In light of the ongoing visit to Sri Lanka by a delegation from the International Monetary Fund to discuss the resumption of the current lending arrangement, the following article analyses Sri Lanka’s relationship with the organisation

By Adam Collins and Pabasara Kannangara

1. What is the IMF?

- The IMF is a multilateral, international financial institution. It promotes the stability of the international monetary and financial systems. It is distinct from the World Bank, which provides financing to support economic and social development.

- The IMF was conceived in July 19441 at the United Nations Bretton Woods Conference, during the closing stages of the Second World War. The 44 governments represented sought to build a framework for economic cooperation in order to avoid the competitive currency devaluations that contributed to the Great Depression of the 1930s.

- The IMF officially commenced in December 1945, after the first 29 members signed its Articles of Agreement and began operations in 1947. Currently there are 189 member countries who have committed financial resources of $ 692 billion (as of April 2018).2

- The IMF headquarters are located in Washington DC and the institution employs approximately 2,700 people from 150 countries.3

2. The main functions of the IMF

- The IMF has the three main functions:

- Surveillance;

- Capacity Building; and

- Lending.

Surveillance

- The IMF monitors economic developments in member countries and the global economy in order to identify risks to the stability of the international financial system, and recommend appropriate policies.

- Bilateral surveillance involves regular visits (usually annual)4 to member countries, which are known as Article IV consultations. During these visits IMF staff engages government officials and stakeholders in discussions related to local economic and financial developments. An Article IV consultation report is issued shortly after, detailing the findings of the visit.

- The IMF’s multilateral surveillance involves continuous research by IMF staff on emerging economic issues, and the publication of several regular reports on global economic trends.

Capacity Building

- IMF capacity building involves technical assistance (economic institution building) and human capacity development (training).5 It is provided to strengthen institutional capacity in member countries, and is demand driven.

- Capacity building assistance is focused on four areas;6 fiscal policy, monetary and financial sector policies, legal frameworks, and statistics.

Lending

- A member country may request IMF financial assistance if there is a lack (or potential lack) of sufficient foreign currency financing available on affordable terms, to meet its net international payments. This situation can be triggered by a variety of domestic and external factors, in combination or separately.

- The process of obtaining IMF financial assistance is as follows:

- After a request for financial support from a member country, an IMF staff team holds discussions with the government to assess the economic situation.

- Typically, a country’s government and IMF staff must then agree on a program of economic policies to be implemented in return for a loan.

- Once an understanding has been reached on the terms of the loans and the program of economic policies, a recommendation is made to the IMF’s Executive Board to extend access to IMF resources. Depending on the type of arrangement, this could be in phased instalments or as a single disbursement.

- The majority of IMF loans come from the IMF’s General Resources Account (GRA),7 which is funded by subscription charges to member countries. The two main lending facilities are Stand-By Arrangements (SBA), which address short-term balance of payments problems, and the Extended Fund Facility (EFF), which focuses on longer-term difficulties with external payments.

- Loans are given either on non-concessional terms, with an interest rate close to market rates, or on concessional terms, with a zero-interest rate, for low-income countries.

3. How is the IMF governed?

- IMF governance is based on a system of quotas that determine the financial resources each member country must contribute to the organisation, how much they can borrow from the IMF, and their voting power in the IMF’s decision-making bodies.

- The quota of a country is first, calculated8 as the weighted average of a country’s Gross Domestic Product (weight of 50%), openness (weight of 30%), economic variability (weight of 15%), and international reserves (5%). A compression factor is then used to reduce the dispersion in the final quota shares.

- These quotas are expressed in Special Drawing Rights (SDR). This is an international reserve asset, as well as the unit of account used by the IMF and other international organisations.

- The IMF has three decision making organs:

- The Board of Governors has a representative from each member country and has the power to appoint members to the Executive Board, suspend membership, and amend the IMF Articles of Agreement.

