Monday Feb 16, 2026

Monday Feb 16, 2026

Tuesday, 21 August 2018 00:00 - - {{hitsCtrl.values.hits}}

By Gamini Weerasinghe

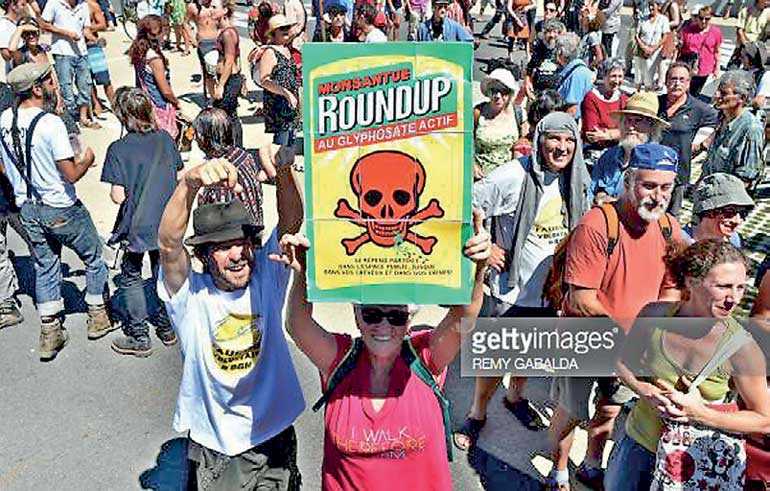

After the recent landmark order delivered by a court in San Francisco, US, where cancer patient Dewayne Johnson, who was ruled to have developed the disease through regular contact with glyphosate, was awarded compensation of $ 289 million (Rs. 46,529 million), another 5,000 cases have been filed by victims against Monsanto, the producers of glyphosate in the US.

Portugal and the city of Vancouver in Canada have banned the weedicide. Even in the EU views on whether to use glyphosate or not are divided with France and Belgium opposing it and Germany and Poland being lukewarm about its dangers.

Current glyphosate-resistant crops includesoy, maize (corn), canola, alfalfa, sugar beets, cotton and wheat. Produced in the US, they were genetically modified to be herbicide-tolerant. This glyphosate resistance enables farmers to wipe out most weeds from the fields without damaging their crops but cannot prevent the herbicide from being absorbed into edible crops and produce.

It was also reported that Prof. Channa Jayasumana of Rajarata University, along with others, is looking to file legal action seeking compensation for victims in Sri Lanka.

In all probability, litigation will snowball worldwide and the producing companies might put up their shutters. US sanctions against Iran and the crisis over Turkey’s currency the Lira has impacted Colombo tea auction prices. All point to the grey clouds that are looming for the tea industry. Let us reach out for the umbrellas and unfold them.

In this scenario, it would be prudent to do research and plan to face any eventuality in case there is no glyphosate. The recent ad hoc decision to ban the weedicide in Sri Lanka resulted in great losses for the tea industry. It is incumbent upon the Tea Research Institute (TRI) and other research institutes to come up with solutions and alternatives in the event of such an eventuality.

There are only very few planters of the pre-weedicide era of the 1960s who are still up and about. I am fortunate to be one of them and I even attended the launch ceremony of the product at Hotel Topaz in Kandy in 1976.

Prior to the advent of weedicides, all weeding, which is a non-productive activity, was done manually. Usually it was given out on contract and paid for monthly. The normal rate was four workers per acre (10 workers per hectare). There were contractors who kept their contracts very clean. I wonder whether this practice would be economically viable and also whether workers could be induced to take on contracts.

The old planters in that decade were very particular about the adage ‘one month’s seed is six months’ weeds’. A weed seed can stay alive for 30 years until the proper conditions conducive to its growth are made available, usually when the soil is disturbed. My superintendent at the Mattakelle Estate, Talawakelle, Derrick Brown, insisted that the soil should not be disturbed to expose the hidden devils. He introduce a small-three pronged implement just to remove the weed. The high profits of Mattakelle were due to the foresight of securing and nurturing the top soil. The estates that have used mammotees or ‘shorandies’ have lost their top soil with disastrous consequences.

