Monday Feb 16, 2026

Monday Feb 16, 2026

Monday, 24 June 2024 00:00 - - {{hitsCtrl.values.hits}}

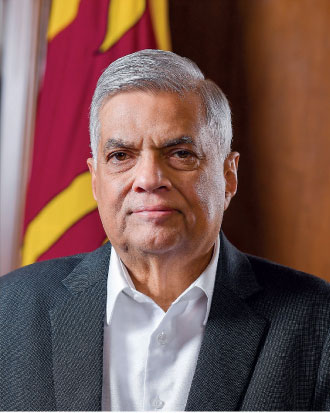

President Ranil Wickremesinghe

Treasury Secretary Mahinda Siriwardena

IMF Sri Lanka Senior Mission Chief Peter Breuer

|

The IMF Tracker maintained by Verité Research allows people to know the progress of actions in the IMF program on a month-by-month basis without having to wait 6-9 months for an IMF review. The last update of the Tracker was for the end of May, and the second IMF Review came out on 12 June, 2024. How did the IMF’s evaluation in the second review compare with the Tracker?

The Tracker has three categories: “Met”, “Unknown”, and “Not Met”. There was one action that the Tracker evaluated as “Met”, which the IMF Review said was “Not Met”. This was on allocating 0.6% of GDP to Social Spending. The Tracker evaluation of “Met” was based on Table 31 of the Annual Report of the Ministry of Finance.

The IMF made a significant positive contribution to Sri Lanka by reinforcing the agenda of governance and anti-corruption in keeping with the overwhelming voice of the people of Sri Lanka. It produced an excellent Governance Diagnostic Assessment, that was very much in sync with the Civil Society Governance Diagnostic Report produced in Sri Lanka.

In this second IMF Review, the analysis against the Tracker shows the IMF to be largely in step, but with a few serious discrepancies. The IMF review implicitly and explicitly evaluates at least 14 actions as “Not-Met”; including 3 actions that the Tracker classified as “Unknown”. But the IMF review has made serious objective mistakes in assessing as “Met”, 4 transparency and anti-corruption-related actions in the current program.

At the end of May, the Tracker evaluated 16 actions as “Not Met”. Exhibit 1 numbers these as A1 to A16. This note by Verité Research staff provides a detailed look at what the IMF review said on these 16 actions classified on the Tracker as “Not Met”.

The “Not Met” Comparison in Summary: The comparison shows that the IMF evaluation either agrees explicitly with the Tracker or is silent on 10 of the 16 commitments that were evaluated as “Not Met”. Of the remaining 6 commitments, it shows the IMF to be mistaken in evaluating 4 of them as “Met”, despite them being objectively “Not-Met” even by 12 June. The 2 remaining “Not-Met” actions on the Tracker are cabinet decisions – where the difference in information available to the IMF and the Sri Lankan public cannot be objectively reconciled.

Detailed analysis of 16 Actions “Not Met” on the Tracker

7 of 16: IMF Review Aligns Explicitly with the IMF Tracker

A1-A7: The IMF review confirms the IMF tracker analysis that these seven commitments were not met.

2 of 16: IMF Review is silent: Remains not met on IMF Tracker

The IMF review does not comment explicitly on A8 and A9.

A8 was a Structural Benchmark to index excise taxes to inflation. This would mean, for instance, that excise taxes on tobacco and alcohol would have been formally indexed to inflation. This has not been done in Sri Lanka, either through law or practical action, and the IMF review is silent on the failure. The commitment has now also been omitted from the program moving forward, which is an exceptional development given its status as a Structural Benchmark and its importance as a revenue measure in a program focused on increasing revenue.

A9 was a Structural Benchmark on publishing the direct cost (revenue loss) of tax exemptions. Verité Research analysed what the Government had published as an expenditure statement and found that it fell well short of expectations. It had shortfalls in both its coverage and computations.