- The Executive Board has 24 Directors and is chaired by the IMF Managing Director in a non-voting capacity. It is responsible for most formal decisions and has a supervisory role over the Managing Director and technical staff.

- The Managing Director is selected by the Executive Board. They have a dual role as a Chairman of the Executive Board and as the head of technical staff.

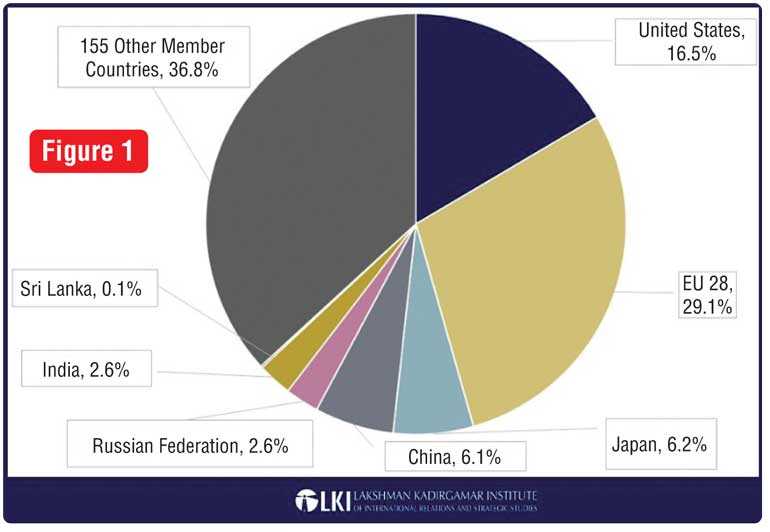

- The voting power of each country on the IMF’s Board of Governors is composed of basic votes, and one additional vote for each SDR 100,000 of their quota.9 As a result, voting power is skewed in favour of larger and more open economies.

- In addition, while the United States, Japan, Germany, France, United Kingdom, China and Saudi Arabia have their own permanent Directors10 on the Executive Board, the remaining member countries are grouped into constituencies, and must agree on a common Director.

4. Critiques of the IMF

- The governance structure of the IMF has been criticised as the voting power is skewed11 towards major European economies and the US. (See Figure 1.) This stands in contrast to the United Nations and the World Trade Organization, who follow a One Nation, One Vote system.

- This has led to some allegations of excessive political intervention and unfair treatment of some members. For example, a report done by the Independent Evaluation Office12 of the IMF, found that during the Eurozone crisis, some measures were made more favourable to the countries that had greater influence over the organisation’s decision making bodies.

Conditionality of Lending

- Most IMF lending arrangements are conditional on the member country involved agreeing to implement a set of economic policies approved by the IMF. This is to reduce the risk of default on loan repayments and minimise moral hazard.13

- However, the conditions imposed by the IMF in the past, such as sharply reducing government spending, have been criticised as it is damaging to social welfare and long-term economic development. What’s more, some have called the use of conditions undemocratic due to their imposition by a supranational organisation with a governance structure skewed in favour of a small number of economies.14

5. Sri Lanka’s relationship with the IMF

- Sri Lanka joined the IMF on 29 August 1950 as the organisation’s 50th member.15 It currently has a quota of SDR 578.80 million,16 equivalent to around $ 800 million. This gives Sri Lanka a voting share of 0.14 on the IMF’s Board of Governors and it shares a common Director18 on the Executive Board with Bangladesh, Bhutan and India.

