Tuesday Feb 17, 2026

Tuesday Feb 17, 2026

Tuesday, 25 June 2019 00:00 - - {{hitsCtrl.values.hits}}

At 19 years old, Sarah* has her whole life ahead of her. However, when asked about her biggest hope for the future, she cannot bring herself to picture it. She isn’t easily prone to hopelessness; a refugee from Pakistan, Sarah lived her entire life being discriminated against.

As Ahmadi Muslims, Sarah and her family were persecuted for their belief in the second coming of the Messiah. Although a peace-loving community, Ahmadi Muslims are rejected by majority sects in Pakistan.

“From the day I started school to the day we left Pakistan, we were persecuted. When I was small, the other children would refuse to play with me. They called us ‘Qadianis’ and wouldn’t even share water with me.”

But Sarah refused to let the hostility get in the way of her passion. A strong athlete, she played basketball, cricket, badminton, table tennis and more. On the courts or on the grounds, it didn’t matter what the others thought of her – the only things that mattered were her talent and her determination to succeed. She even represented her school at table tennis tournaments and basketball matches, playing in teams with the very students that isolated her. She has a few pictures of herself competing at various events saved on her phone that she displays with pride.

Her dreams of becoming a professional athlete came to a sudden halt when her family began to receive threats. Fearing for their safety, they had no choice but to flee the country. At 16, she left her life in Pakistan behind, along with everything and everyone she had ever known. But again, she wasn’t intimidated – her parents decided that Sri Lanka was the safest place for them to seek asylum, so she embraced her temporary stay here and was determined to enjoy it.

“Our experience in Sri Lanka was really awesome, we had a lot of fun and we had freedom. This was the most calm and safe place for us. My sisters and I could travel anywhere, even without our mother, and we felt free.”

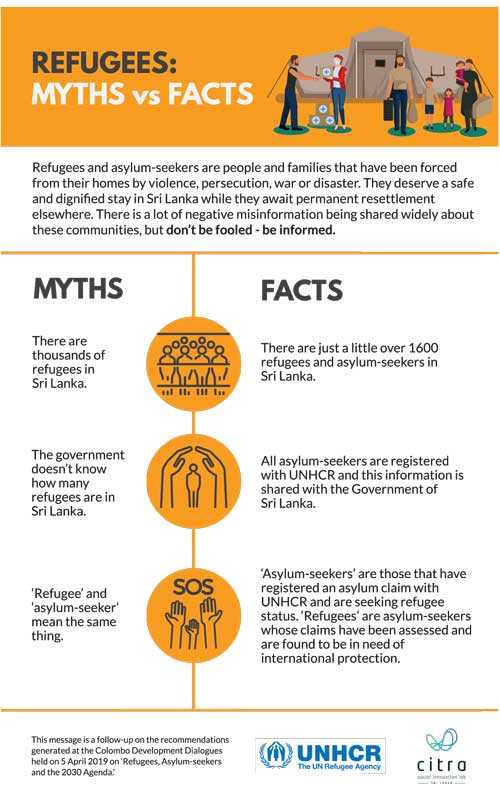

Sarah and her family spent two peaceful years in Sri Lanka. They registered their claim for asylum with UNHCR and rented a house after registering themselves at the local police station. They were awaiting resettlement in another country, as Sri Lanka does not permit refugees and asylum seekers to live in the country permanently. The Government allows families to remain in Sri Lanka until they are resettled in another country by UNHCR. The average refugee stays in Sri Lanka for three to seven years until they are permanently moved to a country that accepts refugees for resettlement.

Three days after the Easter Sunday attacks however, everything changed for Sarah and her family once again. Strange men came into their home and demanded that they get out, threatening to kill them if they didn’t do as they were told. They were given two hours to pack their belongings and leave the area. Sarah and her family fled to a relative’s house and stayed in hiding, but another group of strangers came into that house as well. Armed with sticks and knives this time, they wanted the same thing – they wanted them gone.

“We didn’t have anywhere else to go, so we came here (refugee shelter) and there were so many people here. We had just one hall for hundreds of people, sleeping and living in one hall. We were extremely tense, not sure what would happen to us.”

The uncertainty of their future is especially hard for Sarah; she doesn’t understand why this is happening to them.