Coverage shortfall: The shortfall was in both duration and scope. In terms of duration, the estimations covered only the period from April 2022 to March 2023. With regards to scope, the document itself listed 26 firms receiving tax exemptions for which estimations had not been made.

Computation shortfall: The computations of some of the tax losses were based on lower tax levels from early 2022, without taking into consideration, for instance, the increase in corporate income taxes in October 2022. Additionally, the revenue lost due to exemptions on PAL and CESS was not calculated.

These shortfalls in computation and coverage were not addressed by the Government even up to the end of May 2024. The IMF review does not comment on this commitment, which might be interpreted as recognising the shortfalls yet choosing not to draw attention to them.

1 of 16: IMF Review is silent: Met after End May date on IMF Tracker

A10 was a commitment that was not met at the end of May when the Tracker was last updated. The IMF review does not comment on whether it was met or not met. However, it was met by the Government on June 7th, a few days prior to the IMF Board meeting that discussed the Sri Lanka program.

4 of 16: IMF Evaluation is objectively mistaken in stating as met.

A11 was a commitment to “Publish audited financial statements of all but five SOEs”. This commitment only applies to what are considered to be 52 strategically important SOEs. The Ministry of Finance, on its website (link below), provides information on what they have published for each of the 52 SOEs. As of 12 June 2024, it clearly lists that 8 of these SOEs have only unaudited statements for 2022, not audited statements (link: https://www.treasury.gov.lk/web/annual-reports-financial-statements-of-key-soes). The IMF review, however, states: “Audited statements of all but five smaller SOEs were available by end-December.” This is at odds with what has been self-declared by the Ministry of Finance.

A12 was a Structural Benchmark that was stated as “Based on the recommendations in the Governance Diagnostic report, published on 30 September we will develop and publish a Government Action Plan by February 2024 (new structural benchmark) to implement all priority recommendations.” The report contained over 100 recommendations, with 16 priority recommendations set out on page 15.

The action plan published by the Government is in the form of a timetable for implementation and is available at https://www.treasury.gov.lk/api/file/5e0c54aa-62cd-4ac3-846a-9073dfc653c6 . It covers only 14 of the 16 priority recommendations. The 2 omitted priority recommendations are particularly important for reducing corruption. They are described below.

First Omission: to “Institute short-term anti-corruption measures within each revenue department to strengthen internal oversight and sanctioning processes and linkages with CIABOC and related criminal investigation and enforcement processes by Dec 2023 and issue a public report on steps taken and results obtained by Dec 2024”.

Second Omission: This relates to one of the most controversial corruption scandals in Sri Lanka involving bond market and stock market transactions of the EPF, where forensic audits published in 2019 exposed huge corruption. The priority action was to “following a broad consultative process, produce a Cabinet policy paper by June 2024 on options for establishing new management arrangements for the Employee Provident Fund that terminates direct CBSL management”.

|

In discussions with Sri Lankan civil society, IMF staff have openly acknowledged that they are aware of the non-compliance with this commitment. Therefore, even though the IMF review reads as if it agrees that the commitment has been met, the wording on the review carefully states that: “Authorities published the Governance Diagnostic report in September 2023 and, based on its recommendations, developed and published an Action Plan in February 2024”. The use of the term “an” instead of “the” might be an artful equivocation, casting a knowing Nelsonian eye on the fact that the action plan published was not the one that was agreed in the program.

In discussions with Sri Lankan civil society, IMF staff have openly acknowledged that they are aware of the non-compliance with this commitment. Therefore, even though the IMF review reads as if it agrees that the commitment has been met, the wording on the review carefully states that: “Authorities published the Governance Diagnostic report in September 2023 and, based on its recommendations, developed and published an Action Plan in February 2024”. The use of the term “an” instead of “the” might be an artful equivocation, casting a knowing Nelsonian eye on the fact that the action plan published was not the one that was agreed in the program.

A13 is a Structural Benchmark and an extensive commitment written out fully in Exhibit 1. It requires the Government to publish, on a semi-annual basis, comprehensive information relating to procurement and tax concessions.