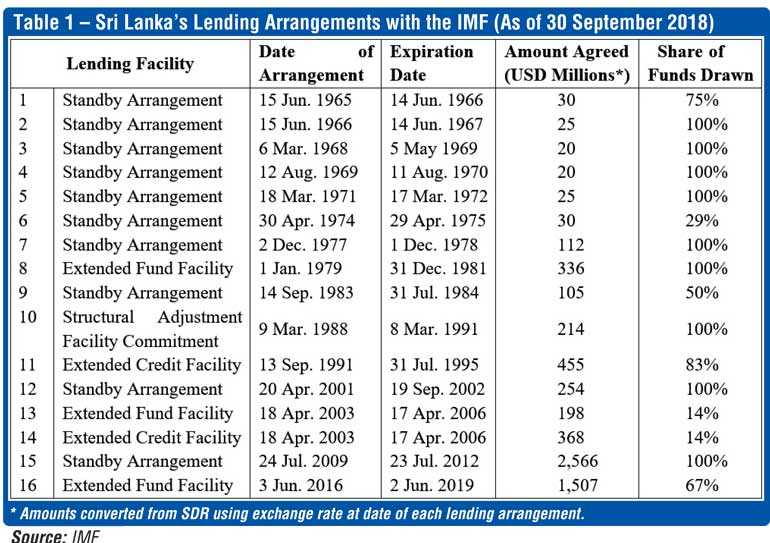

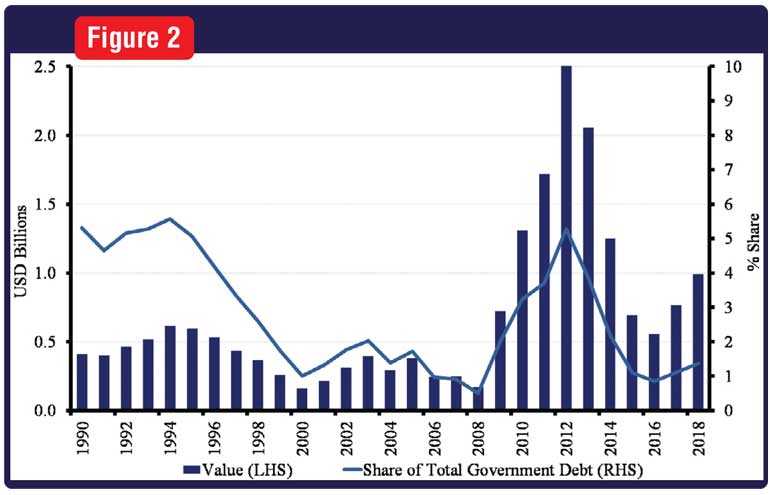

- Since joining, Sri Lanka has been the recipient of 16 IMF loans,19 including the most recent arrangement initiated in June 2016 (See Table 3). The largest loan was the SBA initiated in July 2009, which was worth over $ 2.5 billion.20 In comparison, Pakistan has been involved in 21 IMF lending arrangements,21 most recently a $ 6 billion EFF agreed in September 2013.

- Of the 15 past lending arrangements, the full amount initially agreed was not disbursed on six occasions as Sri Lanka did not fully comply with the conditions of the loans (see lending arrangements 1, 6, 9, 11, 13, 14 in Table 1). The most recent case was the combined EFF and Extended Credit Facility agreed in April 2003, which was disrupted by the Indian Ocean tsunami, in December 2004.