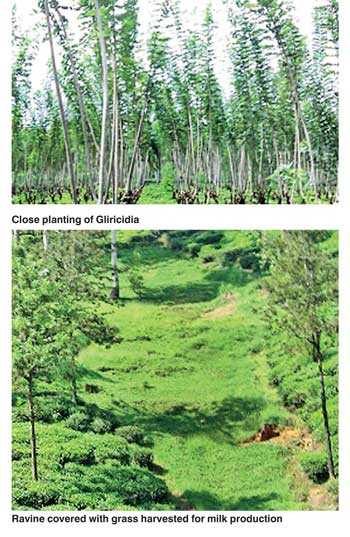

The areas that are exposed to sunlight, and thus produce most of the seed, are the ravines and roadsides. I planted pasture grass in all these areas and it should be noted that my estate recoded the lowest cost in weeding across the whole regional board while the second lowest was three times my cost. Somebody cut the pasture grass which had covered the ravines and produced much-needed milk.

It is also necessary to cover the ground so as to starve the weed of sunlight. Here a great amount of concentration and discipline is needed in plucking so as to establish the cover by tending to the side branches.

Again, to restrict the sunlight, proper shade should be established and maintained. I have planted Dadaps and Gliricidia at 5’X 5’ and lopped one row every three months. This provides the same amount of sunlight to the tea bush and covers the ground with its branches and thatch. Gliricidia gives 2-3% nitrogen from its lopping. Glyphosate was first introduced to tea cultivation in the 1980s for the control of problem weeds such as Couch (Panicum Ripen) Illuk grasses. Higher dosages of glyphosate (36%) at 11 and 5.5 litres in 600 of water per hectare were recommended to control Couch and Illuk grasses, respectively.

It was never envisaged at that time to be used for the control of all weeds. Around that time I found that Bracharia Brizantha has an allopathy to cootch grass and that this pasture grass kills the troublesome Couch. The findings were acknowledged by the TRI and there was also a mention in international magazine Farming of Netherland.

The best way to improve the soil is to have livestock as demonstrated by Mark Bostock on Aislaby. In fact, one person, Shelton Perera, proprietor of Blinkbonny Estates, even used sheep to graze on the weeds in the tea fields and on another estate they used pigs.

Demonstrations in France

Demonstrations in France

Diversification

At this time there is something to think about for ‘C’ category fields which eat into the profits of an estate. Land is a great asset that cannot be produced. Let us make the best use of it. Use the land and concentrate on the good tea and the balance can be diversified for more profitable ventures. It will also solve the problem of a shortage of labour on most estates for the coat has to be cut according to the cloth available.

Livestock

The most common areas that propagate weed seeds on an estate are the ‘C’ category fields with their lack of ground cover due to the poor stand and debilitated bushes. The top soil has been washed way.

It is seen from the records given that about 20-25% of the income derived from tea is spent on the importation of milk and milk foods that can easily be produced in this country.

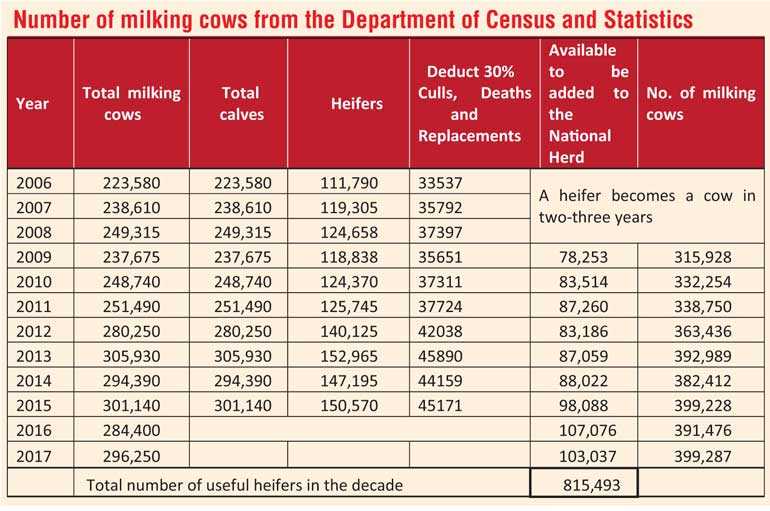

It was also stated that we need only 400,000 cows at the present level lits/cow/day of 3.2 to be self-sufficient in milk. It can also be seen from the chart produced that during the last decade we have lost 800,000 heifers (female calves), which would have made Sri Lanka self-sufficient in milk and save 20-25% of the foreign exchange earned through tea.

The daily manure production of a cow is about 15-20 kg of dung at 4-5% Nitrogen and around 7-10 litres of urine which will improve the soil.