Tax expenditure information shortfall: The tax expenditure information published falls short in several ways, such as: Some tax expenditure calculations are based on 2022 rates rather than 2023 rates; tax expenditures due to CESS and PAL exemptions are not calculated; it acknowledges under-reporting of tax expenditures, citing difficulties in obtaining the requisite data from certain firms, and yet fails to provide estimations of the same.

Procurement information shortfall: The procurement information published, instead of being comprehensive, falls seriously short of even the existing legal requirements in Sri Lanka. These can be seen in Exhibit 2, which lists the proactive disclosure requirements for procurement under the Right to Information Act.

Additionally, large contracts of the Ceylon Petroleum Corporation, with high corruption vulnerability, are reported with a procurement value of zero (not published).

IMF states: “SB on publishing procurement contracts and the list of firms receiving tax exemptions, including the cost of exemptions, was implemented with delay on 13 February, 2024”. This once again seems to be an objective mistake made in the IMF Review, as it is unlikely that the IMF intends to endorse an activity in which the Government falls short of its own laws on information disclosure.

A14 is a Structural Benchmark commitment to introduce, track, and report on 7 Key Performance Indicators (KPIs) related to four core administrative functions to help boost compliance. This commitment can be read fully in Exhibit 1. However, such reporting is not available on any Government website even as of 12 June, 2024, making the IMF Tracker’s assessment of “Not Met” correct.

The IMF review, however, incorrectly states: “The SB on the report on Key Performance Indicators (KPIs) for tax administration (due for end March 2024) was implemented with delay on 8 May, 2024, as the authorities needed time for data preparation.”

How is this discrepancy in evaluations possible? A clue exists in how this commitment has been re-written for the future. It now states, “We will share the data on the quarterly KPIs with IMF staff within two months after the end of each quarter”. Therefore, it seems that instead of reporting performance as committed, the Government has provided relevant data only to the IMF. In addition, the commitment has also been recrafted to remove the reporting requirement in the future and make it permissible to conceal potential failures to meet KPIs on tax administration from public view.

Therefore, the failure to meet the reporting requirement is not accurately captured in the IMF review, and the requirement has also been done away with for the future. If the goal is to improve governance, this is probably not the best way to proceed with the evaluation and amendment of program commitments.

2 of 16: Information on cabinet decisions is not objectively reconcilable

A15 is a Structural Benchmark to obtain Cabinet approval of a strategy to build a VAT refund system and achieve a full repeal of SVAT, with a timeline and intermediate steps. The cabinet decision of the Government is published on the following website: https://www.dgi.gov.lk/news/cabinet-decisions. This is not a decision that would have warranted secrecy (as some cabinet decisions might), as it was committed in the program, and a similar cabinet decision on repealing SVAT was published and given media coverage earlier in 2023.

However, the decision is not published, nor was it announced to the media. Furthermore, the mentioned “strategy” cannot be found on the Inland Revenue website. This was the basis on which the Tracker evaluated it as “Not-Met”

The IMF Review on page 11 lists this commitment under “By end-April, most SBs were either met or implemented with delay”, which is an assessment that it was “Met”.

A16 is a Structural Benchmark to obtain Cabinet approval of a reduction in the limit on Government guarantees to 7.5% of GDP.

A cabinet decision to this effect cannot be found on the Government’s designated website, nor can it be claimed to warrant secrecy as it was a public expectation set in the program.

There was a separate commitment in the IMF program to pass a new Public Finance Management law, which received cabinet approval, and it would, when passed, constrain Government guarantees to 7.5% of GDP from the next budget – 2025 onwards. This program commitment, however, was due in December 2023 with the intention of introducing the constraint by executive decision earlier for 2024 (prior to the law being passed). Therefore, even if “a” decision has been made, and not published, it seems to be different from “the” decision that was envisaged in the program.

The IMF Review on page 11 lists this commitment under “By end-April, most SBs were either met or implemented with delay”, which is an assessment that it was “Met”.