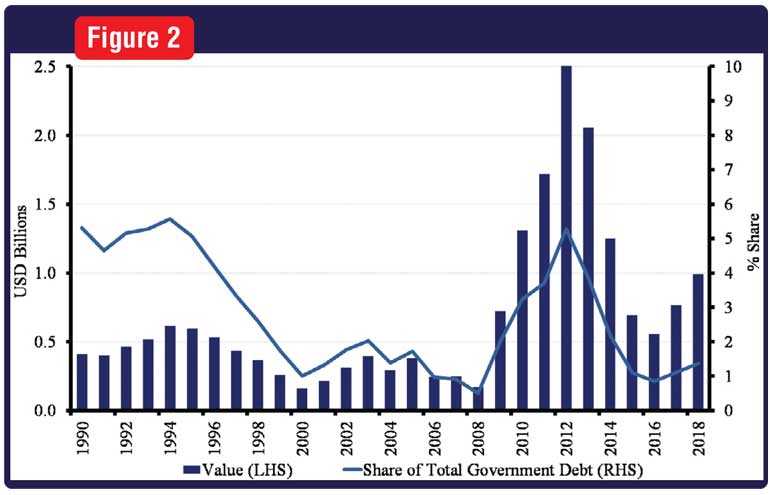

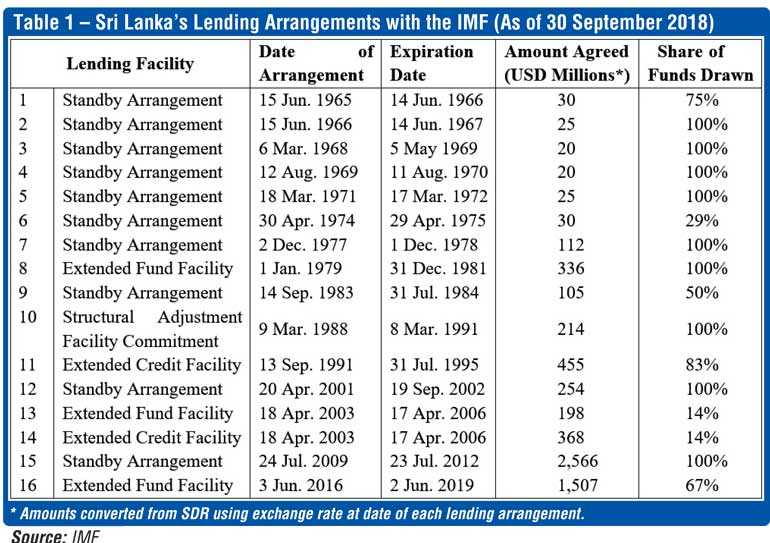

- Sri Lanka’s debt to the IMF peaked at $ 2.5 billion in 2012,22 which was around 5% of the government total debt burden at the time (See Figure 2). Even accounting for the initial disbursements of the ongoing lending arrangement that was initiated in June 2016, debt to the IMF only made up around 1.5% of the total government debt at the end of 2018. Sri Lanka has never failed to repay IMF debt on time and has never defaulted.23

- The Sri Lankan government, including the Central Bank, have received numerous technical assistance missions24 from the IMF since it became a member. These have covered areas such as tax administration, macroeconomic forecasting, the drafting of new income tax legislation, financial sector regulations, and improving national statistics.

6. Sri Lanka’s current IMF Program

- On 3 June 2016, the Executive Board of the IMF approved the Sri Lankan Government’s request for a 36-month lending arrangement under the EFF lending facility.25 This was worth SDR 1.1 billion, which was equivalent to around $ 1.5 billion at the time, and was smaller than the lending arrangement agreed in 2009.

- The Sri Lankan authorities requested the loan for three reasons:

1.To deal with immediate balance of payments pressures

Prior to its announcement,26 a persistent current account deficit, combined with weaker FDI inflows and capital outflows from the local government bond market had contributed to a substantial fall in the Sri Lanka’s foreign exchange reserves. This situation was not sustainable, and put the government at the risk of being forced to restrict imports, as well as default on external government debt repayments due to a lack of foreign currency. The loan from the IMF directly contributed to raising the country’s foreign exchange reserves at an affordable cost.

2.To unlock other financing

The conditions associated with the lending agreement reinforced the government’s policy credibility and at the time of signing was expected to catalyse an additional $ 650 million27 in other multilateral and bilateral loans.

3.To reassure private investors

The lending agreement reduced the probability that the government would default on its existing debts and as a result contributed to a fall in the interest rate private investors required the government to pay on its bonds.28 This allowed the government to obtain further financing at a more affordable rate.

