Thursday Feb 19, 2026

Thursday Feb 19, 2026

Friday, 18 May 2018 00:00 - - {{hitsCtrl.values.hits}}

By Meghal Perera

By Meghal Perera

In 2013, Army Commander General Jagath Jayasuriya spoke on the new challenge of transforming the Army from a wartime force to a peacetime force. Profit-making ventures that harnessed the manpower and resource capacity of the Army would power this transition, as “We can perform on a competitive basis because we are effective and efficient, so we can provide a good service. The Army is involved in almost all the services and professions that one can offer.”

Nearly five years since his interview, his words ring true. The armed forces have become increasingly profit-oriented, running beauty salons, luxury hotels, banquet halls, farms and wayside shops. While the Sri Lankan military is not quite the economic powerhouse when compared to Pakistan and Bangladesh, where the armed forces occupy a conglomerate-style grip over economies, increasing economic activity and revenue generation is a cause for concern.

Sri Lanka is not alone in framing military engagement in the economy as an alternative to demobilisation. In China, the People’s Liberation Army (PLA) initiated a period of intense economic activities during the 1980s, in response to a slimming defence budget and the need to resettle thousands of now-redundant troops. Buoyed by access to State-subsidised materials, tax exemptions, fast-tracked bureaucratic processes and the intangible perks associated with the armed forces, the PLA ran a sprawling commercial empire, associated with every imaginable good and service, from ice cream parlours to vehicle repair to pharmaceutical products.

A recent report entitled ‘Power and Profit: Investigating Sri Lanka’s Military Businesses’ by the South Asian Centre for Legal Studies (SACLS) shows how the armed forces use similar advantages to gain a competitive edge that distorts markets and hinders employment.

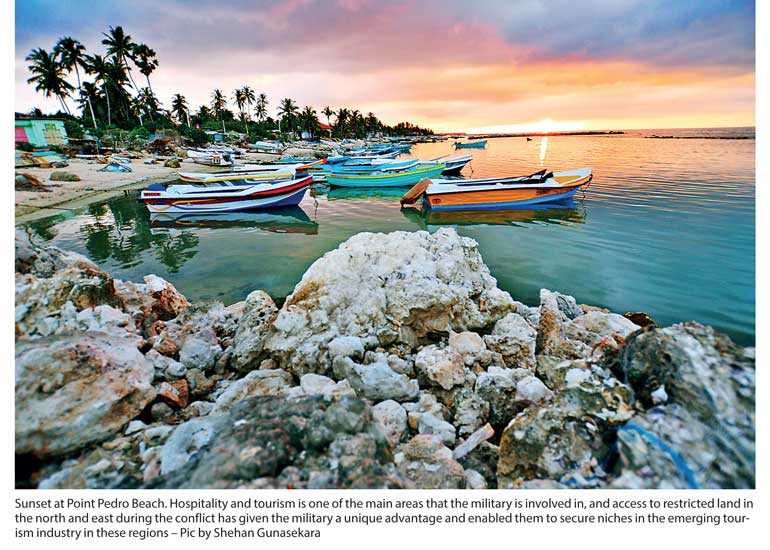

Hospitality and tourism is one of the main areas that the military is involved in, and access to restricted land in the north and east during the conflict has given the military a unique advantage and enabled them to secure niches in the emerging tourism industry in these regions.

Marble Beach in Trincomalee was occupied by the Air Force during the war, and although it was opened to the public post-conflict, a large stretch of beach remains exclusively for patrons of the Marble Beach Air Force Resort, a luxury hotel run and staffed solely by the Air Force. No private hotelier would be able to gain the access to attractive untouched property, let alone cordon off beaches and thus offer the appeal of seclusion and privacy to guests.

The Thalsevana Holiday Resort which is managed by the Sri Lanka Army also holds a similar monopoly over the Kankesanthurai beach, and the Malima Hospitality Services operated by the Sri Lanka Navy owns luxury hotels that reportedly lie on the private lands of evicted citizens.

These enterprises benefit from more than unrestricted geographic access. They make use of military equipment and resources – military vessels were initially used to conduct whale watching tours – and thus eliminate the capital-heavy expenditure that any aspiring entrepreneur must make. More importantly, as these ventures are staffed entirely by military personnel who are pay-rolled under defence budget allocations, these businesses are free from the financial shackles of cash flow and capital costs that all ordinary businesses are bound by. Given this massive reduction in operating costs, it is no wonder that military businesses have a razor-sharp competitive edge.

