technology (University of Colombo, School of Computing).)