The conditions attached to the current EFF29 lending arrangement aim to ensure future macroeconomic stability. In particular, they focus on raising government revenues in order to reduce the budget deficit and debt burden, increasing foreign exchange reserves, and improving public finance management.

- Following an initial disbursement of around $ 0.17 billion30 in June 2016, the remainder of the loan was scheduled for release in six semi-annual instalments. These payments are disbursed based on the government making satisfactory progress in implementing the agreed reforms, which is assessed through regular program reviews by the IMF.

- On 1 June 2018, the IMF Executive Board completed the fourth semi-annual review31 of Sri Lanka’s economic performance under the EFF arrangement. This enabled the disbursement of SDR 177.7 million (around $ 252 million) and brought the total amount disbursed to SDR 715.2 million (around $ 1,014 million). At the time of writing, the fifth semi-annual review was under discussion.

- The final review and disbursement under the current EFF arrangement is scheduled to take place in April 2019.32 Repayment of the funds borrowed under the arrangement will take place in instalments beginning in 2020, and is expected to be completed by 2028.33

Footnotes

1IMF. (2018). The IMF at a Glance. Available at: https://www.imf.org/en/About/Factsheets/IMF-at-a-Glance.

2Ibid.

3Ibid.

4IMF. (2018). About the IMF: Work: Surveillance. Available at: https://www.imf.org/external/about/econsurv.htm.

5IMF (2018). Fact sheet on IMF Quotas. Available at: https://www.imf.org/external/np/exr/facts/pdf/quotas.pdf.

6IMF. (2018). IMF Capacity Development. Available at: https://www.imf.org/en/About/Factsheets/imf-capacity-development.

7General Department. (2018). 2nd ed. [ebook] IMF. Available at: https://www.imf.org/external/pubs/ft/pam/pam45/pdf/chap2.pdf.

8IMF. (2018). IMF Quotas. Available at: https://www.imf.org/en/About/Factsheets/Sheets/2016/07/14/12/21/IMF-Quotas.

9 IMF (2018). Fact sheet on IMF Quotas. Available at: https://www.imf.org/external/np/exr/facts/pdf/quotas.pdf.

10IMF. (2018). IMF Executive Directors and Voting Power. Available at: https://www.imf.org/external/np/sec/memdir/eds.aspx.

11Carin, B. and Wood, A. (2005). Accountability of the International Monetary Fund. Burlington: Ashgate Publishing Company. Available at: https://www.idrc.ca/sites/default/files/openebooks/175-2/index.html

12The IMF and the Crises in Greece, Ireland, and Portugal: An Evaluation by the Independent Evaluation Office. (2018). IEO. Available at: http://www.ieo-imf.org/ieo/files/completedevaluations/EAC__REPORT%20v5.PDF#page=56.

13IMF. (2018). IMF Conditionality. Available at: https://www.imf.org/en/About/Factsheets/Sheets/2016/08/02/21/28/IMF-Conditionality.

14Grenville, S. (2018). Why is it so hard for the IMF to accept criticism? Lowyinstitute.org. Available at: https://www.lowyinstitute.org/the-interpreter/why-it-so-hard-imf-accept-criticism.

15IMF. (2018). List of Members’ Date of Entry. Available at: https://www.imf.org/external/np/sec/memdir/memdate.htm.

16IMF. (2018). Financial Position in the Fund for Sri Lanka as of October 31, 2018. Available at: https://www.imf.org/external/np/fin/tad/exfin2.aspx?memberKey1=895&date1key=2099-12-31.

17IMF. (2018). IMF Members’ Quotas and Voting Power, and IMF Board of Governors. Available at: https://www.imf.org/external/np/sec/memdir/members.aspx.

18IMF. (2018). IMF Executive Directors and Voting Power. Available at: https://www.imf.org/external/np/sec/memdir/eds.aspx.

19IMF. (2018). History of Lending Arrangements: Sri Lanka. Available at: https://www.imf.org/external/np/fin/tad/extarr2.aspx?memberKey1=895&date1key=2018-09-30.