“Till now we are hopeless, we don’t know what will happen next. I urge people to realise that we are not bad people. We haven’t done anything wrong. We are also sorry for the Easter attack and are in pain because of it. We spent two years in Sri Lanka and treated everyone like our brothers and sisters, so it was painful to us as well that so many lives were taken. But it wasn’t our fault, so why are we being punished?”

The stories are a follow-up on the recommendations generated at the Colombo Development Dialogues held on 5 April 2019 on ‘Refugees, Asylum-seekers and the 2030 Agenda’.

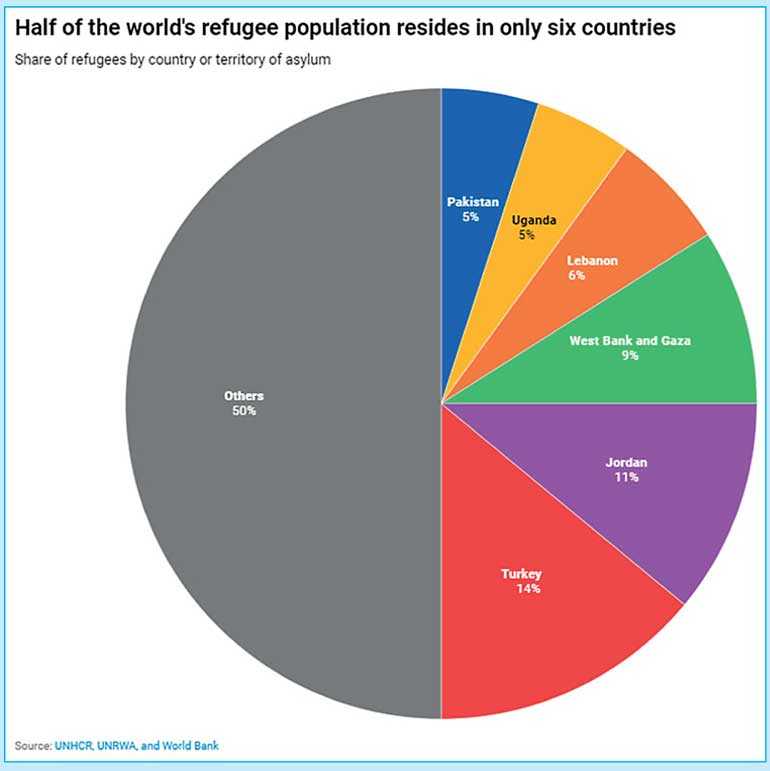

blogs.worldbank.org: The number of refugees globally rose to 25.9 million in 2018, up from 25.4 million in 2017, and setting a new record, according to newly released UNHCR report and World Bank estimates. The number of people seeking international protection outside of their country of origin has increased 70% since 2011.

Countries producing the largest numbers of refugees include (in order) the Syrian Arab Republic, Afghanistan, South Sudan, Myanmar, Somalia, and Sudan. More than half (56%) of the world’s refugees in 2018 came from these six countries. The number of refugees from Syria, South Sudan, and Myanmar has increased rapidly over the last couple of years.

Where do these refugees go? The majority of them live in countries neighbouring their countries of origin. About half of the world’s 26 million refugees are hosted by just six countries – Turkey, Jordan, West Bank and Gaza, Lebanon, Pakistan, and Uganda. The share rises to nearly 75% if the next eight refugee-hosting countries: Bangladesh, Chad, Congo DR, Ethiopia, Germany, Iran, South Sudan, and Syria. Among the regions of the world, the Middle East and North Africa, Sub-Saharan Africa, Europe and Central Asia, and South Asia host the largest numbers of refugees. The majority of hosts are low- and middle-income countries.

These new data will become available soon in the World Development Indicators database. To monitor these situations, statistics are critical to inform the response of the international community. The Expert Group on Refugee and Internally Displaced Persons Statistics (EGRIS) was established in 2016 and continues its efforts for more reliable and high-quality refugee statistics. (Source: https://blogs.worldbank.org/opendata/newly-released-data-show-refugee-numbers-record-levels?cid=ECR_E_NewsletterWeekly_EN_EXT&deliveryName=DM14839)