Thursday Feb 19, 2026

Thursday Feb 19, 2026

Wednesday, 30 June 2021 00:00 - - {{hitsCtrl.values.hits}}

Just 18 hours after landing in the country in June 1987, David Gladstone had an audience with President J.R. Jayewardene. All too soon, the President had taken him into his confidence

“Be not afeard; the isle is full of noises,

Sounds and sweet airs, that give delight and hurt not”

– William Shakespeare, ‘The Tempest’ –

By Chandani Kirinde

|

The book gives Gladstone’s side of the story along with his other experiences serving in Sri Lanka

|

Retired diplomats spending their days penning down their memoirs recounting their heyday of holding fort among the rich and powerful in foreign lands is not unusual. But then how many among them have had the dubious honour of being declared ‘persona non grata’ by a host nation and given marching orders after being accused of crossing the line into territory that is out of bounds for diplomats?

David Gladstone who served as Britain’s High Commissioner to Sri Lanka between 1987-1991 is one such man who had to face the wrath of the then President Ranasinghe Premadasa for his “unwarranted interference in an internal matter of the country” that resulted in his unceremonious send-off.

Thirty years ago, while the story of Gladstone’s expulsion made headlines, not only in Sri Lanka, but worldwide, the man at the centre of the storm has said little about it; that is, until he decided a few years ago to write a book titled ‘A Sri Lankan Tempest – A Real Life Drama in Five Acts,’ giving his side of the story along with his other experiences serving in Sri Lanka.

Tempestuous years

The years Gladstone served as High Commissioner in Sri Lanka were among the most tempestuous in the country’s post-independence era. He had arrived in June 1987, a month before the signing of the Indo-Lanka Accord. What Britain’s Foreign & Commonwealth Office (FCO) wanted was to consign him to the ‘quiet colonial backwater’ that was Ceylon, Gladstone writes that what he got instead was a full glare of the spotlight.

From Gladstone’s prologue to the book, it is clear that he gauged early on that his stint in Colombo was going to be anything but monotonous. One of his first outings as High Commissioner was watching the Guard of Honour accorded to visiting Indian Prime Minister Rajiv Gandhi on 29 July 1987, in Colombo. It was a day neither Gladstone nor the rest of the world would forget.

A disgruntled naval rating, angry that Gandhi had come to Colombo to sign the Accord that put Indian troops on Lankan soil, took the drastic step of swinging his rifle at the Indian leader. Quick reflexes saved Gandhi that day, but for Gladstone it was “an unusual introduction” to a new post which set the tone for a “most unusual four-year tour of duty”.

The President’s confidant

The President’s confidant

From the inception, Gladstone had the ear of the movers and shakers in Sri Lanka’s political establishment at the time. No doubt being the representative of Great Britain, which for over a century ruled the island, placed him in a more pivotal position than his other diplomatic colleagues in Sri Lanka.

Gladstone underscores the point in his book when he says that just 18 hours after landing in the country, he had an audience with President J.R. Jayewardene or JR as he was known by all. It was the day he presented his credentials and all too soon, the country’s all-powerful executive President had taken him into his confidence.

Of their first meeting Gladstone writes, “Cutting short the customary formalities, he (JR) guided me to a corner of the State room where he unburdened his political preoccupations with remarkable candour as if I were an old and trusted confidant rather than a foreigner he had just met.”

What he unburdened on the newly-appointed High Commissioner was the well-kept secret that he had proposed to Rajiv Gandhi that the two Governments sign an “Accord” under which the Indian Government would stop supporting the Tamil Tigers and instead help control them by stationing Indian troops in the north. JR had sought the understanding and support of the British Government in this endeavour.

While Gladstone was privy to the news of the Accord, most Sri Lankans were in the dark about the signing of an Accord with India. The violent fallout created by the Indo-Lanka Accord not only caused mayhem and discord in the country but set the stage for a worsening law and order situation.

These were early days in Gladstone’s tour of duty in Colombo but major changes in the country’s political landscape were not too far away and the special status accorded British High Commissioners in Sri Lanka demonstrated by President Jayewardene would soon end with a new administration taking office in the country.