The Government has given every encouragement to the dairy farmers to improve the industry by giving soft loans from the Central Bank and the Ministry of Social Welfare and Primary Industries. The TRI has advised me that if fodder/pasture is to be planted it is not necessary to uproot the tea. The Department of Animal Health and Production is on record saying that the next profitable crop after potatoes is grass which costs about Rs. 1.80 per kg and I know that Hatton dairy farmers are purchasing fresh grass at Rs. 4 with the transport on the buyer’s account. The grass they get is of low quality. It would cost about Rs. 500,000 to plant a hectare of grass and a harvest of 40,000-60,000 kg/ha/year can be obtained from Hybrid Napier grass of CO3 or Bana.

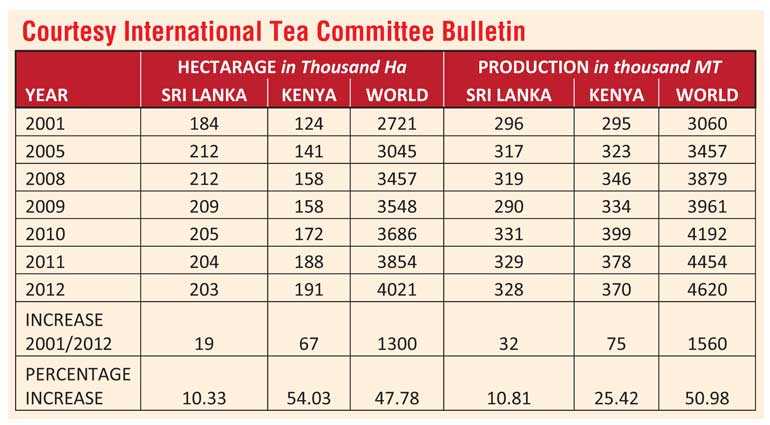

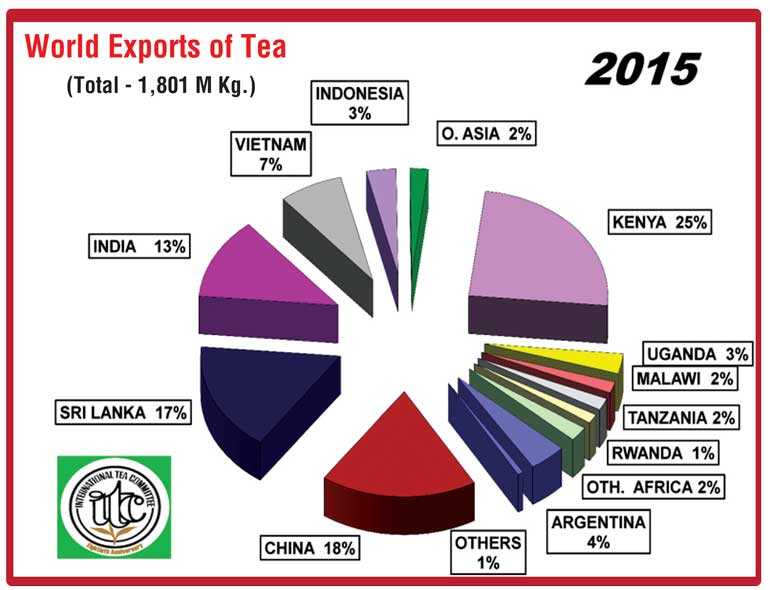

There is a question as to whether the tea industry can survive with competition worldwide as can be seen from the chart below. Sri Lanka also does not produce adequate CTC teas where there is global demand. The COP is also the highest among all producing countries. It can be noted that only 17% of the total exports of tea in the world now come from Sri Lanka while other countries, especially African countries, are forging ahead. Some of them do not use any weedicides at all as plenty of cheap labour is available for manual weeding.

Cinnamon, spices and fruits

Sri Lankan Cinnamon, which is a coumarin-free product, is in great demand. It is the only cinnamon that is allowed to be imported to the European market.

There are many others spices like ginger, turmeric, vanilla and fruits like avocado, jak, marmalade oranges, grapefruit, soursop and the like that could be planted on these lands with economic advantage.

The tea industry and the planters have weathered many a storm during the last 150 years and it is hoped that it will rise to the occasion once again.

(The writer is a former planter with 38 years’ experience. He was the Deputy Director General of SLSPC, Director of JEDB and consultant to NLDB. He can be contacted on 0718387895 or through [email protected]).