The SACLS findings report that whale watching tours operated by the Navy are half the price of their competitors, and the same advantage is held by the Air Force-run Helitours. While military ventures are providing the identical services as their civilian counterparts, their prices result in unfair competition, crowding out the market for future investors who cannot surmount these barriers to entry. These distorted market conditions have an adverse impact on local entrepreneurs and businesses, particularly in the north and east where many look towards tourism as a means of bringing in much-needed revenue to drive socio-economic development.

The Civil Security Department, initially known as the National Home Guard, has a prolific business presence in the Northern Province, where it actively recruits employees to work its agricultural farms and manufacturing projects. Its business model seems to work; CSD profits grew by 200% between 2014 and 2016. Most of these profits come from agricultural produce, which is sold in local markets usually at Rs. 10-14 cheaper, undercutting local farmers who already face obstacles of soil productivity and drought. Unable to compete with CSD prices, many farmers are faced with a choice; abandon this livelihood, or join the militarised CSD farms.

The booming profit margins of the CSD raise some questions. Can the supplementary force’s gazetted mandate of “protecting law and order” and “assisting with social welfare functions” be stretched to justify its new function as a chain of successful revenue-generating enterprises? The murkiness of the ownership and operating details of these military enterprises is unsurprising, given that they do not function as public corporations.

Legislature has not prohibited the military from engaging in economic activities, and the same allowances made for flexible internal administration, now enable these enterprises to be run at the complete discretion of senior officers. Free from internal procedures and audits, there is no method of accounting for the profits gained from these enterprises. While the armed forces state their annual revenue under the performance reviews, they do not need to declare the sources of specific income streams.

Underreporting of profits and abuse of funds by military personnel is a well-documented phenomenon in military businesses. During the height of the PLA’s economic expansion, Chinese authorities struggled to regulate the economic behemoth that the military had become. The extra-legal status protected it from civilian law enforcement. Profits were siphoned off to offshore bank accounts and military economic activity is even credited with cementing large scale embezzlement, fraud, bribery and nepotism into the economic fabric of the country.

It does not take a leap of imagination to imagine these off-book activities being replicated in Sri Lanka, given the lack of accountability of armed forces coupled with a culture of corruption. Just as official reporting of the PLA’s economic abuses was censored from 1993, to protect its reputation, abuse of funds may be ignored considering the revered attitudes towards the armed forces in Sri Lanka.

However, China’s eventual reversal of policy on military enterprise was not due to economic misuse or corruption. The cleaning-up and divesture from commercial activities at the order of Jiang Zemin was successful because it had the support of both civilian and military authorities, who had seen the detrimental effects that the pursuit of profit had had on the military structure and efficacy. Professionalism and combat readiness of the forces had been completely eroded, as they neglected their duties as soldiers. With changing relations with Taiwan signalling new security priorities, the PLA could no longer afford to devote its attention to commercial activities that hinder its cohesiveness and efficiency.

In Bangladesh, which mimics Pakistan’s military business model, numerous violations of sea and airspace by Myanmar have cast doubt on the capacity of the military to protect territorial sovereignty. Off-budget military spending finances the array of businesses rather than national defence, and the tension between these two objectives does not make for a unified disciplined fighting force. The 2009 Bangladesh Rifles mutiny was instigated by rank-and-file soldiers protesting the embezzlement by officers providing groceries to low income groups.

As modern warfare abandons boots-on-the-ground assaults and moves towards smaller specialised forces and the tech frontiers like cyber warfare, the relevance of Sri Lanka’s populous military needs to be re-examined. Its function in a post-conflict context needs re-evaluation as well.

The likelihood of invasion, given India’s overbearing presence in the Indian Ocean, the role of the Police in mitigating internal unrest, and the merit of absorbing discontented youth in the south are all questions that must be weighed. But any strategy and vision for national security will not benefit from the military’s continued participation in the commercial sphere.

Approving the pursuit of profit enables the creep of the military into civilian, which has the potential to reconfigure the precarious relationship between Government and the armed forces for the worse, as evinced in Pakistan. Innocuous though banquet halls and whale-watching tours may seem, military engagement disempowers communities and affects local economies. Is the net benefit to the public really the optimal use of tax-payers money, given that regulated Government entities involved in tourism and agriculture already exist? The military’s role in Sri Lanka today is fluid and undefined. But perhaps it is time to stop subsidising its identity crisis.