There’s no doubt had JR remained in office, Gladstone’s fate would have been an altogether different one. As the author points out, JR retained a strong affection for Britain despite his youthful wartime escapade, that of offering his services as a “collaborator” in the event of a Japanese occupation of Ceylon during the Second World War.

One of JR’s greatest ambitions, he had disclosed to Gladstone, was to be accorded a State Visit to the United Kingdom and to “ride down the Mall with the Queen in a golden coach”. Gladstone had put JR’s request to the FCO only to be told that the programme for State Visits was full for the foreseeable future but they would be happy to invite him as Head of Government rather than Head of State. JR would receive all the honours accorded to a Head of State but not be the Queen’s guest and would not be able to ride in Her Majesty’s coach. “JR was crestfallen when I relayed the message to him. He declined the offer. He had set his heart on the golden coach and nothing less would do.”

Impressions of major political players

Impressions of major political players

Gladstone devotes some pages in his book to describe his impression of the major political players of the country in the late 1980s to early 1990s. These include Sirimavo Bandaranaike, JR’s arch-rival, who was stripped of her civic rights in 1980 to keep her out of Parliament.

Of Mrs. Bandaranaike, Gladstone writes: “I became very fond of her from the moment I encountered her serving food with her own hands to visitors at a religious ceremony in the holy city of Kataragama. I was also conscious that she had singlehandedly stopped the massacre of JVP rebels by the security forces following the 1971 uprising.”

While he is flattering in his take on Mrs. Bandaranaike, he is less so about Ranasinghe Premadasa, the man who succeeded JR as President and under whose tenure Gladstone was literally shown the door.

His references to Premadasa as a boy from the backstreets, a man who fashioned his methods used by the mafia, one who could not be ignored because of his popularity with low-caste voters, someone who would be invited to the homes of political leaders – all of them like the President (JR) from upper-class families – only to be allowed to have his drinks standing up, but “not to sit with them at table” shows a prejudiced take on the late President.

Gladstone acknowledges that he found Premadasa easy to talk to and intelligent and the two got on so well in the early days and that “on learning that trees were one of my passions he insisted on paying an official visit in me at the British High Commission to plant a na (ironwood) tree in my garden.”

Rude awakening and political change

For Gladstone, the start of 1988 brought a rude awakening when actor turned politician Vijaya Kumaratunga was shot dead in February that year. He had met Kumaratunga soon after taking up his post in July 1987 and two weeks prior to the actor turned politician’s death, Gladstone had invited him to his son Patrick’s 20th birthday party.

“He had accepted at once and rather to my surprise actually came. Many politicians in his position would have found a last-minute excuse, but he gave every sign of enjoying himself in the company of young people.”

The following year brought about major political change in the country. After 11 years as Executive President, JR departed and he was succeeded by Ranasinghe Premadasa. It was January 1989 and for Gladstone it meant he would no longer have private time alone with the country’s president. “Premadasa never saw me alone but was flanked by at least two private secretaries who recorded every conversation. It became impossible to discuss developments freely and in confidence and I was given to understand that in future I would not enjoy privileged access.”

Premadasa inherited a country in disarray. At the time the JVP was almost running a parallel administration declaring holidays, curfews and hartals by putting up posters or sending letters. The counter offensive by the Government resulted in a steep rise in extra judicial killings and it was around that time Gladstone had begun to use public fora to speak up on human rights issues.

But Gladstone had to stand alone on this issue with no support from his own Government. In 1990 the promotion of human rights did not figure on the list of the British Foreign Office’s policy objectives and “British diplomats were not expected to report on other Government’s performance,” Gladstone writes.