20Ibid.

21IMF. (2018). History of Lending Arrangements: Pakistan. Available at: https://www.imf.org/external/np/fin/tad/extarr2.aspx?memberKey1=760&date1key=2018-10-31

22IMF. (2018). Sri Lanka: Outstanding Purchases and Loans. Available at: https://www.imf.org/external/np/fin/tad/extcredt1.aspx?memberKey1=895&date1key=2018-09-30&roption=Y.

23IMF (2018). Article IV Consultation and Fourth Review under the Extended Arrangement under the Extended Fund Facility. IMF Country Report. Available at: https://www.imf.org/en/Publications/CR/Issues/2018/06/19/Sri-Lanka-2018-Article-IV-Consultation-and-the-Fourth-Review-Under-the-Extended-Arrangement-45997

24Ibid.

25IMF. (2018). Press Release: IMF Executive Board Approves Three-Year US.5 Billion Extended Arrangement under EFF for Sri Lanka. Available at: https://www.imf.org/en/News/Articles/2015/09/14/01/49/pr16262.

26IMF. (2018). Press Release: IMF Executive Board Approves Three-Year US.5 Billion Extended Arrangement under EFF for Sri Lanka. Available at: https://www.imf.org/en/News/Articles/2015/09/14/01/49/pr16262.

27IMF. (2018). Press Release: IMF Executive Board Approves Three-Year US.5 Billion Extended Arrangement under EFF for Sri Lanka. Available at: https://www.imf.org/en/News/Articles/2015/09/14/01/49/pr16262

28Recent Economic Developments. (2018). Colombo: CBSL, p.106. Available at: https://www.cbsl.gov.lk/sites/default/files/cbslweb_documents/publications/red/red_2016e.pdf#page=106

29IMF (2018). Article IV Consultation and Fourth Review under the Extended Arrangement under the Extended Fund Facility. IMF Country Report. Available at: https://www.imf.org/en/Publications/CR/Issues/2018/06/19/Sri-Lanka-2018-Article-IV-Consultation-and-the-Fourth-Review-Under-the-Extended-Arrangement-45997

30IMF. (2018). Press Release: IMF Executive Board Approves Three-Year US.5 Billion Extended Arrangement under EFF for Sri Lanka. Available at: https://www.imf.org/en/News/Articles/2015/09/14/01/49/pr16262.

31IMF. (2018). IMF Executive Board Concludes 2018 Article IV Consultation and Completes Fourth Review under the Extended Arrangement Under the Extended Fund Facility with Sri Lanka, Approving US$ 252 Million Disbursement. Available at: https://www.imf.org/en/News/Articles/2018/06/01/pr18212-sri-lanka-imf-executive-board-concludes-2018-article-iv-consultation.

32IMF. (2018). Article IV Consultation and Fourth Review under the Extended Arrangement under the Extended Fund Facility. IMF Country Report. Available at: https://www.imf.org/en/Publications/CR/Issues/2018/06/19/Sri-Lanka-2018-Article-IV-Consultation-and-the-Fourth-Review-Under-the-Extended-Arrangement-45997

33IMF. (2018). Sri Lanka: Projected Payments to the IMF as of September 30, 2018.Available at: https://www.imf.org/external/np/fin/tad/extforth.aspx?memberkey1=895&date1key=2018-09-30&category=forth&year=2018&trxtype=repchg&overforth=f&schedule=exp&extend=y.

[Adam Collins is a Research Fellow at the Lakshman Kadirgamar Institute of International Relations and Strategic Studies (LKI) in Colombo. Pabasara Kannangara is a Research Associate at LKI. The opinions expressed in this piece are the authors’ own and not the institutional views of LKI, and do not necessarily reflect the position of any other institution or individual with which the authors are affiliated. This LKI Explainer was originally published in November 2018, and was updated on February 2019.]