Gladstone’s fall from grace

Gladstone’s fall from grace

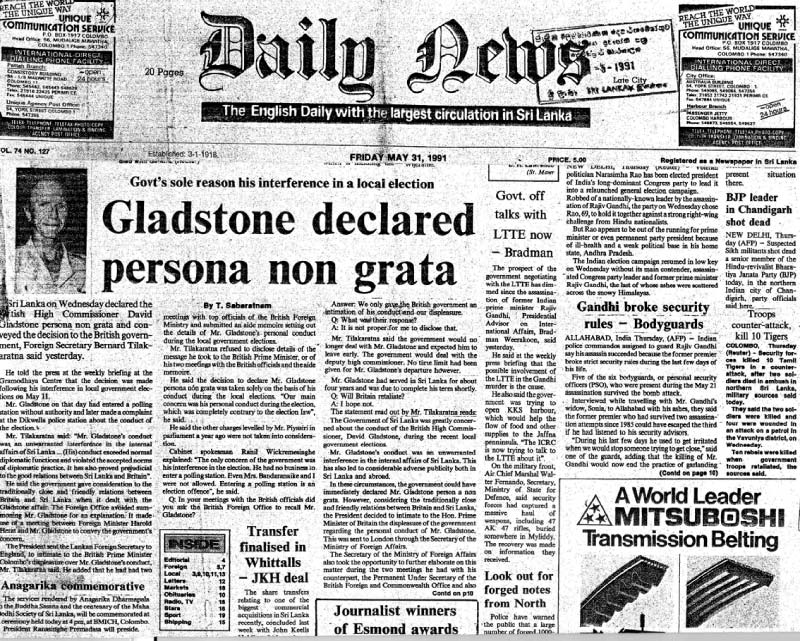

The incident that led to Gladstone being declared persona non grata came about as a result of his conduct during the Local Government Elections held on 10 May 1991.

President Premadasa was keen to ensure that the poll was conducted in a free and fair manner and thought it best to invite international monitors to observe and report on it. The Government’s intention was conveyed to the Ambassadorial Group and as it so happened the British High Commissioner was assigned with the task of monitoring the poll in the Southern Province.

Gladstone describes in great details what transpired on that decisive day.

He had left for Matara on the day of the poll and at Dickwella encountered a group of young Sri Lanka Freedom Party (SLFP) supporters who complained they had been barred from entering the polling booth by thugs of the ruling United National Party (UNP). Gladstone had visited the polling booth in question and the Returning Officer (RO) on duty had confirmed what the young men had said.

The RO had requested Gladstone to join him to lodge a complaint at the Police Station but the British diplomat had initially refused saying he was only an observer and not a part of the election machinery. The RO had insisted and Gladstone, rather reluctantly, had agreed to join him. A statement was recorded at the Police station and Gladstone ended up signing the document.

Gladstone reflects on those crucial moments this way: “No doubt I should have foreseen the consequences; no doubt I should have erred on the side of caution. But faced with a stark choice between affirming what I had witnessed and declining to do so on grounds of diplomatic protocol, I thought of all the bloodshed and disappearances, reprisals and repression that had raged around me for the past four years and it felt a very small step to put my signature to a statement I knew to be true; one moreover that might serve to advance, however modestly, the cause of democracy in Sri Lanka.”

Unceremonious send-off

Unceremonious send-off

There was no immediate reaction from the Government but three days later he heard from the Head of the Foreign Office that the Sri Lankan High Commissioner in London had called on him to complain about Gladstone’s interference in the country’s internal affairs.

Gladstone was not called to the Foreign Affairs Ministry to explain his conduct. Instead, the Government made several attempts to get London to recall their man in Colombo and when this failed, the message was conveyed to the Foreign Office that “Britain’s representative in Colombo was persona non grata and must pack his bags”.

Despite the bitterness caused by the turn of events, the Sri Lanka Government was “generous” giving him 10 days to pack up and leave. As he was readying for his departure, he had a stream of visitors including Gamini Dissanayake and Chandrika Kumaratunga who at the time was still contemplating entering politics.

The unceremonious send-off from Colombo didn’t end his career at the Foreign Office. A few months after his return to the UK, Gladstone was asked to open the first-ever British Embassy in the newly-independent state of Ukraine, an offer which he took up.

Turbulent times continued for Sri Lankan years after Gladstone’s departure and the repercussions of the signing of the Indo-Lanka Accord reverberated outside the country. Rajiv Gandhi was assassinated in May 1991 just days before Gladstone’s expulsion and President Premadasa was assassinated two years later on 1 May 1993, both by the Tamil Tigers.

While the misfortunes that Sri Lanka faced in the ensuing years eclipsed any Shakespearean tragedy, Gladstone’s expulsion, which took place 30 years ago, is somewhat a forgotten episode in a country still struggling to come to terms with the dark days of the period he served here.

The incident that led to Gladstone being declared persona non grata came about as a result of his conduct during the Local Government Elections held on 10 May 1991